Book Review: Verge

Book Reviews

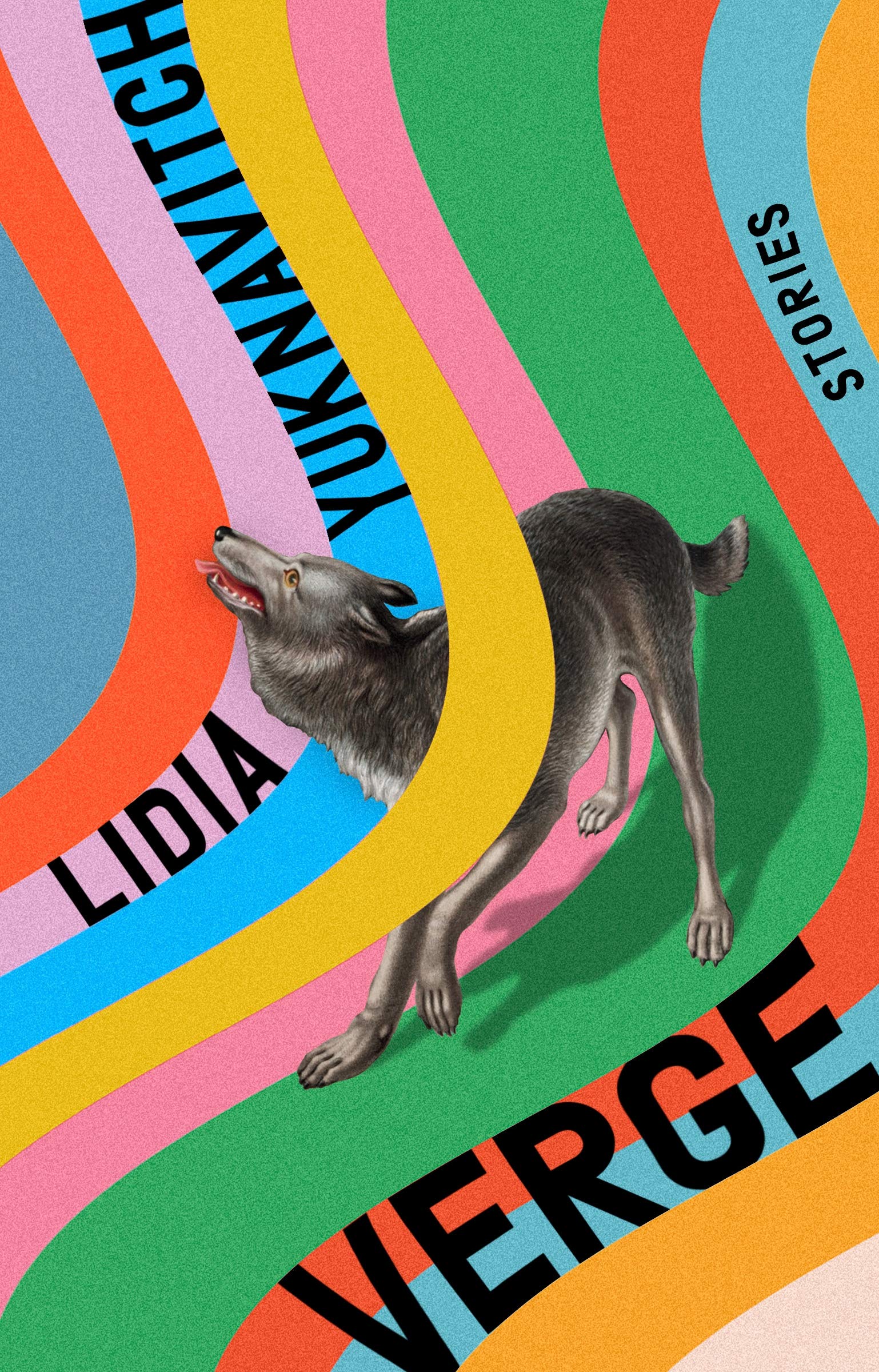

Verge

Lidia Yuknavitch

Riverhead Books

Street: 02.04

I most frequently read short-story collections, and Lidia Yuknavitch’s Verge has everything I want from one. Considering it as a whole, Verge simply feels replete. Its stories create a subdermal web that coheres and refracts the collection with motifs of feminism, middle-class imposter syndrome, isolation and more—but those words alone would be reductive to Yuknavitch’s sheer artistry and inimitable inflection as a writer.

While various stories in Verge are concerned with feminism, much of the marrow lies in the barriers created by patriarchy, how women are forcefully socialized by its constraints and her characters’ struggles in navigating/finding themselves within these boundaries. The protagonist of “The Organ Runner” subverts her role as an orphan by excelling in delivering people’s organs, and furthers this sensibility in exacting revenge against a boy who’d assaulted her. In “Second Language,” an Eastern European folktale irrupts into reality, wherein a human-trafficked sex worker mutilates herself to invoke wolves that “ripped the throats from the wrongheaded men and tore them limb from limb.” Conversely, in “Cusp,” the protagonist arrives at an epiphany that the sexual liberation she experiences with men in a nearby prison still pits her against slut-shaming and within patriarchal confines that delimit any kind of liberation she may experience.

Yuknavitch’s feminism intersects with class struggle, as seen in “Street Walker.” The protagonist of this story queries her middle-class position as she considers creating a safe space for a sex worker she observes on her street. In this intersecting, Yuknavitch successfully brings to the fore the frustrating paradox that being a savior for women also implicates us in class discrimination, baring our society’s snake-eating-its-tail dynamic. Further into the class trope, “Woman Object (Exploding)” finds its feisty protagonist put off by the fake people at a pretentious dinner party. As she gets progressively drunk, she views them as caricaturesque animal versions of themselves in an absurd, solipsistic, academic milieu. Given that Yuknavitch is a professor herself, the self-awareness and class-cultural critique is resounding.

Verge isn’t all social critique, per se. “Mechanic” is a lesbian love story approaching (but not quite reaching) pornographic territory in a tasteful, feminist kind of way, as the mechanic protagonist feels out if the femme, engaged customer is interested. “A Woman Apologizing” proffers some navel-gazing as a woman expects her lover to return to her after a fight. The objective correlative of her being handcuffed to a bed as a forced symbol of her relinquishment of control—the cause of the argument between her and her boyfriend—becomes her Icarian downfall as she finds herself waiting longer than she expected for him to return and make up.

Yuknavitch excels in translating trauma into her fiction. “How to Lose an I,” the penultimate story, follows a man who lost an eye and his lover in a car accident. It’s a prime example of Yuknavitch’s penchant for weaving together themes via images—in this case, the protagonist’s comfort in being cradled by a car, ironically, conflating that with the comfort he feels while floating swimming, and it all mirroring the prosthetic eye he must wear. It’s one of Verge’s longer stories alongside “Cusp,” and those two are my favorites. I’m enticed to read one of her novels now.

By and large, Verge is for women. This is made even more apparent in its celebration of gender performance in “A Woman Going Out,” in which the ritual of shaving legs and putting on tights harmonizes with its pairing with the image of male genitalia. Opening story “The Pull” tells of two sisters swimming away from a wartorn country, and “Two Girls” touts flirtatious, lyrical, repeating language that plays with the physical contact of two 16-year-old girls. With each complex piece of this mosaic, Verge is a fantastic read all around. –Alexander Ortega

Purchase Verge from the publisher here.