Levi Jackson Explores Illusions in the Promised Land

Art

Gritty, dark and suffused with a subtle, surreal humor, Levi Jackson’s photographs play on the illusions operating in the Western American landscape and culture. From a black-and-white image of the ground stamped with the phrase “My Name Is Mud” (Untitled, 2014) to a series of photos featuring livestock decoys and other objects wrapped in fabric (including Ms. September, 2014 and Hey, Pilgrim, 2019), Jackson isn’t shy to intrigue viewers with simple but perplexing combinations of objects and media. “What I am trying to do is create something that isn’t harmonious … but which still tricks you into thinking it’s true,” Jackson says. “This is the ideological foundation of the West … and of photography.”

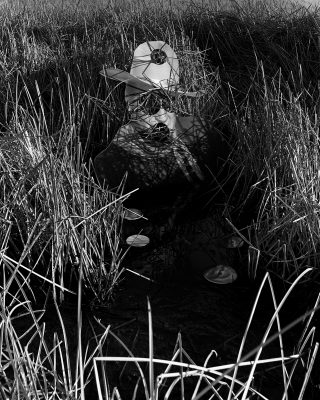

Jackson’s roots in the West instilled a fascination with the Western landscape from an early age. “I grew up in Utah and spent a lot of my childhood driving around the desert and exploring. I became really fond of the grittiness of this place that is often crushed by the Bierstadt-billboard-esque portrayal,” says Jackson. “But there is this blind dedication to it being the ‘promised land’ or something … which it is. I love it, and it scares me.” His photographs are often monochromatic and pull from this childhood observation. One photo Bushwacker (2015), featured at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, captures the mystery and optical illusions that provoke a child-like wonder in the desert. In the image, a coyote carcass floats over a sun-baked field, dark mountains rising in the distance. But Jackson’s photography and his approach is also influenced by his time on the East Coast and the contrasts he saw between the two landscapes and cultures.

“There was this equivalent in their mind between the wild expanses of the west and a planned city park.”

When Jackson moved to Brooklyn to earn an MFA in photography/sculpture at the Pratt Institute, the stark contrast between the uninhabited expanse of the West and the bustle of New York City was a challenge. He felt blocked by the radical shift and the crowded skyline. “When I first moved to Brooklyn, I was really hurting,” says Jackson. “I couldn’t work outside … too dense. It was terrible. I remember talking to my advisors, and their recommendation was to work in Central Park or Prospect Park.”

Coming from Utah, where broad expanses of desert and mountain passes are a stone’s throw from any sort of crowded civilization, the idea that Central Park could cure his creative ills shocked him at first. “It was amazing to me that there was this equivalent in their mind between the wild expanses of the west and a planned city park.” But experiencing the differences, he says, made him see his home state with new eyes. Coming back to Utah after his graduate program, he started exploring the ways the landscape and culture are suffused by illusion, making him realize that any place you think you know well, especially the mythologized West, can play tricks on the eye and mind.

Jackson uses his art to explore place narratives and how people assign meaning to objects, especially by dismantling the grandiose narratives we have of the “American West.” His newest project draws inspiration from the pioneering linguist Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics, which classifies and unpacks the ways that humans attach meaning to things. Because Jackson is teaching at BYU and Weber State University, he says he has more time to dive into the conceptual foundation of his work. Jackson says he’s looking at “the connection between what Saussure argues is the structure of signs, the way his lectures were compiled into this canonical text and the way we interpret his text 100 years later—in a different place, in a different world, with different technology. He uses a line drawing of a horse. I use a digital photograph of a 1996 Ford Mustang.” This analytical approach gives his images depth even in their straightforwardness.

“I have a new ethos, which is to just make art out of things that I want to own or be around.”

But Jackson is also passionate about making multi-media sculptures, which are often the subjects of his photographs. Lately, he’s been exploring technology and interesting objects a person might not consider “sculpture.” He says, “I have a new ethos, which is to just make art out of things that I want to own or be around, a sort of neo-capitalist nightmare or something. I just bought a computerized sewing/embroidery machine. I am going to tell it to make a bunch of designs on T-shirts and other objects based on the limitations of the ‘brain’ in the sewing machine (80 embroidery designs, 103 stitches, six fonts). I like the idea of this industrial machine just cranking out designs that the machine has … pre-programmed and [has] pre-determined that I will like.”

Jackson’s work balances conceptual and technical approaches, levity and weightiness of subject with the grittiness of Western heritage with the polish of New York schooling. With a bevy of teaching, shooting and crafting on Jackson’s docket, chances are you will see his frank images and sculpture increasingly around Salt Lake. In the meantime, you can check out Jackson’s work online or on his Instagram account, @levi.jackson.