Review: DARKER BLUES – DAVID RACCUGLIA

SLUGmag

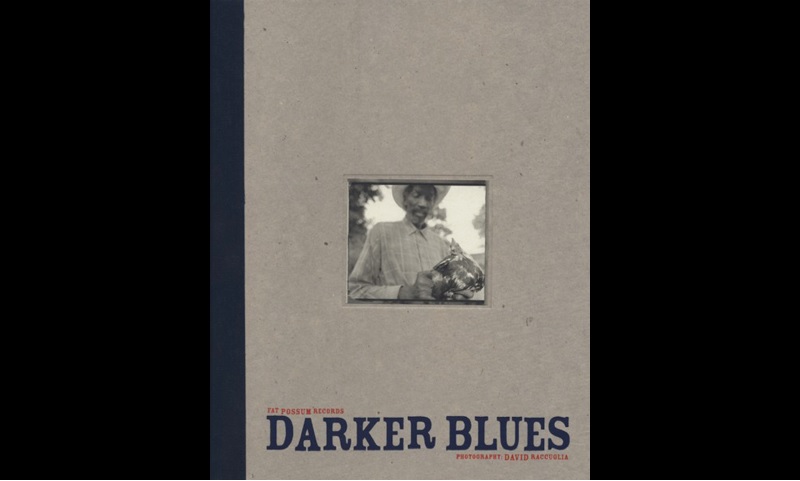

DARKER BLUES

DAVID RACCUGLIA

Fat Possum Records

Street: 02.01.03

Fat Possum’s motto is “We’re trying our best,” and I’d say their best is damn good enough. This is a beautifully papered, beautifully bound book with artsy, full-color photographs of the Fat Possum roster of Mississippi’s second generation of original bluesmen with a two-disc label sampler offering in the back. Fat Possum pursue their calling in the music world with a fervor and reverence akin to prophetic, anthropologic devotion. However, Matthew Johnson, who started Fat Possum with a student loan, balks at being called a “folklorist.” He says, “All we care about is capturing that vitality, the subversive intensity of our artists which are relevant in today’s world. I didn’t discover anybody, I just record blues guys who were overlooked by other labels because they hadn’t toured, or had limited repertoires, or were unreliable, or refused to play standing up. Guys who sometimes have trouble standing up, yet excel at falling down. But that’s the blues. At least what I call the blues.”

From classics like the late R.L. Burnside to more modern artists like Bob Log III and 20 Miles, Darker Blues delves into the backgrounds, musical inspirations and individual journeys that made these 16 men what they are: great, but not always acknowledged or revered, musicians. In fact, many haven’t ventured more than a few miles from their birthplace. Asie Payton lived in a small town in Mississippi called Holly Ridge and played almost every Saturday at one of the town’s two grocery stores. Fat Possum only succeeded in convincing Payton to record twice before he passed away; one of which is the playful, rhythmic “Do Me Right” that appears on the sampler. Scott Dunbar also never traveled more than 100 miles from where he was born and kept time while he played with a stomping boot heel, captured in his track “Easy Rider.”

Having the CD to listen to as you’re reading along is invaluable, bringing to life the sounds and style of each blues artist, and the variety and distinctness of each artist is amazing. The tracks I liked best were R.L. Burnside’s Boogie Intro remix (the second CD is exclusively R.L. Burnside material), Cedell Davis’ low, naked guitar ruled by bizarre, creative rhythms (played with a knife handle in his right hand and plucking left-handed because a severe case of polio affected his hands), Johnny Farmer’s track and Paul Jones’ sexy, slinky wah-wah electric number.

Most of the artist’s stories leave no wonder that they turned to the blues in order to cope with heartbreak, disappointment and outright tragedy. T-Model Ford’s story is of course one of the most publicized; serving two years on a chain gang for murder, among other troubles. Most of the artists have lived in extreme poverty most of their lives, worked the land and worked it hard. Most of them have families to support and do blues on the side as a passionate hobby, making little to no money at it.

My favorite two parts of the book that really capture the spirit of the blues to me is first, a picture of R.L. Burnside within the book’s few first pages. It’s black and white and he’s staring piercingly, almost suspiciously at the camera, his pupils rimmed with blue from age. He looks like a mythical creature that captures the universal consciousness of what it means to be mortal, and more specifically, oppressed. Second, the name of one of Junior Kimbrough’s album titles: “Most Things Haven’t Worked Out.” That, my friend, is the blues. –Rebecca Vernon