Review: Beren and Lúthien

Book Reviews

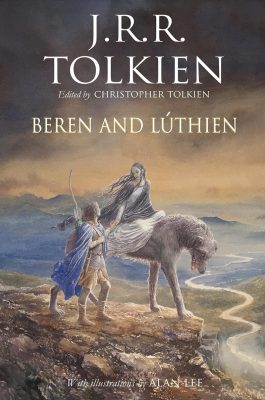

Beren and Lúthien

J.R.R Tolkien

HarperCollins

Street: 06.01

In the trenches of the Somme, in a world his faith told him was made by a loving God now fallen to war and tears, J.R.R. Tolkien learned what humanity’s long defeat meant. Despite war, there was courage. Despite despair, there was hope. Despite fear, there was Edith Tolkien. For the rest of his life, he would ponder this alchemy of terror and triumph via the tale of Beren, the outlaw man who fell in love with Lúthien, divine elf princess who dared challenge all the lords of Hell for him. The drafts of this tale have been collected anew in Beren and Lúthien by their third son, Christopher Tolkien. Throughout them all is the common thread of Tolkien’s undying passion for the love of his life, Edith.

Tolkien met Edith Bratt in 1908. Both orphans, both romantically imaginative, they quickly fell in love. However, Tolkien’s guardian, Fr. Francis Morgan, forbade him to see her until his 21st birthday, owing to his studies and her Anglican faith. Tolkien, an unsurprising but just authoritarian, disobeyed only once to notify Edith of this command. He lay no obligation on her to wait, and indeed she did not. On the eve of his 21st, Tolkien wrote Edith professing the persistence of his love and proposing marriage … only to find she’d become engaged to someone else. However, she agreed to meet him, and by the end of Jan. 8, 1913, she accepted his proposal—the proposal of a man, in Tolkien’s own words, with no job, little money and no prospects except the likelihood of being killed in the Great War.

The young couple’s anxiety going into World War I was acute. Edith lived in fear every knock would bring news of her husband’s death, and Tolkien lost all but one of his childhood friends. To allay his wife’s fears—and no doubt his own—Tolkien devised a code so that she could track his movements on the Western Front, but death seemed no less certain. As historian John Garth would later quote in his book Tolkien and the Great War, Tolkien said, “junior officers were being killed off, a dozen a minute. Parting from my wife then … it was like a death.” When he was struck down by trench fever and returned to England, it was only just in time to evade his entire battalion being slaughtered. In this madness of blood and death, Tolkien and Edith filled each other with life. In 1917, they had their first son, and in 1918, Edith danced for then lieutenant Tolkien in a woodland glade among flowering hemlock. In that moment, the Tale of Tinúviel, the fairy-tale first draft of Beren and Lúthien, was born.

You see, Beren, fleeing the authority of that greatest Luciferian king Morgoth, came upon Lúthien dancing just the same way. He fell in love with her at first sight, and though she fled from him initially, she, too, came to love the simple adoration on his kind face. They became one another’s irrevocably, which pleased her father, the great elf-king Thingol, none too much. When Beren asked for her hand in marriage, Thingol charged the simple human rogue to pay for it with a Silmaril, a jewel filled with the light of heaven currently resting upon the iron crown of Morgoth, condemning him to certain death.

Does any of this sound familiar?

Unlike 2007’s the Children of Húrin in which Christopher assembled his father’s piecemeal drafts into a coherent text, Beren and Lúthien has been left in its various parts. Between each is inserted commentary to provide what context is required to proceed with the narrative. This is presumably because much of the story was written as the Lay of Leithian, an impressively complex poem that was still unfinished at thirteen cantos long. Neither losing nor duplicating the style seems to have struck Christopher as feasible—for this, he can hardly be blamed. If this disappoints and discourages you from reading Beren and Lúthien, then please trust that the emotional effect is not lost by this delivery. The story still flows with only minimal dissonance and this method allows for the earliest draft to be included. Moreover, there’s really something quite touching about Christopher’s continued presence in the text; though he restricts all rumination on his parents’ romance to the preface, the intimacy of their son detailing evolutions in their fictional counterparts is palpable and moving.

However, if you’re not interested in the biographical tensions at play but were instead eager for more Middle-earth lore, then you should still read Beren and Lúthien. Casual fans of Lord of the Rings will get, for the first time, real characterization for Sauron, most directly as Thû the Necromancer, and most humorously in his first appearance as Tevildo, Prince of Cats. Those who find elves boring in their judgmental perfection will enjoy the complexities of Thingol’s pettiness, Celegorm’s lust, Curufin’s treachery. Finally, anyone who found Lord of the Rings’ prose nigh inaccessible will be refreshingly surprised by the playful, lyrical style of Tolkien’s youth.

This is assuming, of course, that you have not read the twelve volumes of the History of Middle-earth in which all of Beren and Lúthien’s drafts were previously published. If you have, this book is more remix than revelation and needs only to be picked up if you believe you’ll gain new emotional appreciation for the content. I certainly did. As stated above, Christopher doesn’t remark frequently on the emotional parallels between the central characters, but admits that it was chosen for collection in memoriam and one ought read it with an eye for these parallels. When Lúthien amuses herself by pulling on werewolf-Beren’s tail to his anger, it’s only too easy to see Edith teasing her Ronald the same way. When her Ronald gives Lúthien every major victory in the text, one’d have to be blind to miss the fawning adoration in this gesture. And when you remember that when Edith died, the irrecoverably despondent Tolkien had “Lúthien” engraved upon her headstone and left instructions that “Beren” be put upon his—well, there’s nothing to see for the tears in your eyes.