Seven Masters: From Ukiyo-e to Shin-hanga

Art

In the early 20th century, Japanese woodblock prints—which had fallen out of style—made a resurgence. It was a new era, so not only was there a modern life to capture in the classic style of ukiyo-e, but there was also money to be made in revitalizing this old style. Like many countries, Japan was going through a period of industrialization, and the Western hunger to consume and influence the world was growing rampant. The creatively and financially lucrative moment became a movement known as Shin-hanga, which translates to the “New Print.”

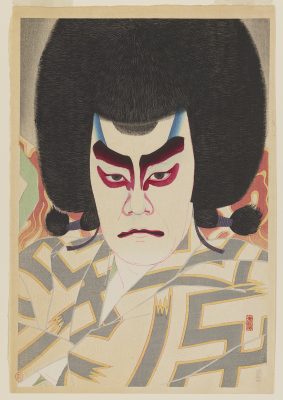

Utah Museum of Fine Art’s Seven Masters exhibit puts the new prints in context of the seven artists (and their publisher, Watanabe Shozaburo), who defined the resurgence. A big difference between the ukiyo-e and Shin Hanga periods of Japanese woodblocks is exclusivity. Rather than mass produce prints from any artist, Shozaburo enlisted specific artists who could recreate the classic method while incorporating modern techniques and tastes (like oil painting), then published only a small run to enforce scarcity and create value. Each of the seven artists brought something to the table the others couldn’t quite. The exhibit separates each artist’s work to give a sense of this contribution, as well as the story behind each artist that led them to their participation in the movement.

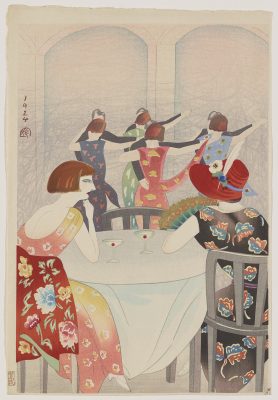

Shin-hanga started in 1915 when Shozaburo published “Umbrellas” by Friedrich “Fritz” Capelari, an Austrian painter who had been working on his own, creating watercolors and portraits that drew on his time in China, Java and Japan. Shozaburo considered Capelari to be an ideal collaborator because of his foreign sensibility over the Japanese style. Surely, it would attract a tourist’s purse. “Umbrellas” shows a line of people walking away from the viewer, shrouded in traditional umbrellas (wagasa) with color evocative of the ukiyo-e style.

“Each of the seven artists [featured in Seven Masters] brought something to the table the others couldn’t quite.”

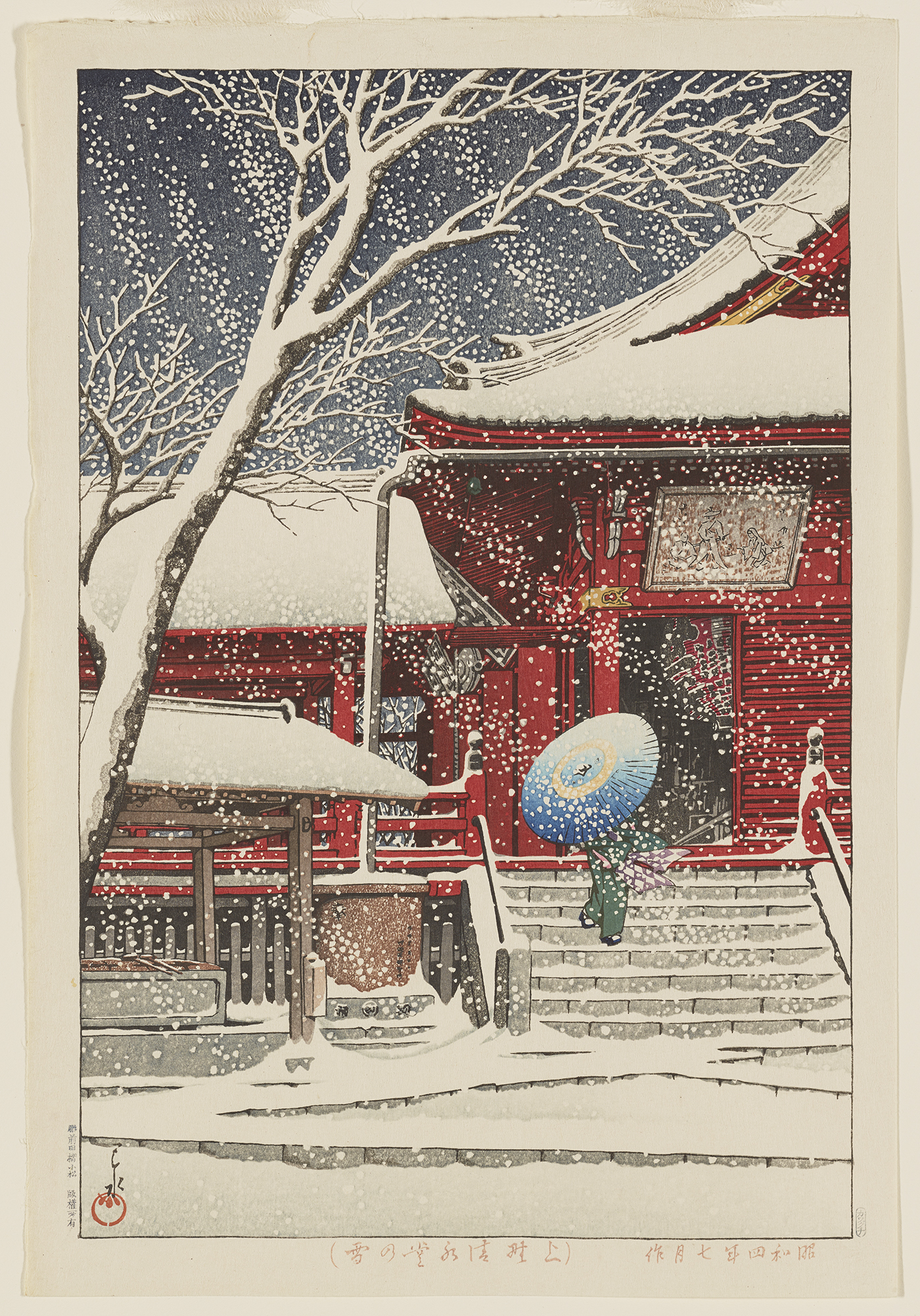

Capelari’s work was a catalyst for Shozaburo’s interest in producing Shin-hanga. The seven artists who comprise the brunt of the movement were Japanese men, each with their own story. For instance, Kawase Hasui was the most prolific print artist of his time and designed more than 600 woodblock prints. He struggled to chase his passion for art early on, as his family wished him to head its business of manufacturing and selling braided silk cording. After a successful run showing his landscape print series, The Eight Views of Lake Biwa, Hasui showed his work to Shozaburo, and they took off. More than five hundred were published over the course of the century. Hasui was apparently picky about the kind of landscape he chose to depict, and you can see it in his work where he emphasizes odd incidents of nature and society: a bend in a forest path, a small fishing dock on a rainy day, a boat nearly obscured by fall leaves. His lines are crisp and thick where needed, thin and subtle where not. When you leave this Seven Masters, Hasui’s work may become your definitive mental image of Shin-hanga.

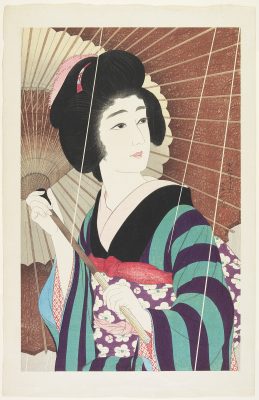

But there’s quite a range, and not all of Shin-hanga was influenced by the market that Shozaburo stirred into being. Take the work of Hashiguchi Goyo. His taste sat between Eastern and Western traditions, making him an ideal collaborator for Shozaburo and the movement, but in 1915, after Goyo made Woman at the Bath for Shozaburo, he discontinued their partnership (Shozaburo supported this) to self publish and pursue printmaking as his interests dictated. Goyo’s prints were some of the highest quality. Girl in a Summer Kimono shows Goyo’s ability to reproduce the quiet nature of cloth folding in on itself. Seven Masters shows much of his work focused on women, though he also explored landscapes, as he was inspired by travel within Japan.

“Japanese woodblock prints are immaculate renderings of a world that we, as a Western audience, have little connection to.”

As interesting as it is to see the Shin-hanga movement in context of the artists who defined its popularity, it’s important to recognize the court of influences that led to the final product of any one print. Beyond the artists are the publisher (most often Shozaburo), designer, carver, printer, potential buyer and sometimes a patron who subsidized the print. Each of these people had a say in the design according to their investment, and while it’s a reality of so much art (especially those that make it to gallery), there’s something about Japanese woodblock prints that make one want to forget this fact. They are immaculate renderings of a world that we, as a Western audience, have little connection to, and it’s tempting to imagine the prints existing as exotic works of passion in a vacuum.

Seven Masters balances this temptation by always reminding us of the influence of Shozaburo in each of the seven artists’ lives. The “market” he created dictated the movement in soft and hard ways via influence and direct financial support. This reminder is combated by just how lovely each print is despite a wholly individual approach. Ukiyo-e was always a group production, after all—the Shin-hanga movement is instructive in how it displays the beautiful final work without hiding the story of the material conditions that enabled it.

You can visit the Seven Masters exhibit at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts through April 26. More information is available at umfa.utah.edu.