Salt Lake’s Secret Garden: Gilgal Sculpture Garden

Art

In 1947, Thomas Battersby Child retired as a stone mason and began construction on what would become one of Salt Lake City’s jewels. He called his backyard art project Gilgal Garden, and by the time he was finished, it would include 14 acetylene-carved sculptures made of stone found from across the state and over 70 inscriptions from mostly Christian texts.

In the same year, he planted an almond tree. In the Old Testament, the almond tree is a symbol of rebirth and hope. In the book of Jeremiah, God asks Jeremiah what he sees. He responds, “I see a rod of an almond tree.”

“Thou has well seen: for I will hasten my word to perform it… So will I watch over them, to build, and to plant, saith the lord.”

And so, like Jeremiah, Child built and planted.

A lifelong member of the LDS Church, Child also served as the Salt Lake 10th ward bishop for several years. He was a stonemason by trade and was as dedicated to his faith as he was his craft. Indeed, religious totemism underpins the entirety of Gilgal Sculpture Garden. Its namesake is an homage to the biblical reference in which one man from each of the 12 tribes of Israel took a stone from the bottom of the Jordan River and placed them in a circle as a memorial to God for stopping the flow of the river to allow them to cross into Zion. Child’s Gilgal is a tribute to what he believed was the new Zion.

A Place of Utah Magic

It’s probably—definitely—a cliché to say that Utah is a place of myth and lore. But it’s true. It’s what makes our state so unique and interesting. Originally Shoshone, Ute, Paiute, Goshute and Navajo lands, it was then colonized by Spanish conquistadors and then by mostly Western European LDS settlers. The cryptic place names, unmarked graves and biblical iconography throughout the state reflect its bizarre and brutal mashup of cultures.

Gilgal Sculpture Garden bares the lore that makes Utah so delightfully weird. It’s hard to know what Thomas Battersby Child thought would become of the garden when he started it in 1947. Did he intend for it to be a public park? Or was it just his way of making meaning of the world? It’s hard to imagine a project as ambitious as Gilgal would ever remain private, whether intended or not. Yet in a digitally archived handwritten note preserved by Gilgal Sculpture Garden, one quote of Child’s suggests that it was his intention to make the garden a public space:

“Can I create a sanctuary or atmosphere in my yard that will shut out fear and keep one’s mind young and alert to the last, no matter how perilous the times?”

But what Gilgal has become is incredibly rare, and not what one would expect given its creator’s dedication to his faith.

70 Years of Gilgal

Nearly 70 years after Child started the garden, the times feel increasingly perilous. How many places are there like Gilgal—a public space, not necessarily for worship but for people to wander, lie in the grass and interact with the physical manifestations of one man’s thoughts about humanity, God and existence—a space in which one does not bear the burden of being commodified? There is no fee to the garden. There are no advertisements, nor are there vendors. In the heart of an ever-growing city, tucked dreamily away behind old homes with overgrown yards and shadowed by a parking garage, Gilgal stands in quiet defiance of a society concerned more with answers and understanding than it is with questions and unresolved pondering.

I don’t know if Child’s idea was more or less radical now than it was in 1947.

Gilgal is a hard place to write about. Probably because, generally, writing about a subject implies an idea of understanding. But that’s not how Gilgal works. Anyone that takes a walk through Gilgal and comes out saying “I get it” is a fool. Child himself even invokes intentional ambiguity in his sculptures in more places than one.

Even Judi Short, President of Friends of Gilgal Garden, the group that fought to preserve the garden initially and still spends tireless hours every week to maintain it, revels in its ambiguous beauty. “I’m not LDS, so I don’t understand the scriptures like a different observer might,” says Short. “But I really love it all.”

One Weird Sphinx

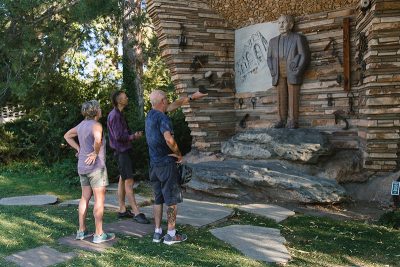

“The Captain of the Lord’s Host,” for example—the statue directly across from the sphinx—represents the captain who appeared to Joshua and gave him a plan to assure the Israelite’s victory over Jericho. Atop the statue, where the captain’s head would be, is an un-sculpted boulder. Frequently asked if he intended to carve a head, Child replied, “No, I intend to leave it as it is, thereby taking advantage of the liberties of modern art.”

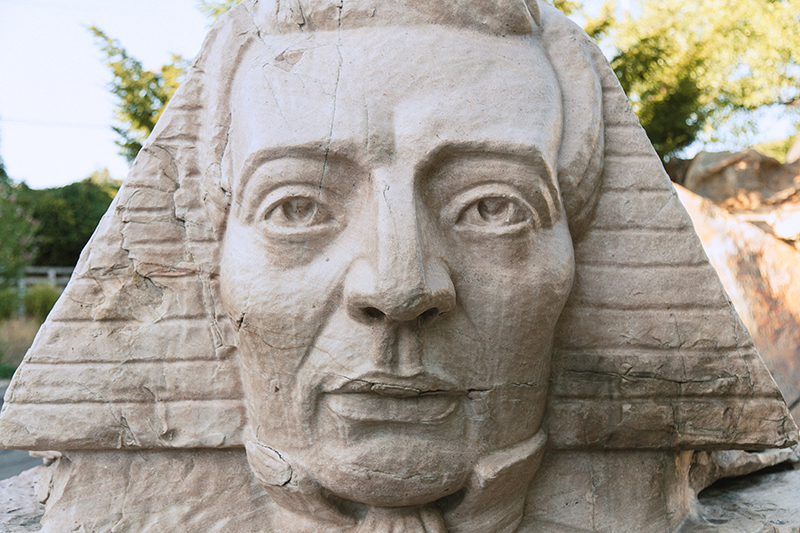

Yet, the most striking sculpture in the garden, the Sphinx, is so eerily weird and cryptic that it begs to be understood, begs to be answered.

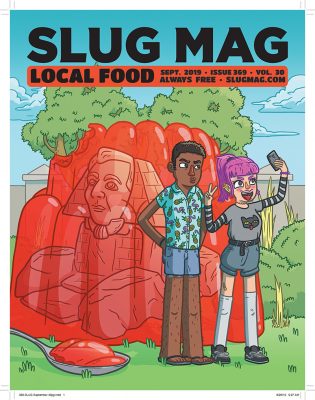

It rests near the entrance of the garden, some eight feet high with the face of Joseph Smith staring down the walk at all who enter the park. It’s the sculpture that SLUG illustrator Spencer Holt (@spenturion) depicts encased in Jell-O (Utah’s official state snack), on SLUG’s September 2019 Local Food issue. This sculpture is exactly the kind of weird that I’m talking about—the kind of weird that I love about Salt Lake. Nearly every Salt Laker has some kind of complicated relationship with Joseph Smith, and here was his chiseled-stone face on the body of a sphinx? I was gonna get to the bottom of it.

The sphinx is a symbol of mystery and of dread. The term “sphinx” comes from Arabic, literally meaning “the father of dread.” In Greek legend, it poses a riddle to all who encounter it, devouring those who attempt in vain to answer it.

Gilgal’s Wonderful Ambiguity

It took two weeks for me to finally realize the irony. I was trying and failing to research, understand and explain this statue. All until I read the words of Child himself, quoting Henry Adams (who commissioned the famous Adams Memorial by Augusts Saint Adams and Stanford White, which inspired his sphinx):

“‘It was meant to ask a question, not to give an answer; as the man who answers will be damned to eternity like the man who answered the Sphinx.’ This statement of Henry Adams is the basis and stimulation of my thoughts which lead to the construction of the sphinx in my yard,” reads a document preserved by the Gilgal Sculpture Garden.

That is the essence of Child’s Gilgal Sculpture Garden. Not to beg answers, but to ask questions, to pose riddles. As Child himself put it, “It is sometimes more potent to suggest and cause wonderment than to explain in detail.”

In 1947, Thomas Battersby Child planted an almond tree. It died the same year he did, in 1963. For 30 years, Child’s garden was closed, and nearly sold to developers to make way for condos in the late 1990s. In 1999, after community members fought to preserve the garden, Gilgal was reborn to Salt Lake City as a public park and a new almond tree was planted.

More on SLUGMag.com:

Fred Conlon: Garden Art That Doesn’t Suck @ Utah Arts Fest

Rich Soil: SLC Artist Siri Elaine