“An Irreplaceable Refuge for All of Us”: nan seymour on the Great Salt Lake

Activism, Outreach and Education

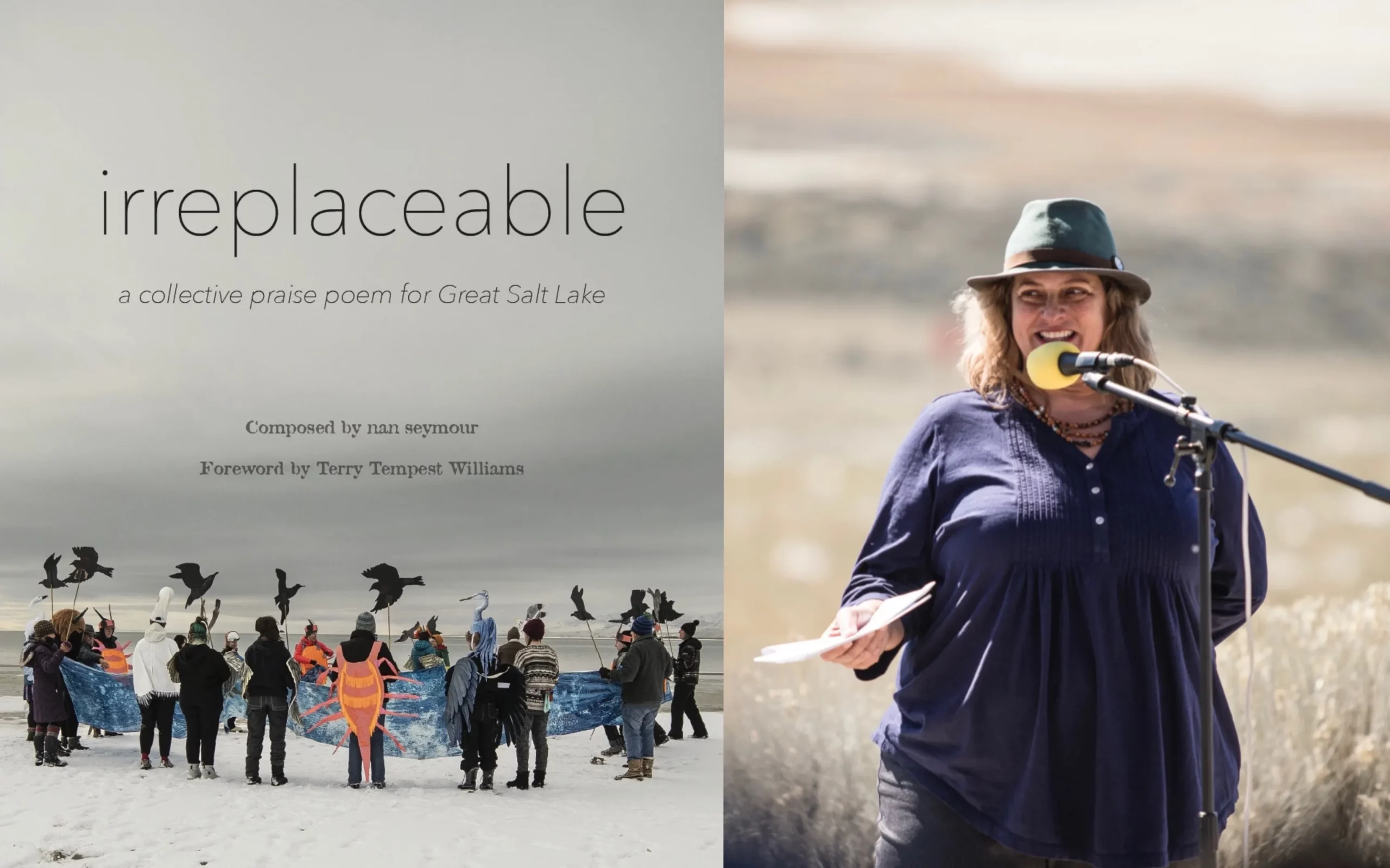

Poet nan seymour has lived for 50 years within what she calls the bioregion of the Great Salt Lake. When she learned that the lake was facing environmental risk, she put out a call to her writing community. The output was a collective praise poem that was recently released in a book, titled irreplaceable.

SLUG: Tell me a little about the recent release of your book irreplaceable, which you call a praise poem for the Great Salt Lake. What first inspired it?

nan seymour: It is a book and a poem, but it really is a project. I started in the fall of 2021. I had lived here for 50 years, but I really didn’t know the lake was in trouble. I heard a story on NPR’s Radio West with Doug Fabrizio about two scientists who wrote an obituary for the lake. The reason I think that’s so interesting is because they were trying to get people’s attention about this incredible crisis and got in through a piece of art. They used their creativity and employed something totally unconventional. I listened to that story and it changed everything. After that, I turned to the tools I had—primarily writing and community—which I have been fostering for the last decade in the River Writing Collective.

I should also mention Utah State Poet Laureate Lisa Bickmore. She deserves ample credit for bringing these poems into print with her small press Moon in the Rye. Her love and labor brought the book into being.

SLUG: You call this a praise poem. How did you bring in the community to produce a collective piece of art?

seymour: The idea to collect the poetry was in part inspired by Joy Harjo’s poem called “Praise the Rain.” Poetry can magically hold all of the layers. The collective work has different voices, like a brine shrimp farmer and sixth graders on a field trip. These are different perspectives and voices looking in the same direction. You could just engage on a literal level and learn so much about the lake. Under all of that, though, there is a layer that could be described as spiritual. The lake is big enough to meet you where you are. Poets describe the lake as a midwife, a mentor, a grandfather—encapsulating different roles [and] pronouns. It creates a rich tapestry, and you get a feel for the size of the cloth. Although there are about 66 individual contributions in the book, there are more than 450 voices represented in total.

SLUG: There is a lot of physical description of the lake in the poems. How does this sensory experience amplify the message you are trying to convey?

seymour: I’m an animist, so I believe that I can listen to trees and birds. I don’t really subscribe to the habitual human hierarchy in our culture. I think that that kind of listening, when you’re humble, is an essential piece of it. I started dreaming about the lake and poems started coming to me. I grew up in Holladay, when it was still horse country and part of the mountain. My early friends, beside my siblings, were scrub oaks. I had a sense that every life around me has a soul. Plants, animals, water bodies and even rocks are sentient, singing, communicative and available as friends. They have plans! This is my worldview.

SLUG: And how has that relationship with the natural world impacted your relationship with the lake?

seymour: The lake has so much intelligence and memory. She’s been around for a while. I think that particularly water has memory. My mom told me a story about the first time she floated in the lake when she was nine. She was with her mom, my grandmother. I realized that the lake remembers my mother, my grandmother, like you would remember the shape and weight of their bodies. That’s pretty intimate.

SLUG: You said after you heard the interview on Radio West, you started going to the lake and even started camping on the shoreline. Tell me more about that.

seymour: I felt invited by the lake to go to the shore and be there. The original invitation came to me in a dream to go to the lake from Wolf Moon to Snow Moon, which that year coincided with the opening of the legislative session. That didn’t feel coincidental to me. So I pursued the opportunity to live at the lake during the legislative session and asked for community support. We kept a presence at the lakeshore for 24/7 for the seven weeks of the legislative session. For the 2022 and 2023 legislative sessions, we were on Antelope Island throughout winter.

SLUG: What about this year? How was the 2024 legislative session for you all?

seymour: We’ve had a big shift for 2024. We were at the State Capitol every day of the legislative session, holding a vigil for the lake. We’ve started building giant puppets. We’ve built human-sized brine shrimp, mostly made from garbage. It just seemed like what the lake was asking for.

SLUG: The term “irreplaceable” is specific and frankly provocative. How did you land on that word? What meaning does it carry for the current state of the lake?

seymour: I feel like that word was gifted also. It’s just the bottom line. She is irreplaceable. I first encountered that description on a park sign in Farmington Bay. The bay is described as an “irreplaceable refuge.” Of course, [this was] referring to birds. But it’s an irreplaceable refuge for all of us.

SLUG: The collection evokes both celebration and mourning for the lake. How do you view this balance in the art that you are creating?

seymour: I had a dance teacher who was my primary creative mentor for my long life. She died of cancer about five years ago. When she knew that she was at the end of her life, she had a celebration of life while she was still alive. Her dance students over the decades came to her house and we danced in her living room. Though she was about a month from dying, she still had a lot of vitality. She got up and danced and I don’t know if that’s what this is, but if it is, it’s still worth doing—celebrating whatever life is left. I think celebration and reverence are forms of resistance.

The more vigorous hope is that we are changing the culture. Because even if we change all of the laws in favor of the lake, it won’t hold unless we change the culture. Culture defines our values and our values determine how we live. I get that it’s a long game in the face of an emergency and I get how frustrating that is. But we have to move forward without knowing the outcome. We have to make our best offering without knowing if it’s for our lifetime or for those that come after.

I really care about the question, “How can we save the lake?” But there’s a question deeper than that that really matters and it’s, “In the face of this crisis, who will we become?” And I think art can help us answer that.

SLUG: The collection evokes both celebration and mourning for the lake. How do you view this balance in the art that you are creating?

seymour: People ask why we are celebrating a dying lake. And we do it, because she’s still here. She’s still vital and alive. What we are really trying to do with the vigils is to demonstrate love and make the love visible and make the movement beautiful and hopefully irresistible and invite everybody. That’s the ethic, everybody is invited. It’s multi-generational. It’s multi-cultural. It’s accessible, free. We just want people to join us. Everyone is needed and everyone is qualified.

Listen to the Radio West interview between Doug Fabrizio and Dr. Bonnie Baxter, professor of biology at Westminster College and director of the Great Salt Lake Institute. Read irreplaceable online (or purchase a print copy) at irreplaceablepraisepoem.org and learn more about the River Writing Collective at riverwriting.com.

Read more stories about the Great Salt Lake:

The Great Salt Lake Institute’s Scientific Perseverance

The Anarchy of Dance in “Lake Bodies”