Jamie A. Kyle’s Transfiguration of the Commonplace

Art

Salt Lake City–based photographer Jamie A. Kyle’s work is, in her words, the result of “gathering”—lots and lots of it. Her compositions are populated by an eclectic assemblage of found objects that are nearly universally unassuming and small enough to fit in the palm of one’s hand. In one photograph, A single light. . . (2014), Kyle illuminates a forest composed of what could well be the forgotten contents of a miscellaneous household drawer. These are odds and ends, lovingly gathered: model trees mingle with sewing pins, a threaded spool, nails, buttons, as well as several game pieces—a die and some jacks. They are self-contained worlds seen up close, Whitman’s “multitudes” magnified for the human eye. In contemplating them, the viewer navigates two conflicting impulses: whether to see them as discrete objects embedded in a network of associations and memories, or as purely formal in nature, a sensuous play of surface, material and form. In other words, is the aforementioned jack more a referent to the world of child’s play, or is it a purely visual phenomena, the glimmer of metal as it unfolds in three dimensions?

“I often think about when I was a little kid, how anything could become entertainment, how any object could become something unique and special.”

These photographs are still lifes. As such, they belong to a genre that is as old as the ancient Romans. In a book tellingly titled Looking at the Overlooked, art historian Norman Bryson distills the essence of the still life as rhopography. That is, “the depiction of those things which lack importance, the unassuming material base of life that ‘importance’ constantly overlooks.” Kyle’s photographs are nothing if not an exercise in rhopography, the elevation of the everyday and the mundane. Coins and lightbulbs take center stage, as do wine corks and spoons. To explain her fascination with the materials of daily life, Kyle, who first studied photography at Weber State University, and who pursued an MFA from the University of Utah, recalls her childhood.

“I often think about when I was a little kid,” she says, “how anything could become entertainment, how any object could become something unique and special, how any corner or space could be turned into a secret fort.”

Kyle’s photographs and scans are created in a controlled setting. Of her process, she says, “I have a big, empty table where I’ll set things next to each other, experiment with combinations, move things around. Next, I photograph and scan everything to get them into Photoshop. From there, it’s round after round of Photoshop—lots of layers, lots of edits.”

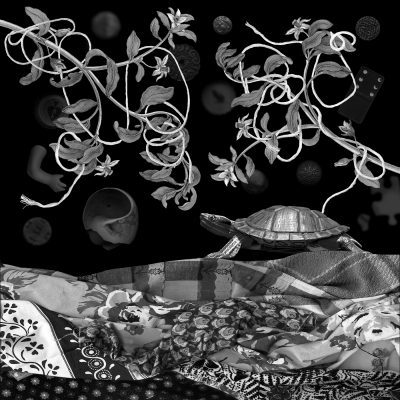

Like many of the great practitioners of the still life, Kyle employs the technique of chiaroscuro, the strong interplay of light and dark, to great effect. Often in her photographs and scans, light will act as something of a guide, a welcome guide that draws the viewer’s attention to a particular focal point, mapping a way through a dizzying maze of the material. In Kyle’s words, “It makes each photograph a sort of hunt,” with “lots of small things or dark spaces to be discovered.” Moreover, Kyle uses light to inflect her compositions with a sense of tactility, an attention to the realities of texture. Several centuries ago, the Spanish master Juan Sánchez Cotán did much the same, using light to illustrate the contours of materiality in paint far beyond the capabilities of the naked eye.

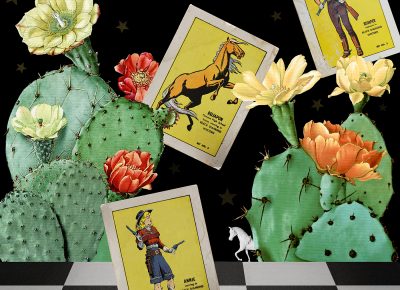

Part of what makes the still life so powerful, contends Bryson, is its utter absence of human presence and touch, its eschewing of the animate in favor of the left behind. This absence of the human is pushed to its boundaries—but never broken or violated—in Kyle’s work. Her work seems almost always to return to the representation of the human: whether in the form of a photograph of two smiling brothers tucked in her Things found following… series, or the presence of toy soldiers in Found Object Still Life, awash in a sea of vibrant cloths. One is struck by how small they are. It’s hard to resist reading this impulse as anything less than a corrective to portraiture, an acknowledgment of the material realities of our lives.

“It makes each photograph a sort of hunt [with] lots of small things or dark spaces to be discovered.”

There is an enigmatic, and perhaps pleasantly unsettling, quality to Kyle’s assemblages. Collectively, they appear suspended outside time and space; yet taken discretely, they belong to a particular moment and place. They offer glimpses of objects—a photographic portrait, a scarf, the pages from a book—that are rich repositories of history and memory, but decontextualized, their full wealth of meanings is inaccessible to the viewer. Their fundamental unknowability is their immediate allure and renders them sobering. Rather than aspire to historicity, they embrace a furious eclecticism in which the crispness of the image cuts sharply through to assert the immediacy of direct experience.

Kyle’s approach requires her to be a curator and a collector as much as a photographer. She speaks of “finding things in drawers, garbage cans, thrift stores, antique shops, books, my own living room, on the sidewalk, etc.” This process of salvaging and reappropriation cues us into another art-historical precedent—the Wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities. In the early modern world, they were assembled to act as visual testaments to the marvels of the empirical world and as material signifiers of the taste and worldliness of their owners and creators. More contemporary practitioners, among them Joseph Cornell, have fashioned them as sites of enchantment made of the stuff of everyday life. The ordinary rules of association don’t apply.

“I specifically noticed it broadened the types of artists I met; people with practices, techniques, backgrounds and visions very different from my own.”

In addition to maintaining her own artistic practice, Kyle is active within the Salt Lake artistic community at large. Notably, she was involved in the founding of the Downtown Artist Collective (DAC). A cooperative run by artists for artists, the DAC fosters a spirit of collaboration and communication between local creative types. “Working with the DAC has been a dream,” says Kyle, “because of all the artists it put me in contact with. I specifically noticed it broadened the types of artists I met; people with practices, techniques, backgrounds and visions very different from my own.”

The great philosopher of art Arthur Danto memorably termed the project of much post-war art as nothing less than “the transfiguration of the commonplace.” It is to this tradition, as much as any other, that Jamie Kyle belongs.

You can find Kyle’s work at her site, jamieakyle.com, and in a new zine by Torpor House called Grayscale, here.