David Baddley: Finding the Line Between Nature and Self

Arts

David Baddley has little life without photography. Currently, his full-time position as head of the Photography Department at Westminster College keeps his day-to-day fully engaged with the artform. In a grander sense, photography has been with Baddley for most of his conscious existence. His father gave him a Polaroid camera in early elementary school, and he immediately fell in love with the unique processes, practices and ideas inherent in photographic art. “I remember wondering if it was possible to actually catch the moment at which I made the picture,” he says, yet unaware that such was, in fact, the only moment you could capture with a camera.

This inquisition led Baddley to his first-ever photo experiment, in which he snapped a photo of himself in the bathroom mirror and ran out of the room to see what image would turn up in the developed photo. The result? “This big blinding flash with these two little legs sticking out of it,” he says. “I was delighted.”

This anecdote does more than illustrate Baddley’s early interest in photography as a medium. It shows how, even in the very first photos he ever took, some of the crucial themes that define his work today were already present. “That idea of perception, and exploring the nature of perception, is probably the one thing in common with all the work that I make,” he says. “Not being a religious person, I believe that it is through perception that we literally create reality for ourselves. Therefore, at least from our own perspective, we create the universe as we experience it.”

“I believe that it is through perception that we literally create reality for ourselves.”

Baddley’s careful manifestation of technological forces in his work furthers this vision of an unstable reality. In December of 2016, Baddley installed a video piece in an empty Gateway storefront featuring footage of the roving ocean waves. As opposed to a straight-on shot, he tilts his camera at a dramatic angle. Mathematically, this diagonal presents the ocean in its grandest form. It’s through this tilt that the longest stretch of shoreline is visible through the installation. “I’m trying to compose the image in such a way that it acknowledges the technology that’s capturing that,” says Baddley. “The experience is not only based on my desire and my presence, but it’s also based on what the technology is capable of and what it’s not capable of.”

This installation introduces another key tenet of Baddley’s photography: the questioning of humanity’s relationship with the natural world. As a lifelong Utah resident, Baddley sustains a love and respect for the natural wilderness around us, but also retains a potent skepticism about how we truly interact with and relate to such spaces. Baddley turns away from photography in the ilk of Ansel Adams, which he sees as dishonestly presenting the true exchange. In particular, Baddley disagrees with “this kind of attitude that human beings don’t belong in the world.” While he acknowledges that “certainly we’ve done a lot of things to suggest that maybe we [don’t],” his own art seeks to explore a more symbiotic connection between ourselves and the world around us.

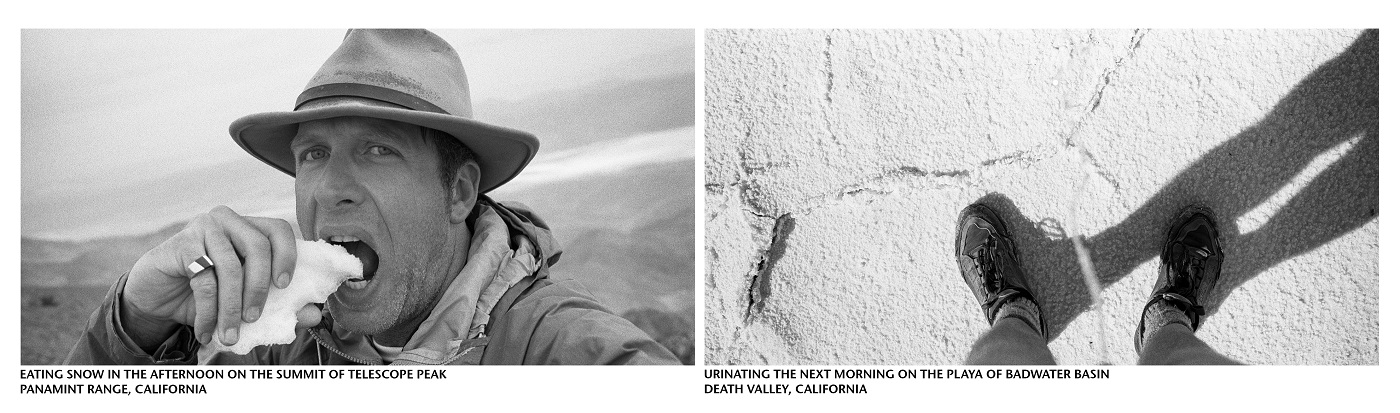

As in the installation at The Gateway, Baddley presents a more nuanced exploration of what it means for us to look at a photograph or video of nature. “Part of the human condition is that we are of the land; we are of the air; we are of the water; we are of nature. At the same time, we’ve come to live in a way that sort of separates ourselves from it,” says Baddley. In his performance works in particular, Baddley will often exaggerate this skewed sense of belonging. One diptych presents the artist eating a mound of snow from the top of a mountain, then urinating (presumably) that very same water back onto the land the following morning. “By involving my own action and my own body, I was questioning my role and including myself [in nature],” he says.

“Part of the human condition is that we are of the land; we are of the air; we are of the water; we are of nature.”

A recent example of these artistic and ideological explorations comes through the work displayed here, a series of 11 monochromatic photos taken in Deer Creek that display a thick, imposing web of brambles and branches. “The subject of them all is nature, but it’s not beautiful landscape photography,” says Baddley. “It’s almost more like calligraphic drawings. It does explore the technology because I’m playing a lot with hardness and softness that is kind of a manifestation of the technology [of the camera].” Specifically, Baddley used a Leica Monochrome camera, a digital device that forgoes the special optics necessary to process color, giving each of these images a black-and-white, palpable crispness.

While these photos initially appear simplistic, the hard/soft divide reveals layers and layers of interconnected lines and divergent paths. The ultimate effect mirrors looking down upon nighttime city lights from a plane window—at once the most distanced and holistic view you could possibly take of the subject. Baddley describes these desert flower stems as “lattices,” saying that, “There’s just enough of a difference in focus [between the layers] that your eye catches focus of those thin, little white lines, and the rest of it kind of goes back and forth as to whether or not your eye or even your mind want to resolve it as location, pattern, texture or background.” These still works may seem more obscure and less direct than Baddley’s performance or video work, but they explore his key themes of perception and self with equal potency.

Through Baddley’s stark, minimal work, the viewer encounters a worldwide disconnect in real time. While nature and reality exist in these photos, the “true” image always seems just out of reach, obscured through the human/technological screen of photography. Find more of David Baddley’s work through his website, davidbaddley.com, and undergo your own exploration of this messy tangle of human, art, technology and nature.