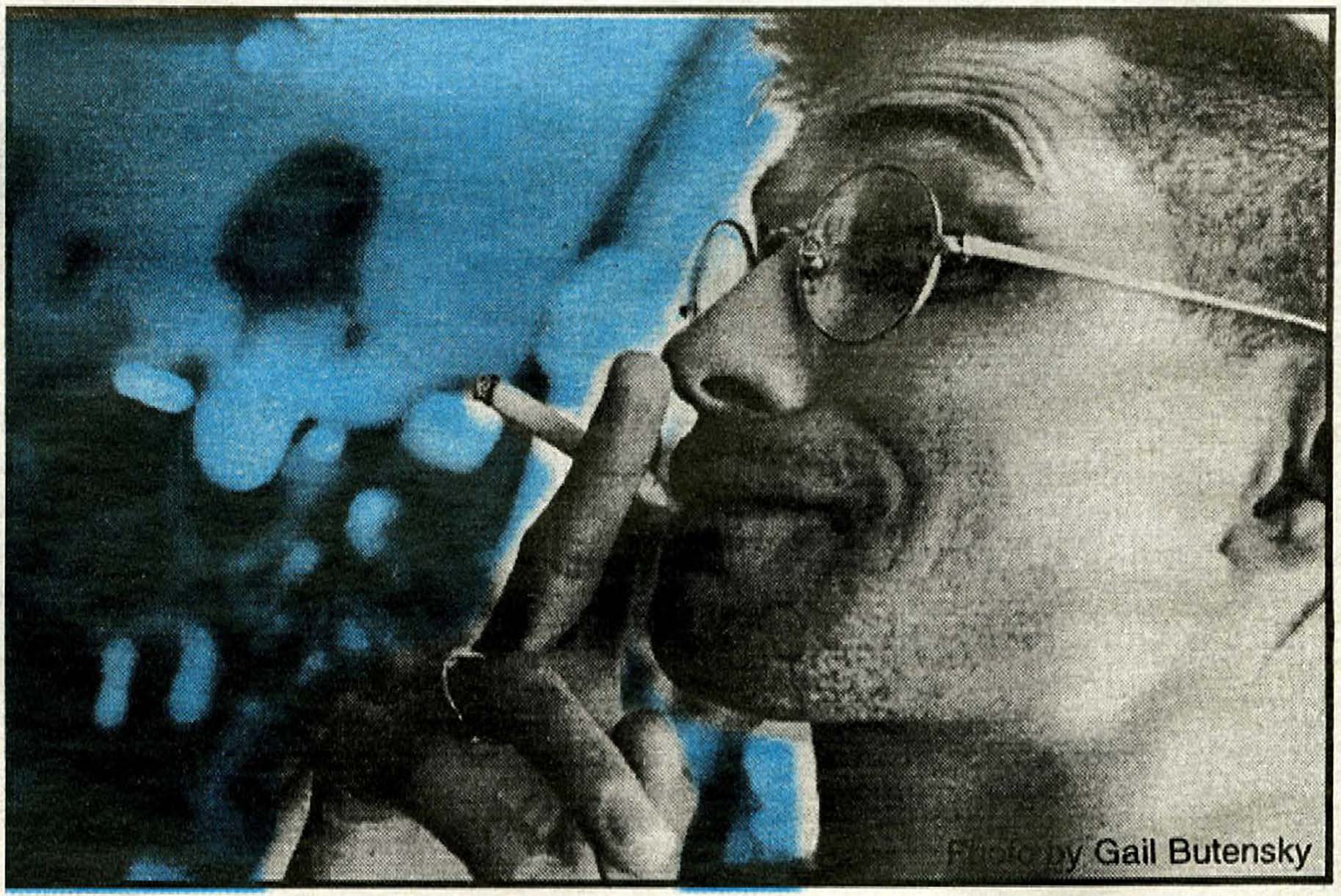

Questioning the Corporate Culture with Steve Albini

Archived

I’m not going to waste your time with some big introduction for Steve Albini. He is a producer and a musician. You have probably heard some of the albums he’s recorded. Two of my Albini-recorded favorites are the Pixies‘ Surfer Rosa and Nirvana‘s In Utero. His band Shellac is one of the best bands you’ve never heard, and he likes it that way. Find his music and appreciate it. This is the key to being a genuine fan as opposed to a follower of pop-culture-dictated trends. He has written one of the most critical and honest articles about the music business I have ever read, titled The Problem With Music, originally printed in MAXIMUMROCKNROLL in 1998 (an excerpt is reprinted here, below this interview). He has strong opinions, so we here at SLUG would like you to have the opportunity to enjoy them. If they happen to spark a revelation, you may become a super-ethical indie legend—just don’t forget from whence your inspiration came.

SLUG: First, some questions about Shellac. With this band, why have you generally scorned promotion and advertising?

Albini: It’s not so much a stance that the band is taking, it’s more that we do not want to be a part of the aggressive promotion of bands and personalities. It seems like whenever a band puts out a record, it is immediately thrust in front of you. This intrusion into all of our lives stems from people trying to sell ‘things’ not only records, but ‘things’ of all kinds. It seems like people are constantly trying to direct your attention toward something, and we’ve all occasionally felt like that is invasive and irritating. For our own peace of mind, we don’t want to be a part of that. We would rather accept the fact that we reach fewer people and sell fewer records. We feel good about not intruding upon people the way that aggressive promotion intrudes upon our lives all the time.

SLUG: How does the Touch and Go label feel about the way you do things?

Albini: Philosophically, Touch and Go as a record label and Shellac as a band are like two peas in a pod. Corey Rusk founded this record label as part of the punk rock/hardcore underground, so in those circumstances and in that medium, nobody really wanted to be a part of the mainstream culture. Everyone sort of accepted that we were outside of that, so the record label has absolutely no problem with us not promoting the records or the band. In fact, it makes life very easy for them. When they have a million things to do in terms of promoting a band, getting a record out, getting a review solicited or all that sort of thing, they just take us off the list and don’t worry about us. It frees up a lot of their time and energy for bands that want to be more actively promoted. I feel good about that. I feel like instead of being this band that takes up all the time and energy of the record label’s staff, we make their lives easier. It carries through, not just from the promotion aspect, but in other areas like manufacturing and production. We don’t ever expect a specific release date [and] we don’t tour commensurate with the timing of the record release, so we don’t have an agenda that forces people to work late. I don’t begrudge anybody else for thinking another way. I mean, there’s the perspective that if you’re doing something with a band that you want as many people to hear it as possible. I don’t hold that perspective, but I can understand it and I don’t begrudge anyone else for feeling that way.

SLUG: There are very few bands that actually do that. On a mainstream level, what do you think about the members of a band like Tool who minimize their appearance and personality to maintain a certain amount of focus on their music?

Albini: Well, I can’t speak for them, but my perception of Tool is that they’re just like every other band. I don’t actually consider anything they do as being dramatically different from anybody else. I realize that we’re talking about shades of gray, and so possibly, from their perspective, perhaps they’re doing something that’s very selfless and very unabsorbed. I don’t know, maybe they are making some sort of a stand in the circles that they travel. It’s just that from my perspective as an outsider, they seem to be just like any other band.

SLUG: And they still cash a big paycheck at the end of the day…

Albini: I have absolutely no qualms about a band making money. I think a band making money [off of] what they do is the most fantastic and rare situation there is. If a band is making money by being a band, then god bless ’em, they’re the one in a million. I have no reservations about a band making money.

SLUG: Well, I didn’t mean it offensively.

Albini: I know, but all the bands that I admire, like Crass, the X or Fugazi, all these bands make money doing what they’re doing, and that’s testament to the way that they do things. You can do things in a non-exploitative way. You can do things in a non-selfish or non-‘industry-standard’ manner and still make it. You can make up your own rules and by conducting yourself honorably, you can still make money. It’s a pervasive argument for people that do things in the exploitative ‘industry-standard’ fashion and who say, “Well, we want to make a living at it, and we want to make money, so we have to do this … ” Bands like Shellac, Fugazi, the X and all these other bands that don’t operate that way prove that you don’t need to do things the standard way to make money. Shellac makes loads of money. We’re non-exploitative in that we don’t take advantage of our position and that we don’t try to take advantage of our fans or our record label. We don’t try to “work the system” the way we could if we only wanted to siphon out money. We make money by operating efficiently, not over spending on anything and by being reasonable and rational about all of our decisions. I think that making money is kind of a convenient excuse for this sort of ‘rock star’ type behavior, and it really isn’t a valid excuse.

SLUG: How relevant is your 1998 MMR article, The Problem with Music in the year 2000? Do you think the music industry has changed its tactics for seducing and exploiting new talent very much since then?

Albini: Well, within the mainstream music business and in regard to record labels that sign artists to contracts for an extended period of time, I think that things have gotten worse. Especially in terms of the band’s proportional payment—things have gotten dramatically worse. Record royalty base rates have fallen dramatically. The total number of exclusions in contracts has increased, the percentage of payments has decreased and accounting periods have lengthened. All of those marginal things have gotten worse for bands in the mainstream world. In the independent sphere, outside the mainstream, things have stayed basically the same or gotten easier. The internet provides an easier means of promotion and sales for independent bands and labels. The internet lowers things like office costs by keeping telephone usage down and that makes it easier. The fact that the mainstream music business now is almost exclusively selling records that none of us care about means that there is no crossover. Independent bands and labels now have absolutely no reason to advertise in publications like Rolling Stone, SPIN or those skateboarding magazines. There is still an underground and there is still a mainstream, just the way there has been for the twenty years previous to this ‘alternative’ rock era.

SLUG: How do you feel about labels that may promote themselves or their image as ‘independent’ while having major label backing?

Albini: I don’t think the labels promote themselves. They try to create an image that is based on a few tangibles, like the way that their ads appear, the types of gigs that the bands play or the way that they’re promoted. Labels can’t do interviews … (Laughs).

SLUG: What do you think of bands that try to ‘shop’ themselves out to record labels? Do you think this is a productive way of doing things or should they just concentrate on doing things for themselves and see what comes of it?

Albini: That’s a mentality that you either have or you don’t. The people that have that mentality will behave that way regardless of what happens, and people who don’t will never be convinced. I don’t know if that mentality is even worth debating because the results are so evident. Either the members of a band go through the effort of trying to make themselves popular and desirable or they don’t. The net result is how you evaluate it. In some instances, obviously, a band wouldn’t have ‘shopped themselves out’ if they didn’t have that mentality or that self-promotional streak. They wouldn’t do anything. But in some instances, I think it’s an unnecessary bit of baggage for the band.

SLUG: How can a band circumvent that and get themselves to a larger audience?

Albini: Well, the question that you’re asking presupposes that the band wants to get to a bigger audience. I think that’s the fundamental difference. There are some people that play music for its own sake, so an audience, if there is one, will gravitate towards them of its own attraction. If you put flypaper down, flies will eventually stick to it, you know? If you make a flyswatter, maybe you’ll get a few more flies. I feel like if the band’s members are making their music for their own entertainment, and to please themselves, then at least they will get that much enjoyment out of it. If other people discover them through word of mouth or stumble across their music, then those people will genuinely appreciate the band. That’s the band’s natural audience. Whereas, if this band is thrust in front of people who may or may not give a damn about them, then whatever opinions those people form will not necessarily be closely held. These people won’t become dedicated, sincere fans. These people might be momentarily interested in the band and they might be tricked into buying a record or a T-shirt, but l don’t think that is any way to build a natural fan base.

SLUG: It’s more like a pop-cultural gravitation.

Albini: Yeah. Look at the bands that have survived. I don’t mean for two years, I mean for twenty years. Bands that have developed a rabid following, a hardcore following. Those bands are, generally speaking, not the bands that have gone out of their way to promote themselves. Those are the bands that do what they do exclusively for their own tastes, to please themselves. The genuine nature of their music is what attracted dedicated fans.

SLUG: Like The Jesus Lizard—I think that they have a rabid following based upon the shows and music rather than any image of the band.

Albini: Right, so using that band as an example, they went through a period where they were trying to promote themselves to an ‘outsider ‘ audience, an audience outside their natural fan base. They did these tours like Lollapalooza, or opening for Rage Against the Machine, Ministry and Bush, and thrust themselves in front of an audience that wouldn’t necessarily appreciate them. I don’t think that their core fan base increased at all because of that effort. It was a much more inefficient means of working, I think that led to a sense of dissatisfaction within the band, so ultimately the band had to stop. I don’t think that their natural following changed through this very aggressive effort to promote themselves to a different audience. That is an example of a band that still has a base of dedicated fans despite the band’s unproductive efforts to promote themselves to a mainstream audience.

SLUG: What do you think of bands that seem to be produced to attract the mainstream audience? Take Blink-182 as an example, they started out independent, then signed with a major label and now are one of the bands that are most aggressively promoted to the mainstream audience. This creates a whole sub-genre that emulates their sound. Now there are at least ten rip-offs of that ‘pop punk’ thing that had been done for years, but wasn’t commercially viable.

Albini: I can’t specifically write off any band. I know, for example, that the members of Blink were together long before they signed with a big record label. They were a band and they were putting out records independently, so I can’t second-guess their motives. There are bands that have been put together specifically to sound like Blink. There have been bands that are comprised of people who have been kicking around in five or six different bands over the years that used to sound like Nirvana, then they sounded like Pearl Jam, then they sounded like Korn and now they’re sounding like Third Eye Blind or whatever. There are bands that adopt these personas one after another until somebody buys it and at face value it seems to be the most insincere approach imaginable. I can’t name any one band and say that they’re insincere and phony, because I don’t know what their motives are. I think Blink might very well be genuine about what they’re doing. They certainly haven’t done what, for example, Sugar Ray did, where they changed from being a straight up pop-punk rock band to being a dance pop band with Latin and hiphop undertones. That’s a complete paradigm shift within that band and it makes the listener curious as to why that shift occurred, but even in that situation I can’t say with certainty that they’re being phony because maybe their tastes just changed. I don’t know.

SLUG: What is the biggest factor that determines which bands you work with in your recording studio?

Albini: I basically try not to say, “No.” If a band approaches me and they’re genuine about wanting to do a record, it’s not a political move on their record label’s part to get me involved and I think I can do a good job, then I’ll do it. I keep in mind the style, people and motivation behind the music. The amount of money that I get paid doesn’t matter at all. It doesn’t even enter into the discussion.

SLUG: Do you use some of the money that you earn from your larger projects to kind of ‘filter’ down so that you can record bands that might not be able to afford production costs?

Albini: A lot of people make that assertion, but I don’t. Not consciously, anyway. Some people have pictured me as some sort of a Robin Hood character, where I’m sort of screwing the big bands to pay for the little bands, but I honestly haven’t had that motivation enter my mind. In all honesty, I approach each thing that I do of its own nature as an individual event. If a band approaches me about doing their record, I’ll do it if I feel like I can do it and I feel like everyone is being genuine about the request, then I’ll do it. If a band approaches me and I smell a rat somewhere, you know, if I feel like the reason they want to do it isn’t genuine, then I’ll probably decline. Seriously, that’s the only criterion. There really isn’t some sort of Robin Hood mentality in play at all. If a record is so stylistically or conceptually out of my range of experience, then I won’t do it. If a band approached me to do a dance-pop album or a boy band or one of those cute girl records, I wouldn’t have the slightest idea about how to do that stuff. I’ve never done anything like that. From a technical standpoint, I think I could pull it off, but why involve me? I don’t have any taste for that kind of music, so that sort of thing would be pointless.

SLUG: Do you produce a lot of your own albums?

Albini: All Shellac albums have been produced by the band itself. Bob [Weston] and I are both engineers, so the technical aspect of it is covered pretty well. The aesthetic angle comes from a sort of group mentality. Everyone has things to say and things that they want observed in this band. There really isn’t a ‘big cheese’, there really isn’t one boss.

SLUG: Was Bob an engineer prior to being in this band or has that come from working with you?

Albini: Yeah, Bob’s training is in electrical engineering; he used to be a radio engineer. He has worked in studio installation and things like that. He has been recording albums for years.

SLUG: As a musician, I find it difficult to juggle work and touring sometimes. Considering your expansive work schedule, has that problem affected your band at all?

Albini: I have to disagree. I had a straight job for years. From when I got out of college through about 1986, something like that, I had a full-time, 40 hour per week job. I had so much fucking free time it was unreal. I had weekends off. I had every evening free. I mean, every evening I could do whatever I wanted. I had holidays, oh boy, what a fantastic lifestyle that was. Yeah, having a job is great. There are times when I wish for the days when I had a job. Think about it—if your band has to pay your rent, then you will do anything to get by. The end of the month is coming, you don’t have any money, fuck it, play a wedding, you know? Learn “Proud Mary” and go play somebody’s wedding. You will whore yourself to an unbelievable degree just to pay rent. If you’re a professional musician and you don’t do anything else, then you’ve suddenly removed yourself from that notion that your music is not beholden to anything, because your music is instantly beholden to paying your rent.

SLUG: I’ve never thought of my having a full time job as being productive to my band’s agenda. I usually think the opposite, but…

Albini: That’s exactly the perspective that I take on it. I think that it frees the band up so dramatically. I mean, we don’t really have to care if anybody likes us or not. We’re not living off of the band, so if we put out a record and it stinks and nobody likes it, it doesn’t affect us at all. We’re not going to go hungry, you know? Any band that is in this situation never has the thought enter their mind, “Is this going to be popular?” or “Is this going to be successful?” because it doesn’t fucking matter.

SLUG: And it frees you up creatively to do whatever you want…

Albini: Yeah, the most important thing about being in a band is that you get to do whatever comes to mind. And if you have to worry about making rent, then you don’t have that luxury of doing whatever comes to mind. Literally, all you can do is make sure that you have enough money coming in. Suddenly, it becomes really important how much money you make at each gig. Suddenly, it becomes really important how many records you sell. That stuff directly affects your standard of living.

SLUG: Do you see any improvement in the ability to network on an underground level due to improved technology, i.e. the internet?

Albini: I have to say that, for me, it’s precisely the same as it’s always been. You find your own connections, you make your own contacts, and before long you have a phone book full of people that you can use reliably. The more times you pass through, the more things that you do, the easier it is.

SLUG: Have you passed through Salt Lake City before?

Albini: We’ve never played there. We don’t play the West Coast too much because the drive is so long and there’s not much between here and there.

SLUG: Well, hopefully we’ll see you here someday. Thanks for talking to me Steve, we’ll see you.

Albini: Sure. Bye. There you have it. Now, do me a favor and try to do something for your art. Being an apathetic slob isn’t going to cut it anymore…

A Cross-Section of the Steve Albini Discography

Alternative TV, The Amps, Ativin, The Auteurs, Bedhead, Bewitched, Big Black, The Big Boys, Bitch Magnet, Brainiac, The Breeders, Brise-Glace, Bush, Cheap Trick, Cheer-Accident, Chevelle, Chisel Drill Hammer, Cinerama, Chris Connelly, Tony Conrad, Cordelia’s Dad, Crain, Crow, Dazzling Killmen, Dianogah, Dirty Three, Dis, Don Caballero, Eclectics, 18th Dye, Ein Heit, The Ex, Faucet, Filibuster, The Fleshtones, Flogging Molly, Flour, The Frogs, Robbie Fulks, Gastr del Sol, Great Unraveling, Guided by Voices, P.J. Harvey, Helmet, Hosemobile, Jawbreaker, Killdozer & Ritual, Les Thugs, Lizard Music, P.W. Long’s Reelfoot, Low, Man Dingo, Man or Astroman?, Melt-Banana, A Minor Forest, Morsel, Naked Raygun, Neurosis, Nine Inch Nails, Nirvana, Will Oldham, Jimmy Page & Robert Plant, Palace Music, Pansy Division, Pegboy, Pezz, Phoenix Thunderstone, Pigface, The Pixies, Plush, Poster Children, Rapeman, Rosa Mota, Sandy Duncan’s Eye, Fred Schneider, Scrawl, Screeching Weasel, Shellac, Silkworm, Silver Apples, Slint, Smog, Space Streakings, Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Spider Virus, Squirrel Bait, Steel Pole Bathtub, Storm & Stress, Tad, Tar, Teenage Frames, Tortoise, The Traitors, Union Carbide Productions, Union, In Terminus GA, Usherhouse, Ut, Uzeda, The Wedding Present, Shannon Wright, The Young Dubliners, Zeni Geva.

The above information is all taken from www.allmusic.com. Steve Albini is also set to produce The Breeders’ return CD in 2001.

MAXIMUMROCKNROLL #133

The Problem with Music

By Steve Albini

Excerpted from Baffler No. 5

Whenever I talk to a band who are about to sign with a major label, I always end up thinking of them in a particular context. I imagine a trench, about four feet wide and five feet deep, maybe sixty yards long, filled with runny, decaying shit. I imagine these people, some of them good friends, some of them barely acquaintances, at one end of this trench. I also imagine a faceless industry lackey at the other end, holding a fountain pen and a contract waiting to be signed.

Nobody can see what’s printed on the contract. It’s too far away, and besides, the shit stench is making everybody’s eyes water. The lackey shouts to everybody that the first one to swim the trench gets to sign the contract. Everybody dives in the trench and they struggle furiously to get to the other end. Two people arrive simultaneously and begin wrestling furiously, clawing each other and dunking each other under the shit. Eventually, one of them capitulates, and there’s only one contestant left. He reaches for the pen, but the Lackey says, “Actually, I think you need a little more development. Swim it again, please. Backstroke.”

And he does, of course.

I. A&R Scouts

Every major label involved in the hunt for new bands now has on staff a high-profile point man, an “A&R” rep who can present a comfortable face to any prospective band. The initials stand for “Artist and Repertoire,” because historically, the A&R staff would select artists to record music that they had also selected, out of an available pool of each. This is still the case, though not openly.

These guys are universally young (about the same age as the bands being wooed), and nowadays they always have some obvious underground rock credibility flag they can wave. Lyle Preslar, former guitarist for Minor Threat, is one of them. Terry Tolkin, former NY independent booking agent and assistant manager at Touch and Go is one of them. Al Smith, former soundman at CBGB is one of them. Mike Gitter, former editor of XXX fanzine and contributor to Rip, Kerrang and other lowbrow rags is one of them. Many of the annoying turds who used to staff college radio stations are in their ranks as well.

There are several reasons A&R scouts are always young. The explanation usually copped-to is that the scout will be “hip” to the current musical “scene.” A more important reason is that the bands will intuitively trust someone they think is a peer, and who speaks fondly of the same formative rock and roll experiences.

The A&R person is the first person to make contact with the band, and as such is the first person to promise them the moon. Who better to promise them the moon than an idealistic young turk who expects to be calling the shots in a few years, and who has had no previous experience with a big record company. Hell, he’s as naive as the band he’s duping. When he tells them no one will interfere in their creative process, he probably even believes it.

When he sits down with the band for the first time, over a plate of angel hair pasta, he can tell them with all sincerity that when they sign with company X, they’re really signing with him, and he’s on their side. Remember that great gig I saw you at in ’85? Didn’t we have a blast?

By now all rock bands are wise enough to be suspicious of music industry scum. There is a pervasive caricature in popular culture of a portly, middle aged ex-hipster talking a mile-a-minute, using outdated jargon and calling everybody “baby.” After meeting “their” A&R guy, the band will say to themselves and everyone else, “He’s not like a record company guy at all! He’s like one of us.” And they will be right. That’s one of the reasons he was hired.

These A&R guys are not allowed to write contracts. What they do is present the band with a letter of intent, or “deal memo,” which loosely states some terms, and affirms that the band will sign with the label once a contract has been agreed on.

The spookiest thing about this harmless sounding little “memo,” is that it is, for all legal purposes, a binding document. That is, once the band sign it, they are under obligation to conclude a deal with the label. If the label presents them with a contract that the band don’t want to sign, all the label has to do is wait. There are a hundred other bands willing to sign the exact same contract, so the label is in a position of strength.

These letters never have any term of expiration, so the band remain bound by the deal memo until a contract is signed, no matter how long that takes. The band cannot sign to another label or even put out its own material unless they are released from their agreement, which never happens. Make no mistake about it: once a band has signed a letter of intent, they will either eventually sign a contract that suits the label or they will be destroyed.

One of my favorite bands was held hostage for the better part of two years by a slick young “He’s not like a label guy at all,” A&R rep, on the basis of such a deal memo. He had failed to come through on any of his promises (something he did with similar effect to another well-known band), and so the band wanted out. Another label expressed interest, but when the A&R man was asked to release the band, he said he would need money or points, or possibly both, before he would consider it.

The new label was afraid the price would be too dear, and they said no thanks. On the cusp of making their signature album, an excellent band, humiliated, broke up from the stress and the many months of inactivity.

II. There’s This Band

There’s this band. They’re pretty ordinary, but they’re also pretty good, so they’ve attracted some attention. They’re signed to a moderate-sized “independent” label owned by a distribution company, and they have another two albums owed to the label.

They’re a little ambitious. They’d like to get signed by a major label so they can have some security—you know, get some good equipment, tour in a proper tour bus—nothing fancy, just a little reward for all the hard work.

To that end, they got a manager. He knows some of the label guys, and he can shop their next project to all the right people. He takes his cut, sure, but it’s only 15%, and if he can get them signed then it’s money well spent. Anyway, it doesn’t cost them anything if it doesn’t work. 15% of nothing isn’t much!

One day an A&R scout calls them, says he’s “been following them for a while now,” and when their manager mentioned them to him, it just “clicked.” Would they like to meet with him about the possibility of working out a deal with his label? Wow. Big Break time.

They meet the guy, and y’know what—he’s not what they expected from a label guy. He’s young and dresses pretty much like the band does. He knows all their favorite bands. He’s like one of them. He tells them he wants to go to bat for them, to try to get them everything they want. He says anything is possible with the right attitude. They conclude the evening by taking home a copy of a deal memo they wrote out and signed on the spot.

The A&R guy was full of great ideas, even talked about using a name producer. Butch Vig is out of the question—he wants 100 g’s and three points, but they can get Don Fleming for $30,000 plus three points. Even that’s a little steep, so maybe they’ll go with that guy who used to be in David Letterman’s band. He only wants three points. Or they can have just anybody record it (like Wharton Tiers, maybe—cost you 5 or 10 grand) and have Andy Wallace remix it for 4 grand a track plus 2 points. It was a lot to think about.

Well, they like this guy and they trust him. Besides, they already signed the deal memo. He must have been serious about wanting them to sign. They break the news to their current label, and the label manager says he wants them to succeed, so they have his blessing. He will need to be compensated, of course, for the remaining albums left on their contract, but he’ll work it out with the label himself. Sub Pop made millions from selling off Nirvana, and Twin Tone hasn’t done bad either: 50 grand for the Babes and 60 grand for the Poster Children—without having to sell a single additional record. It’ll be something modest. The new label doesn’t mind, so long as it’s recoupable out of royalties.

Well, they get the final contract, and it’s not quite what they expected. They figure it’s better to be safe than sorry and they turn it over to a lawyer—one who says he’s experienced in entertainment law—and he hammers out a few bugs. They’re still not sure about it, but the lawyer says he’s seen a lot of contracts, and theirs is pretty good. They’ll be getting a great royalty: 13% (less a 10% packaging deduction). Wasn’t it Buffalo Tom that were only getting 12% less 10?

Whatever. The old label only wants 50 grand, and no points. Hell, Sub Pop got 3 points when they let Nirvana go. They’re signed for four years, with options on each year, for a total of over a million dollars! That’s a lot of money in any man’s english. The first year’s advance alone is $250,000. Just think about it, a quarter-million, just for being in a rock band!

Their manager thinks it’s a great deal, especially the large advance. Besides, he knows a publishing company that will take the band on if they get signed, and even give them an advance of 20 grand, so they’ll be making that money too. The manager says publishing is pretty mysterious, and nobody really knows where all the money comes from, but the lawyer can look that contract over too. Hell, it’s free money.

Their booking agent is excited about the band signing to a major. He says they can maybe average $1,000 or $2,000 a night from now on. That’s enough to justify a five week tour, and with tour support, they can use a proper crew, buy some good equipment and even get a tour bus! Buses are pretty expensive, but if you figure in the price of a hotel room for everybody in the band and crew, they’re actually about the same cost. Some bands (like Therapy? and Sloan and Stereolab) use buses on their tours even when they’re getting paid only a couple hundred bucks a night, and this tour should earn at least a grand or two every night. It’ll be worth it. The band will be more comfortable and will play better.

The agent says a band on a major label can get a merchandising company to pay them an advance on t-shirt sales! Ridiculous! There’s a gold mine here! The lawyer should look over the merchandising contract, just to be safe.

They get drunk at the signing party. Polaroids are taken and everybody looks thrilled. The label picked them up in a limo. They decided to go with the producer who used to be in Letterman’s band. He had these technicians come in and tune the drums for them and tweak their amps and guitars. He had a guy bring in a slew of expensive old “vintage” microphones. Boy, were they “warm.” He even had a guy come in and check the phase of all the equipment in the control room! Boy, was he professional. He used a bunch of equipment on them and by the end of it, they all agreed that it sounded very “punchy,” yet “warm.”

All that hard work paid off. With the help of a video, the album went like hotcakes! They sold a quarter million copies!

Here is the math that will explain just how fucked they are:

These figures are representative of amounts that appear in record contracts daily. There’s no need to skew the figures to make the scenario look bad, since real-life examples more than abound. Income is underlined, expenses are not.

Advance: $250,000

Manager’s cut: $37,500

Legal fees: $10,000

Recording Budget: $150,000

Producer’s advance: $50,000

Studio fee: $52,500

Drum, Amp, Mic and Phase “Doctors”: $3,000

Recording tape: $8,000

Equipment rental: $5,000

Cartage and Transportation: $5,000

Lodgings while in studio: $10,000

Catering: $3,000

Mastering: $10,000

Tape copies, reference CD’s, shipping tapes, misc expenses: $2,000

Video budget: $30,000

Cameras: $8,000

Crew: $5,000

Processing and transfers: $3,000

Offline: $2,000

Online editing: $3,000

Catering: $1,000

Stage and construction: $3,000

Copies, couriers, transportation: $2,000

Director’s fee: $3,000

Promotional photo shoot and duplication: $2,000

Band fund: $15,000

New fancy professional drum kit: $5,000

New fancy professional guitars (2): $3,000

New fancy professional guitar amp rigs (2): $4,000

New fancy potato-shaped bass guitar: $1,000

New fancy rack of lights bass amp: $1,000

Rehearsal space rental: $500

Big blowout party for their friends: $500

Tour expense (5 weeks): $50,875

Bus: $25,000

Crew (3): $7,500

Food and per diems: $7,875

Fuel: $3,000

Consumable supplies: $3,500

Wardrobe: $1,000

Promotion: $3,000

Tour gross income: $50,000

Agent’s cut: $7,500

Manager’s cut: $7,500

Merchandising advance: $20,000

Manager’s cut: $3,000

Lawyer’s fee: $1,000

Publishing advance: $20,000

Manager’s cut: $3,000

Lawyer’s fee: $1,000

Record sales: 250,000 @ $12 = $3,000,000 gross retail revenue

Royalty (13% of 90% of retail): $351,000

Less advance: $250,000

Producer’s points: (3% less $50,000 advance) $40,000

Promotional budget: $25,000

Recoupable buyout from previous label: $50,000

Net royalty: (-$14,000)

Record company income:

Record wholesale price $6.50 x 250,000 = $1,625,000 gross income

Artist Royalties: $351,000

Deficit from royalties: $14,000

Manufacturing, packaging and distribution @ $2.20 per record: $550,000

Gross profit: $710,000

The Balance Sheet: This is how much each player got paid at the end of the game.

Record company: $710,000

Producer: $90,000

Manager: $51,000

Studio: $52,500

Previous label: $50,000

Agent: $7,500

Lawyer: $12,000

Band member net income each: $4,031.25

The band is now 1/4 of the way through its contract, has made the music industry more than 3 million dollars richer, but is in the hole $14,000 on royalties.

The band members have each earned about 1/3 as much as they would working at a 7-11, but they got to ride in a tour bus for a month.

The next album will be about the same, except that the record company will insist they spend more time and money on it. Since the previous one never “recouped,” the band will have no leverage, and will oblige.

The next tour will be about the same, except the merchandising advance will have already been paid, and the band, strangely enough, won’t have earned any royalties from their t-shirts yet. Maybe the t-shirt guys have figured out how to count money like record company guys.

Some of your friends are probably already this fucked.

Copyright 1994-2000 MAXIMUMROCKNROLL, majorlabels@rlabels.com.

Read more music interviews here:

Melvins Interview: April 1995

Band Interview: Smile