Bodies in Space: Rona Pondick and Robert Feintuch at UMOCA

Art

Painter Robert Feintuch and sculptor Rona Pondick each embrace the long lineage of humankind’s fascination with the body and the figure. Their artistic practices capture the body in curious and suggestive ways, and both incorporate their own bodies into their art. Despite these ties, Feintuch and Pondick—who have been a couple since the mid-1970s—create separate and vastly different bodies of work, but until recently, hadn’t substantially exhibited their work together. Organized by Director of the Bates College Museum of Art Dan Mills, Heads, Hands, Feet; Sleeping, Holding, Dreaming, Dying is the first extensive museum exhibition of both Pondick and Feintuch’s work. The exhibition will be on show at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) through July 15.

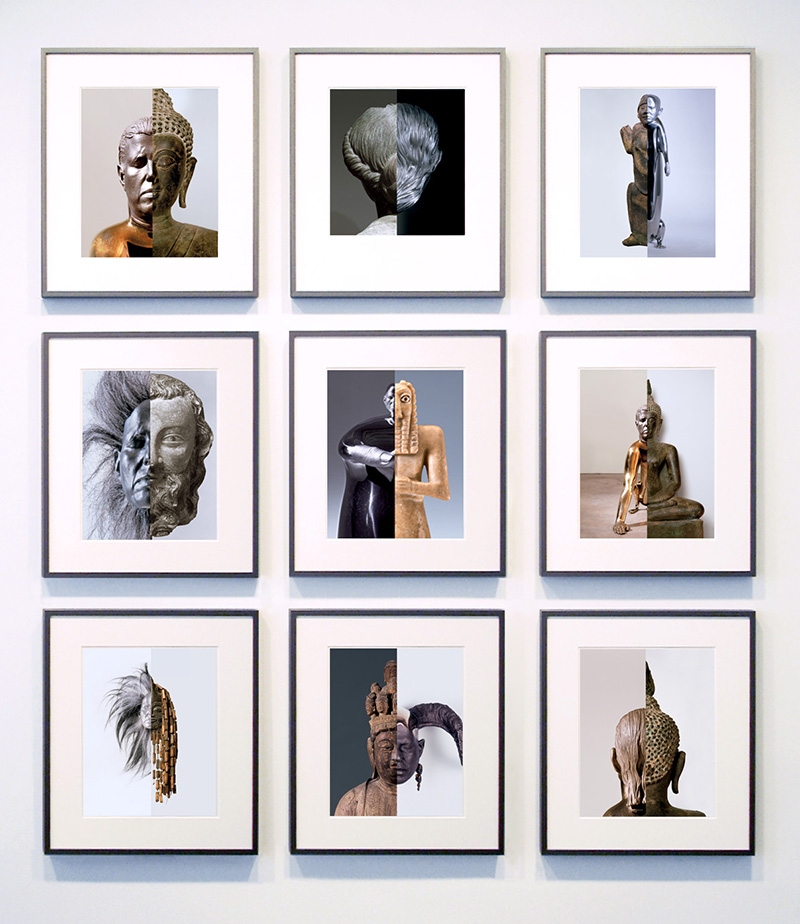

On the way down the stairs to UMOCA’s Main Gallery is The Metamorphosis of an Object, a series of prints by Pondick that features neatly spliced-together images of sculptures—Pondick’s Dog with the Seated Buddha in Maravijaya, for example. It’s a direct tie between Pondick’s own sculptures, which meld together otherwise incongruous body parts, and an ancient fascination with the human figure. In Pondick’s Dog, the yellow-stainless-steel figure is perched back on its canine hind legs, but its front legs are human arms, large and outstretched. These smooth, chrome-like arms extend into a pair of remarkably intricate human hands, which lay planted on the floor. At the top is a detailed head crafted from Pondick’s own likeness: eyes closed, hair slicked back, mouth downturned at the corners.

In melding animal bodies with her often exhaustively precise human components (made through life casting or 3D scanning), Pondick’s sculptures bring an element of the hyperreal into the surreal. When we look at art, we often instinctively search for connections, things to which we can relate. Pondick recognizes this tendency to search for artworks’ distinctly human elements, and she embraces it, toying with the human form and the psychological themes it evokes in her audience. Her resulting sculptures are at times fantastical, at times unsettling and thoroughly difficult from which to avert your gaze. Unlike Dog, both Muskrat and Wallaby present the animal body as the largest component of each sculpture, making for a more whimsical and amused first impression. The two statues stand on their back legs, tails stretched out behind, with tiny human heads. In Muskrat, the rodent’s front legs fold into human fingers. In Wallaby, the arms—one human, one wallaby—hang heavily, so much so that they feel almost lifeless.

Other sculptures bring viewers more immediately into the realm of the disturbing. Prairie Dog, for example, looks more like a three-fingered human hand with a massive, bulging growth than a prairie dog’s body. With Mouse, we see a couple of tiny rodent legs, hidden underneath a human head that rests on its left ear—the head’s sleek hair is pulled down into a small curl, like a mouse’s tail. From certain angles, though, Mouse looks more like a single human head, stripped of its body with the exception of a few strange ligaments extending from the nape of its neck. And then there’s Marmot, which looks almost like a misshapen human infant. The marmot body lies close to the floor, prostrate, arms outstretched. One arm extends into an adult-human hand; an adult-human head rests with its right ear on the ground.

For the most part, Pondick doesn’t disguise the stainless steel, the carbon steel or the silicone rubber that she uses for the sculptures exhibited at UMOCA. The material of each piece, paired with each figure’s purposeful positioning, feels weighted. There’s something transgressive and powerful in seeing how immovable Pondick’s body is when so flawlessly infused with animals’. In fragmenting and distorting the human body, Pondick’s work reminds of Louise Bourgeois’ figural and corporeal sculptures. Both emphasize the power of bodily positioning and gestures, although Pondick’s works on display here are less explicitly emotionally laden and aggressive than are some of Bourgeois’.

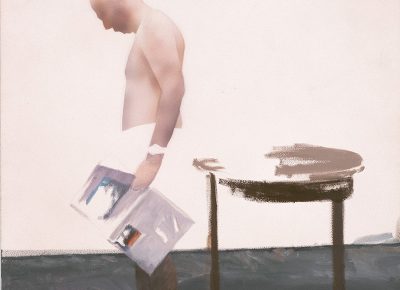

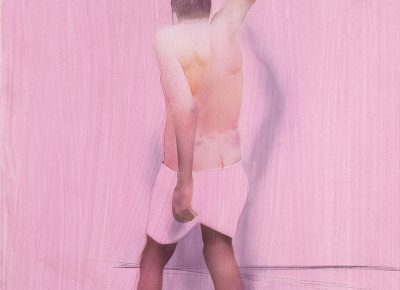

Like Pondick, Feintuch maintains that fixation on the human body: its gestures, its presence and posture, its size and distortion, its extremities (hands and feet, especially). He also uses his own body as a model for his work. When viewed next to Pondick’s work, however, Feintuch’s 11 paintings feel light, almost weightless, and there’s something deeply alive about them. He plays with myth and a bit of caricature, and he uses a lot of bright or pastel colors: blue skies, white fluffy clouds and, especially, the orange-to-white pinks of flushed skin.

Pondick neutrally positions her hands, laying them flat against the floor or hanging them limply, but she sculpts her hands into expressive detail. Feintuch, on the other hand, finds bodily expression through movement and action: flexed feet and toes, white-knuckled hands, posed fingers. Feintuch plays with myth and caricature, too: In Legs Up, Feintuch paints a long and thin figure in the sky, covered up mostly by clouds except for two lanky legs that stick straight up and an arm that rests horizontally against a cloud with a single finger pointed downward. It’s funny, ironic and almost subversive: It’s some sort of godlike figure, living in the sky, finger pointed, perhaps to instruct or declare—but it’s also got those cartoonish legs. Another Assumption has someone with their head and body in the clouds, feet peeking out the bottom; Over the Hill has giant legs reaching up to the sky from behind a grassy green hill.

All of Feintuch’s figures have their faces turned away from the viewer, as though inviting us to watch for longer. In Bacchus, Seated and Two-Fisted, Feintuch paints his figures naked, with massive and broad, pink backs, hunched toward a small, gray-haired head. In each, a spindly hand holds fruit: a bunch of grapes and a single cherry, respectively. Fat Hercules depicts a similarly naked, massive body, but here, Feintuch’s subject is standing. It reminds of the ancient Farnese Hercules statue, which depicts a mighty yet weary Hercules as he leans on his club. Feintuch’s Fat Hercules leans on two crutches: one against his left side, the other propped up against his lower back. In his right hand, he carries a club—unlike Farnese Hercules’, Fat Hercules’ club appears small, almost deflated. It’s surprisingly tender, because however powerless Feintuch’s Hercules might appear, he still signifies and imparts something inexplicably powerful. There’s something personal in each of Feintuch’s somewhat self-deprecating depictions of himself, particularly in his full-figure paintings: The action and movement of Knock Out, the solemnness and solitude of Standing with Newspaper, the unfinished element of Arm Up. Then there’s the more brightly and passionately pink Rabble (II). Here, Feintuch’s figure has one leg stepping forward, his right fist raised in the air. Like Fat Hercules, Rabble (II) stands out from the uncertainty otherwise exuded by Feintuch’s figures, presenting instead an unexpected power—here, a power that feels determined and defiant.

Both Feintuch and Pondick imbue suggestiveness and metaphor into their art, but they leave it entirely up to their audience to contemplate the themes that their work evokes. While the narrative that emerges from Feintuch’s work isn’t exactly a self-portrait, it does visualize major, human topics for its viewers: life and death, strength and weakness, power, aging. With her sculptures, Pondick confronts viewers with the sheer, psychological impact of the human body—its material, form, positioning and hybridization.

Pondick and Feintuch’s works emphasize each the physical and the psychological, incorporating the mythical and marvelous while remaining deeply tied to what makes us human. On view at UMOCA through July 15, Heads, Hands, Feet; Sleeping, Holding, Dreaming, Dying is a mesmerizing exhibition that commands more than one visit.

For more information, visit utahmoca.org.