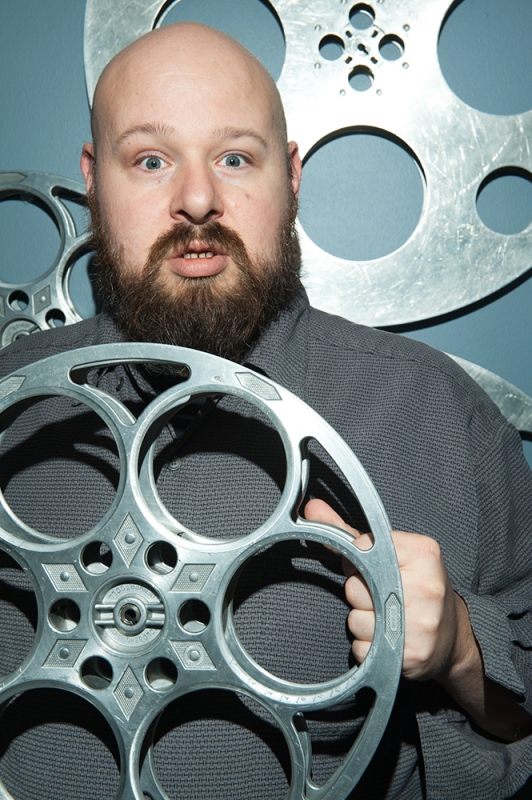

Lance Walker, Head Projectionist for the Salt Lake Film Society, has survived the digital conversion, though his job has considerably changed.

Image: Russel Daniels

The Dying Art of Light

Community

In his 2011 documentary series, The Story of Film: An Odyssey—consequently another Farley recommendation—Irish film critic Mark Cousins describes film as “the art of light.” He says, “[Thomas] Edison and the many other manic, ideas-y inventors of cinema realized that beyond the equipment and machines, what you needed most for movies was light”—essentially making the role of the projectionist somewhat of a poetic intermediary between the art and the audience. According to the first episode of the series, and confirmed by Walker’s extensive knowledge of traditional movie projectors, the actual machine is an amalgamation of varying components from other inventions, including the sewing machine and the vacuum, slowly tweaked by new innovations, but not as quickly evolving as one would expect compared to the technological advances surrounding it. Perhaps this is why, a year after Tyler Durden explains the basics of projector mechanics, the first digital projectors are installed and tested in a few movie theaters across the country.

Nearly 14 years later, the labs producing celluloid film are shutting down and movie studios big and small have finally caught up with the digital, economical and eco-friendly age, sending notices to theaters, independent and commercial, that they’ll no longer be producing 35mm prints. Instead of heavy, metal canisters of film, briefcases are arriving on theater doorsteps full of hard drives about the size of a paperback—compressed movie files. Large chain theaters, like the Megaplex at the Gateway, completed their conversion to digital a couple of years ago, but a quick search on Google reveals that independent theaters across the country are struggling to purchase the expensive new projectors in time to meet the studio deadlines—a story of its own. Salt Lake’s independent theaters have survived the changing of the guard, and at the Broadway, aside from two running 35mm projectors, the outdated machines have been pushed into even darker corners to make room for whirring blocks—looking a bit like oversized window units—topped with glowing touch screens. In one day, Walker laments, a century’s worth of invention and innovation was replaced. “Film” is a vestigial word now.

The job of the projectionist, though, is still very much alive, however changed. “I was led to believe that the digitals would take care of themselves, which they haven’t done yet, so I still have a job,” says Walker. “They never implied that I would be fired, but that I would have less to do. It’s all the same amount of work—it’s just different work.” Walker is now part DJ, part IT tech. His day begins by uploading or “ingesting” the movie into the digital projector, inserting special keys sent via email to decode the encrypted information, and then, essentially making a playlist that includes a schedule of showings, trailers, credits, etc. “When it was all 35mm, you would come in and turn on the power, thread up the movies, and you were ready to go,” says Walker. “Now, you have to make sure the machines are actually networked, and sometimes you have to restart them several times to make sure that they’re connecting. So it just takes a lot more time to get the day started, but other than that, you just put in the schedule and it goes. Then someone complains about it—the cleaning lights have been left on—and you’re like, ‘That’s not my deal—the machine left the cleaning lights on.’ When automation is going, it just makes people think it’s taken care of—‘I don’t have to worry about it.’ Digital is a fickle thing.”

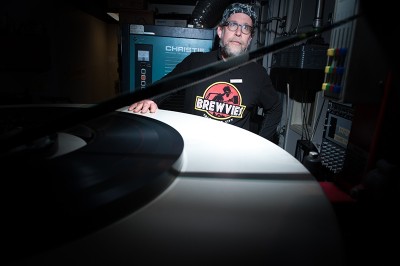

At Brewvies, the two back-to-back 35mm projectors have not been converted as of writing this article, though they’ll be switched out soon, but Farley sees the change as a positive one. “The idea of not having to use resources which are largely slandered, and ship items across the country that burn carbon—it’s going to be a great efficiency and a great good in a deep ecological sense to not have film,” he says. “The projection will always be significantly improved, because it’s really easy to flub a film and ruin it, and digital looks good now.” Walker agrees, saying, “I really think that whoever did the digitals went around and figured out all of the awful things that happen, and they did a really good job in putting their thing together.”

There’s no romanticizing 35mm film when you’re the one spending a whole night in the booth, putting together two miles of film after dropping a print—which Farley admits to having suffered on a couple of occasions in his early days as a projectionist. “That will never happen anymore—I will never have to look at a projector and think, ‘How do I fix this?” he says, pausing with what I read as a hint of poignance.

For myself, threading the film through the projector was a meditative respite from the rush of working as a barback. It was detail-oriented, mechanical work that satiated a compulsive urge. It was a small piece of art that I mitigated to an audience through a machine whose parts contain the genealogy of industrious and romantic ideas. The digital conversion has changed the mechanics of cinema, evolved the projectionist from a torchbearer waiting in the shadows to a button pusher glowing in the dark, but no one’s really crying about it. “It is, after all, just an aesthetic end you’re searching for,” says Farley. “There’s no quantity of truth you’re trying to get out of it because it’s a lie anyway—you’re just trying to get a really great lie.”