Seeing Yellow: Anne Fudyma

Art

When I walked into Anne Fudyma’s studio space at Captain Captain, her four main pieces and their accompanying sculptures were tacked onto the wall, a sort of mockup presentation. “Did you do this for me?” I asked. “Sort of,” she said. “I was experimenting. It’s kinda setup for you, but it’s mostly for my own personal gain.” The paintings all experiment with the color yellow, each informed by four years of buildup between Fudyma and the color, a culmination of her experiences with perception, relationships and the physical act of making art. But most of all, the series is a meditation on process, the digestion that churns all of our individual perceptions.

The obvious question I was afraid to ask Fudyma was, “Why yellow?” It seemed too simplistic to ask, too on the nose. And in a sense, it is too simplistic. I found so much to ask Fudyma before arriving at that question, and it’s because these abstract collages of shapes, symbols, colors and structures are much more about the concept of processing the world around us than they are the color yellow. “I feel like with my painting practice I talk about broad concepts, then go deep into these little subsections,” Fudyma says. “I’ve always said my paintings are based in time. They’re very process oriented, like maps or documentation of existence. I don’t plan my paintings. It’s a give and take—the painting’s teaching me, I’m teaching the painting. We work together, these different versions of myself.”

Around 2014 Fudyma kept noticing what she perceived as the color gold. It was a subtle framing, gold over yellow, and it was when her then-partner talked about gold using the word “yellow,” she noticed the dissonance between their perceptions of what could have read as the same thing. Yellow came to engender this dissonance for her years later when she was invited to do a show in Portland, which she titled, It Was Never Yellow. But because the gallery didn’t allow people to walk inside, only to see through the street windows, this setup worked completely against her. “There was a bright yellow building,” Fudyma says. “Bright yellow, plastic, like neon, right across the street. So during the day, if you looked at the gallery, it was like there was this yellow film [over my work], and I was like, ‘Here’s this fucking yellow again! Why’s this coming back to me?’”

Fudyma decided to lean into it, to wrestle more with the intrusion. “That’s where yellow as pain started. That color hurt to look at it, and it was blocking my work.” Literally. What started as a way to understand rifts in perception became a concrete vehicle for investigating abstract concepts. She began immersing herself in the color, trying to dwell in it on a base level, buying yellow products and using yellow materials. “I was even drinking yellow beer,” she says. Eventually one of her friends commented on her paintings while taking pictures for Fudyma’s website. “It’s so pretty,” she told her. “It’s cheery! It reminds me of the sun.” Fudyma couldn’t see it. That was not the yellow she saw.

“It’s such a bad color … I actually hate yellow,” Fudyma admits, laughing. “That is why I think it’s a thing I’ve been working with since 2014, because to me yellow does mean so much, and with this I’ve been trying to be like, ‘What part of yellow am I investigating?’” It’s part of the larger practice of repetition, of letting things come naturally. Ideas recur and recur—and why?

Today Fudyma has answers. Yellow is loss and renewal, sickness and joy, the ebb and flow of energy. Yellow, unwatered flowers accompany her paintings, reflecting a persistence in the face of decay. We talk about how the local Smith’s briefly changed their plastic grocery bags from brown to yellow and the strange sensation of becoming acutely aware of something that was invisible before.

Today Fudyma has answers. Yellow is loss and renewal, sickness and joy, the ebb and flow of energy. Yellow, unwatered flowers accompany her paintings, reflecting a persistence in the face of decay. We talk about how the local Smith’s briefly changed their plastic grocery bags from brown to yellow and the strange sensation of becoming acutely aware of something that was invisible before.

Fudyma is upfront about these interpretations, partly because she doesn’t necessarily expect the audience to share those associations and partly because those associations are the direct result of the creative process. Her piece “Maybe It Looked Yellow to Me” is the most dense in terms of concrete imagery, collaging a horse skeleton with knotted chains; large, exacting shapes with words like “tired” arranged backward in old English typeface. These all mean specific things to Fudyma she doesn’t expect anyone to intuit.

It Was Always Yellow is a deft interpolation of the concrete with the abstract, grounded in the gut of familiarity but disconnected from anything absolute or fixed. “I’ll paint something, and I’ll leave. I’ll come back, and I’ll paint over it or paint with it,” she says. “It’s my present self and my past self interacting with each other … they’re overlapping. They’re avoiding. They’re working.” It’s a loose process that aims to explores the exact notion of process, letting Fudyma mix discovery with intentionality.

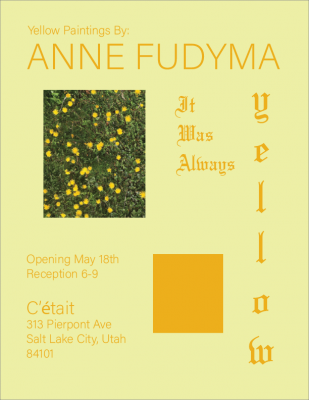

Capacious in color and capricious as a signifier, Fudyma’s work reminds us of art’s ability to deceive us into a certain perception, intentional or not. It Was Always Yellow will have an opening reception May 18 from 6–9 p.m. at the new C’était gallery on 313 Pierpont Ave. Come experience the capacity of yellow, the obviated sun, the nausea, the cramped and stifled room, the parting of the clouds and, maybe most importantly, the reflection on the process.