Pattern Perception: Knew/New

Art

Despite being all around us, patterns are often relegated to the functional: wallpaper, phone backgrounds, flooring and decoration, even the brush along a mountainside or line of trees down a suburban road. Patterns and repetition are an omnipresent form of art (and nature), in some ways designed to blend in as much as they do. Rachel Henriksen’s exhibit knew/new at UMOCA takes this blindspot and plays with patterns’ ability to normalize perception, finding the points where breaking that perception and reshaping it creates moments for critical reconsideration.

Each work at the exhibit is untitled, but there is a sense of conceptual progression if you view the gallery moving left to right, (east to west). The first piece hangs loosely and without a firm canvas. Instead the piece is positioned on a paper that looks like it sat in the sun too long. Depicted is a simple pattern of red circles that ring a core of olive circles, a dark green color filling the spaces in between. Like the paper canvas itself, the pattern distorts in areas as though it just came out of the oven. The pattern is not a pattern in the sense that it repeats perfectly, but it is a pattern in its ability to—at first glance—make an oozy texture feel prim. The closer you inspect, the more easily you absorb it’s achievement of simultaneously functioning as a pattern while disregarding the form.

“Each work at the exhibit is untitled, but there is a sense of conceptual progression if you view the gallery moving left to right, (east to west).”

Shifting awareness and evolving forms are the core experiences that make up knew/new. Below the first piece is a small, framed pattern made on graph paper. It’s a square shape of red diamonds inside gold and blue squares. A gold-trimmed border intersects at each corner into another diamond, empty of color except for a single one at the bottom left. Much the same to the work above it, the detail isn’t something you notice unless you pay it a kind of attention that initially feels more involved than what I suspect most people’s relationship to patterns would merit. Engaging with this mode of art directly evokes the Pattern and Decoration Movement of the mid-1970s–80s and its push to create a presumption of beauty in an art space that had been considered feminine and therefore unworthy of the rigorous thought and dissection that comes with an art label.

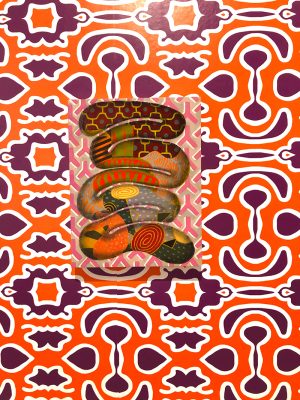

The next pieces more obviously resist easy interpretation, and they also play with the form more outwardly, too. One of the pieces features two layered works, one on paper and another on canvas that sits on the bottom-right quarter of the first. The bottom piece shows a thin, yellow-grid pattern on a blue background. The grid breaks vertically at the left, and the horizontal lines connecting the grid suddenly reveal themselves as offset and lacking each other, leaving a small space in between. This rift breaks form, and so enters the second piece of the work, a green canvas with a blue, reflected flame creating its pattern. But what lies on top of the pattern here is a shape that itself will repeat throughout the show: a round, tube-like shape that folds back on itself, much like a bowel.

“Shifting awareness and evolving forms are the core experiences that make up knew/new.”

Inside the bowel, different patterns cut into the shape and mix together, existing non-contiguously as though you had textured the shape using the patterns of other pieces. It creates a feeling of “art invading art,” of different forms and concepts finding themselves a part of each other, sometimes fittingly and sometimes not. Throughout the rest of the exhibit, Henriksen only finds more ways to build into this sensation in her play with form and pattern. A black-and-white checkerboard piece begins as a grid then distorts as though gravity were pulling it inward. In its middle, the lines conform to a straight grid again, but it feels as if it’s a layer below the outer grid. It begins somewhere simple and unremarkable, distorts and reimagines its own form, then reverts to something familiar, now couched in a movement of rupture.

Continue along this line of thinking, and the rest of the exhibit only becomes more potent food for thought. The abstract nature of the exhibit means you might need to shift your brain into a weird gear for weird thinking, but the headspace is genuinely fun to poke around and pose thoughts in. A late piece shows the bowel-like shape travelling between two canvases. The bowel is filled with contrasting patterns as it sits in the canvases but remains white, blank and inert, where it sits between them. It’s as though a creative energy, rooted in the body and nature through its gut shape, penetrates the patterns and decorates them with life. The canvas works with the fluid tube shape to make formal art, both by providing a frame and by conferring the status of art through its rigid dimensions.

“The abstract nature of the exhibit means you might need to shift your brain into a weird gear for weird thinking, but the headspace is genuinely fun to poke around and pose thoughts in.”

Knew/new is full of formal arguments like these, and if you’re willing to break your thought patterns alongside the breaking visual patterns, you may find yourself thinking new, bold thoughts. The exhibition runs at UMOCA through Jan. 18. Find more information at utahumoca.org.

More on SLUGMag.com:

Desire Lines at UMOCA: Jane Christensen

Art as Wellness: UMOCA’s See Me Exhibit