Chiura Obata: An American Modern

Art

There are a handful of adjectives I find myself and others using when we describe Chiura Obata’s works—simple words like vibrant and lively, delicate and beautiful, always in the language of life. If you haven’t seen Obata, it’s hard to describe. I love Obata’s ability to evoke livelihood, even in the most mundane subjects. It’s enough to feel masterful, completely overdue for this retrospective. But on the whole, his work signifies him as a modern artist who brought Japanese traditions to European-American modernism, creating a blend that captures the nuance of the emigrant identity and assimilation into a perception of Western culture and the people who create it: who gets to envision the world and whose perception is placed to the side.

The exhibition (Chiura Obata: An American Modern, showing at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts through Sept. 2) is a fraction of what Obata produced, but is still fairly representative: There are works from each decade of his life and examples from his different styles and mediums, such as sumi-e or his woodblock prints. His history and his ability should feel intertwined—for all his accomplishment and recognition, he was alive during World War II and subject to the internment of Japanese Americans. First incarcerated at Tanforan Assembly Center in California and then here in Utah at the Topaz War Relocation Center, Obata retained a notable vitality throughout his artwork as an internee and artist post-WWII that has become something of a signature.

Born in Okayama, Japan, Obata emigrated to the United States in 1903 at 17 and worked as a domestic servant in San Francisco. Eventually, he earned a living as an illustrator, notably working for San Franscisco’s two Japanese newspapers. Obata eventually became a leading figure in northern California’s art scene and as an art professor at Berkeley for 22 years, and by then, he had created so much: On display, we see early nihonga (Japanese-style paintings) studies from his youth in Japan where he studied in Tokyo. We see his Japanese ink paintings, sumi-e, of pandas, pots, devastations and earthquakes. We also see his drawings from internment at Topaz. Rather than fixate on the well-accepted fact that the 1942 Japanese Internment was a human rights violation, the show instead deftly operates on a different argument: “We want him to be part of the canon,” says ShiPu Wang, curator of the exhibition. “We want him to be part of the conversation of American art as opposed to always having to qualify him as a ‘Japanese Artist.’” By collapsing the artistic identity of Obata from Japanese American artist to simply American artist, you expand the canon of 20th century modernism in a way that necessarily accepts internment as an American experience perpetrated against itself rather than against its others. To categorize Obata’s work outside the American experience literally sequesters Japanese American work to only its own history—and though it has a rich and varied one, it must also be recognized as an equal component of American art. Obata does not lose his place in the Japanese American canon simply because he has a place in the American.

And of course, internment casts its shadow today. Unchecked executive arms like ICE continue to lose track of immigrant children, and the U.S. has been deporting people in massive numbers since it was originally colonized, no matter the controlling party. We live in a country whose state agitates the politics of our art, and so Obata’s drawings of students bustling at U.C. Berkeley must stand with his drawings of internees huddled on wire beds.

Ultimately, Obata’s work lives above the realities it captured, and it’s this sense of freedom Obata mastered that other art writers and I have tried to express. Wang, the curator, asserts that the most provocative thing about

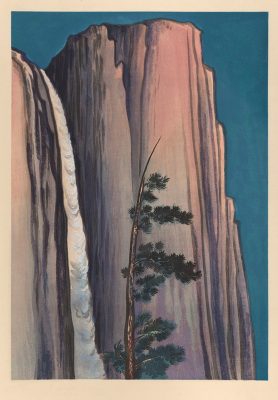

Obata is how he manages this freedom while challenging our own sense of how Eastern, Western and cosmopolitan influences are interacting throughout Obata’s works, as well his life. Serene paintings like “Evening Glow at Yosemite Waterfall” share a calmness with the people in “A Sad Plight,” huddled together in small blankets. “Southern Shore of Salt Lake” is so evocative in such simple brushes. Obata often works in broad strokes to great effect, such as in “Dust Storm, Topaz” which practically feels like it’s moving as the dust swirls over and across camp buildings. The result is a way of looking at the world that always has an ineffable quality to it, one I loved. There was not one of Obata’s works I didn’t care for. I wanted to look at each and every one and see what he saw.

An American Modern has a lot of firsts. It’s the first touring exhibition of Obata’s work that includes work from all decades of his working life. It’s also the first time his works have been presented as a collective retrospective in Japan, since they’ve only shown in fragments before and not always translated. But perhaps most importantly, one of the next stops for this exhibition will be the Smithsonian, which marks Obata as an American Modernist in the larger artistic canon, a place he has every right to be, recognition long overdue.

You can see Chiura Obata: An American Modern through Sept. 2 at the UMFA, open Tuesday to Sunday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and to 9 p.m. every Wednesday at 410 Campus Center Dr. Visit umfa.utah.edu for more information.