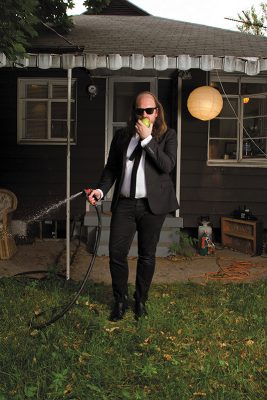

Localized: Matthew McMurray

Localized

It’s time for Localized to stage the city’s wire-fiddlers and underground electronic craftspeople. Matthew Fit’s low-key, dubbed house starts the night off, followed by the dance tracks of Matthew McMurray before exploding into SIAK’s driving, distorted techno tracks. Sponsored by Uinta Brewing, High West Distillery, KRCL 90.9 FM and Spilt Ink SLC, the free, 21-plus show at Urban Lounge takes place on Sept. 21 and will be a perfect night for anyone interested in exploring the city’s experimental dance scene.

Matthew McMurray doesn’t give many straight answers. Not because he comes off as elusive or aloof, but rather because he seems to be debating between two equally valid sides of an idea. Each question I ask him yields one answer shortly followed by a “but …” and an analysis of what benefits another option or path might yield.

For example, when asked about having diverse influences (head to matthewmcmurray.com to check out his eclectic DJ mixes), he responds with a few ideas. “There’s the side of ‘you like what you like,’ and you gravitate toward what speaks to you. So, there’s a very natural way of coming to find the sounds that you like,” he says, making it seems almost incidental that he places “Houses in Motion” right up against ’50s pop. He is, however, quick to retrace his steps. “Also, you’re the creative sum of your influences,” he says. “Having an eclectic mix and having something that spans a lot of seemingly disparate styles is important as a person. You should be well-rounded and you should have depth and breadth,” making these choices seem more intentional.

McMurray’s music tastes reflects these two differing theories. He comes across as someone who goes out of their way to find different and unique sounds, simply because he loves those sounds. Throughout our conversation, he talks extensively about St. Vincent, Ashra, Todd Rundgren, La Monte Young, draws comparisons between James Brown and Terry Riley, all while Latin vocal pop plays on his stereo. McMurray doesn’t talk about these differing and esoteric influences with an air of pretentiousness—instead, he comes off as excited and motivated by the greatest from all sorts of genres and styles.

Within this love of disparate styles of music is McMurray’s music itself. While his Localized show will feature dance-oriented music in order to keep the night consistent, he also has leanings toward drone and ambient music, although he’s quick to dissect the benefits and problems of this term. “Ambient feels like a passive term,” he says. “I don’t think of it as ambient. I think of it as slow-motion. I want it to have the same sort of visceral grasp that dance music does.” Far away from Erik Satie’s furniture music or the Eno-inspired “as easily enjoyed as it is ignored,” McMurray wants, above all, presence.

McMurray notes a specific influence for this love of tangible music: his classical background. Having come from a family full of classical singers and piano players, McMurray was exposed to music and taught the piano from a young age. “I have a background of playing piano and organ,” he says. “I appreciate spaces and the way music sounds in spaces. So, doing something that is not rhythmic, something that has a wider presence that kind of captures you in a time and space, has a draw to it.” For example, using electronic sounds to replicate an organ resonating in a cathedral space leads to dense layers of music that gradually overtake this space.

This is where McMurray’s love of repetition comes in. Though the pace of dance and ambient music seem worlds apart, they both share the crucial element of near endless repetition. “The physicality of the sounds is what’s taking priority in what I do over something like song structure, and the repetitive nature becomes part of it. That’s kind of what’s required to get the muscle mass for it to work,” McMurray says. “It becomes more about physicality and process than anything else.”

This notion moves away from the conventional one of contemporary musicians, where the recorded version is the one, perfect, concise way of understanding music. “I want to be intentional about [the music],” says McMurray. “I would rather play it and not loop it, so there’s a deliberate move. This is the sound we’re going to hear, and if I stop doing it, it’s going to stop, and when I change it, it changes. Nothing’s on autopilot.” Of course, McMurray is quick to amend. “Unless that’s deliberately the decision,” he says, noting the beauty inherent in letting a complex system run itself.

This notion moves away from the conventional one of contemporary musicians, where the recorded version is the one, perfect, concise way of understanding music. “I want to be intentional about [the music],” says McMurray. “I would rather play it and not loop it, so there’s a deliberate move. This is the sound we’re going to hear, and if I stop doing it, it’s going to stop, and when I change it, it changes. Nothing’s on autopilot.” Of course, McMurray is quick to amend. “Unless that’s deliberately the decision,” he says, noting the beauty inherent in letting a complex system run itself.

In order to keep this love of presence alive, McMurray uses primarily analog synthesizers and instruments. “For me, having all of the ridiculous knob-per-function, patchable options is what works for me. I took the most difficult and ridiculous approach to something possible,” he says, laughing. While he may casually deride himself for his arsenal of wires and boards, his natural sounds and effects couldn’t be accomplished any other way.

McMurray’s gear room comprises close to a dozen synthesizers and controllers. The setup looks overwhelming to my untrained eyes, but McMurray deftly navigates the rig with skill. He shows off a few sounds, teaches me the basics of synthesizers, and every few minutes, he’ll pull cables from a number of different boards and instruments. He’ll occasionally mutter something like, “Let’s try this,” or “This could be fun,” as if he’s always looking for new sounds or styles to try out. As with everything he does in music, his approach to the synthesizer is a perfect blend of intense control and freewheeling curiosity: willing enough to let chance create something great, but talented enough to capture and replicate that greatness.