The Speedway Project: The History Within the Walls of SLC’s Legendary Underground Venue

Music Interviews

From 1986 to 1990, The Speedway Café was a magnet for underground music, housing both local and touring acts in a space that contributed heavily to the growth of SLC’s alternative community. After Speedway closed its doors 25 years ago, it left behind an imprint of something that a city like SLC needed in that time—an all-you-can-eat musical buffet that a starving, growing underground scene had been longing for previously. Documentarian Trinity West has set out to gather as many stories, fliers, ticket stubs, pictures and footage from anyone who was part of the venue’s history to make what will be both a documentary film and book.

While West hadn’t attended any Speedway shows due to her living in Price, Utah, for most of her childhood, she would hear about them from her brother, who went to shows religiously and would have their mother drive them to Raunch Records to obtain fliers as souvenirs. West says that it bonded her family in a weird way, and with this project, Speedway is still very much a family affair. “My mom watches my two boys while I’ve been researching and conducting interviews during our trips to SLC; my brother and little cousin have been working with me, and my husband, Justin Wambolt-Reynolds, is art directing everything with me as well as designing the ad,” says West. After going through some old fliers and discovering beautiful images of some fundamental bands taken by photographers Steve Midgley and Trent Nelson and hearing different stories about the venue, West realized that Speedway had a unique story to be told. She garnered moral support from SLUG Magazine Editor Angela Brown, Speedway owner Paul Maritsas and Brad Collins of Raunch Records. After mapping out her approach and the timeline, the project went public in November 2015.

West conceived of the book as a collective journal, compiling multiple perspectives to make it as authentic as possible. “That’s why I’m asking for any memorabilia or even written accounts and interviews,” she says. “It’s essential to have it told in each person’s own words.” The list of contributors includes local bands such as The Stench, Bad Yodelers, Insight, Boxcar Kids, Iceburn and Massacre Guys, who, prior to Speedway, didn’t have a venue to play in; national acts such as Soundgarden and Social Distortion, who became house bands from playing there so many times; and bands who played standout shows such as Ministry, who played to a crowd that was double the venue’s capacity.

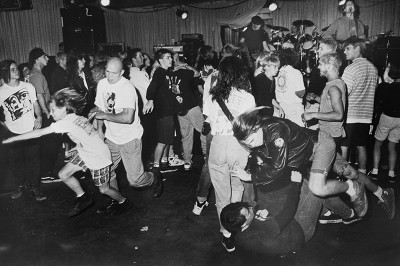

The idea for a documentary didn’t come to fruition until Maritsas suggested to West that she film him opening his boxes of Speedway memorabilia for the first time since it closed. “My background is not in film,” West says, “but as I was filming him going over the fliers of all the different bands, my mind was blown. That’s when I realized that there was a film here.” The film will focus on the underground scene of the Speedway colliding with the backdrop of SLC’s religious conservatism during the Ronald Reagan presidency. Since not enough video footage of Speedway exists, West reached out to Pushead—illustrator of Zorlac Skateboards and Raunch Records’ logo—to design illustrations for what will be animated portrayals of what went on behind the walls of the venue. “It gives the film some texture and more of a style, and when you don’t have enough material, you have to get creative,” says West. “The images and illustrations will give a sense of what it was like to be in the pit.”

Speedway first opened in 1984—cultivated as a local space for underground music, its catchphrase was “a café that served no food and had a bar that didn’t serve booze.” “There was a ground swell of musicians who were finding their community through it,” says West. When a band would be booked, local bands were always put on the bill since they had a bigger draw than the headliner. There were no musical limitations either—genres ranged from punk, metal, glam, rap and reggae. Maritsas would pitch to touring bands that they had an audience in SLC, which is the only major city between Reno and Denver. While there were a few other venues that accommodated the local scene, Speedway was the proverbial Mecca, just spitting distance from Raunch Records where people could congregate and discover new music.

Due to a lack of funding, Speedway officially closed its doors in 1990. West explains that Maritsas had a day job to support the venue, and Speedway was lucky to break even most nights. The venue was gone, but the community and the bands had gotten bigger—The Speedway Café became Speedway Productions and began to book them at bigger venues. Speedway was just one of the seeds that kept the scene thriving—SLUG Magazine, which was conceived within the walls of Speedway, became the resource for the scene to find out about different shows. Most shows would be played at venues like DV8 or the Zephyr but didn’t always cater to the underground demographic.

Each generation may have had their own version of it, but Speedway was a trailblazing institution that is still held in the highest light. West reestablishes that the purpose of this project is to capture and preserve the memories for future generations who have a flare for the history of underground music. With her up-close-and-personal approach, people will hear from firsthand accounts why Speedway Café is a countercultural treasure. To share your Speedway Café narrative, email West at trinity@speedwayproject.com.