Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood: Sunset Baby

Art

Dominique Morisseau’s Sunset Baby is a heartfelt, timely and at times untamable play that explores questions of reconciliation: of morality and principle, of the movement and its individuals, of saving and savoring the world, of freedom (or “No fear,” to go by Nina Simone’s definition) and how to attain it.

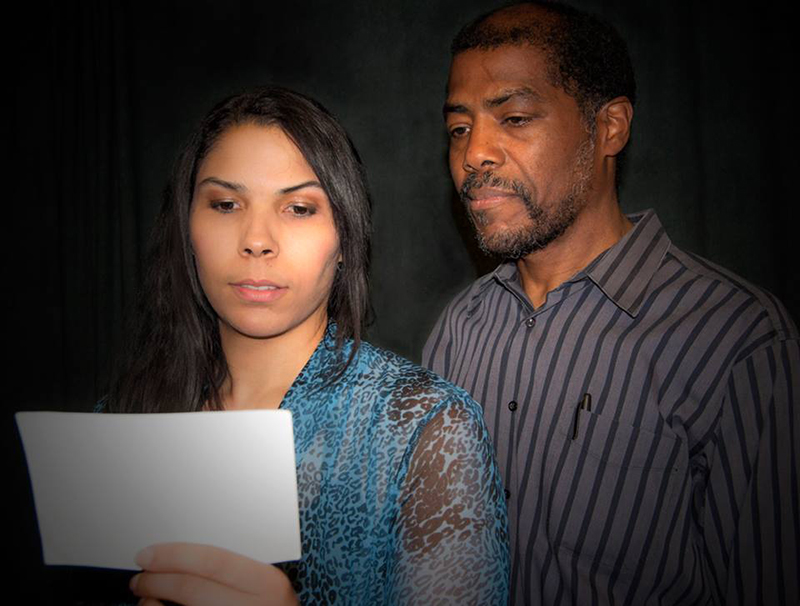

At the center of the play is Nina (Michaela Johansen), a headstrong, knee-high-leather-boots–wearing, nigh-impenetrable drug dealer who does what she needs to survive, but dreams of leaving the hustlin’ lifestyle for a quieter one—one where, everyday, she could see the sunset. Her now-deceased mother, Ashanti X, was a famous activist who died a crack addict, leaving Nina only with a stack of letters written to her absent father, Kenyatta Shakur (William Ferrer), a black-revolutionary-made-political prisoner due to his radical and sometimes militant activism. The letters are highly sought after, proving themselves both monetarily and historically valuable, and the play starts when Shakur, recently released from prison, tries to reconnect with Nina—whom he hasn’t seen in 20 years—and asks to see Ashanti’s letters.

Nina is resentful of her father, refusing even to grant him the privilege to call her by her name, and believes that he chose a failed movement, an impossible cause, over his family, leaving a loving wife and young daughter behind. Johansen’s Nina is unforgiving and unapologetic, a woman who trusts no one—shutting out even her loudmouthed but articulate and charming boyfriend, Damon (played energetically by Calbert Beck IV).

The play attempts to ground the political in the personal. Nina and Damon are street hustlers, although Kenyatta and Ashanti’s main cause in the ’70s and ’80s—anti-disenfranchisement—was dismantled by police violence and the government’s introduction of crack into black communities. Fatherlessness pervades as a motif, and increasingly, parallels are drawn between Kenyatta and Damon: Kenyatta, who felt that personal and familial intimacy would lead to a more vulnerable movement, and Damon, who speaks fondly of his 7-year-old son but vindictively of his son’s mother. Damon is spirited and talks nonstop in a familiar, sometimes babbling vernacular, though he still manages to throw in such scholarly references as Steven Spitzer’s Marxian theories of “social junk” and “social dynamite”: those who have fallen or jumped through the cracks of society and are now either dependent on others (“junk”) or will potentially rebel over this sociopolitical failure (“dynamite”).

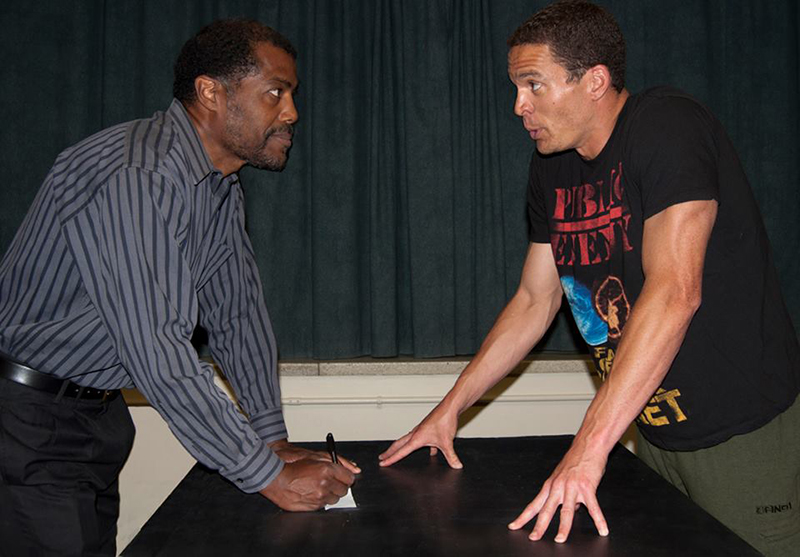

Set entirely in Nina’s small apartment, director Richard Scharine’s Sunset Baby is intimate and acerbic, swerving from spells of silence to fiery and spirited exchanges.

Because Sunset Baby’s most riveting storyline is in Nina’s relationship with her father, certain scenes involving the chattering Damon and the steely Nina felt drawn-out, repetitive and, at times, random. The long silences, however, were immensely compelling and where Johansen shone most: putting on or taking off her wig, applying makeup, stowing away her money, scowling, crying. Throughout, various songs by Nina Simone (another black—and artistic—revolutionary who made sacrifices in the name of a movement) play, and Simone’s impassioned voice, a velvety force, is a lush and unyielding addition to the stage.

Rather than necessarily providing insight into the individual consequences of revolution and radical activism, Sunset Baby chooses to focus on this particular father-daughter pair, and the inscrutability and defenselessness of love—something that, out of self-preservation, neither Nina nor Kenyatta allow themselves to indulge in. The most successful moment when Morisseau integrates personal and political, however, is also the most powerful. Ferrer is the most affecting of the three actors: His Kenyatta carries himself with a subdued conviction, speaking haltingly but movingly, as he records his spoken love letters to Nina. He speaks for an entire generation of black revolutionaries as he explains that he never expected change in his time—“It was all for you, Nina.”

By Dominique Morisseau (2012); directed by Richard Scharine; set design by Dan Christensen; lighting design by Glenn Linder; costume design by Linda Moon. A production by People Productions, presented at Sugar Space Arts Warehouse; peopleproductions.org. With: Michaela Johansen, William Ferrer, Calbert Beck IV.