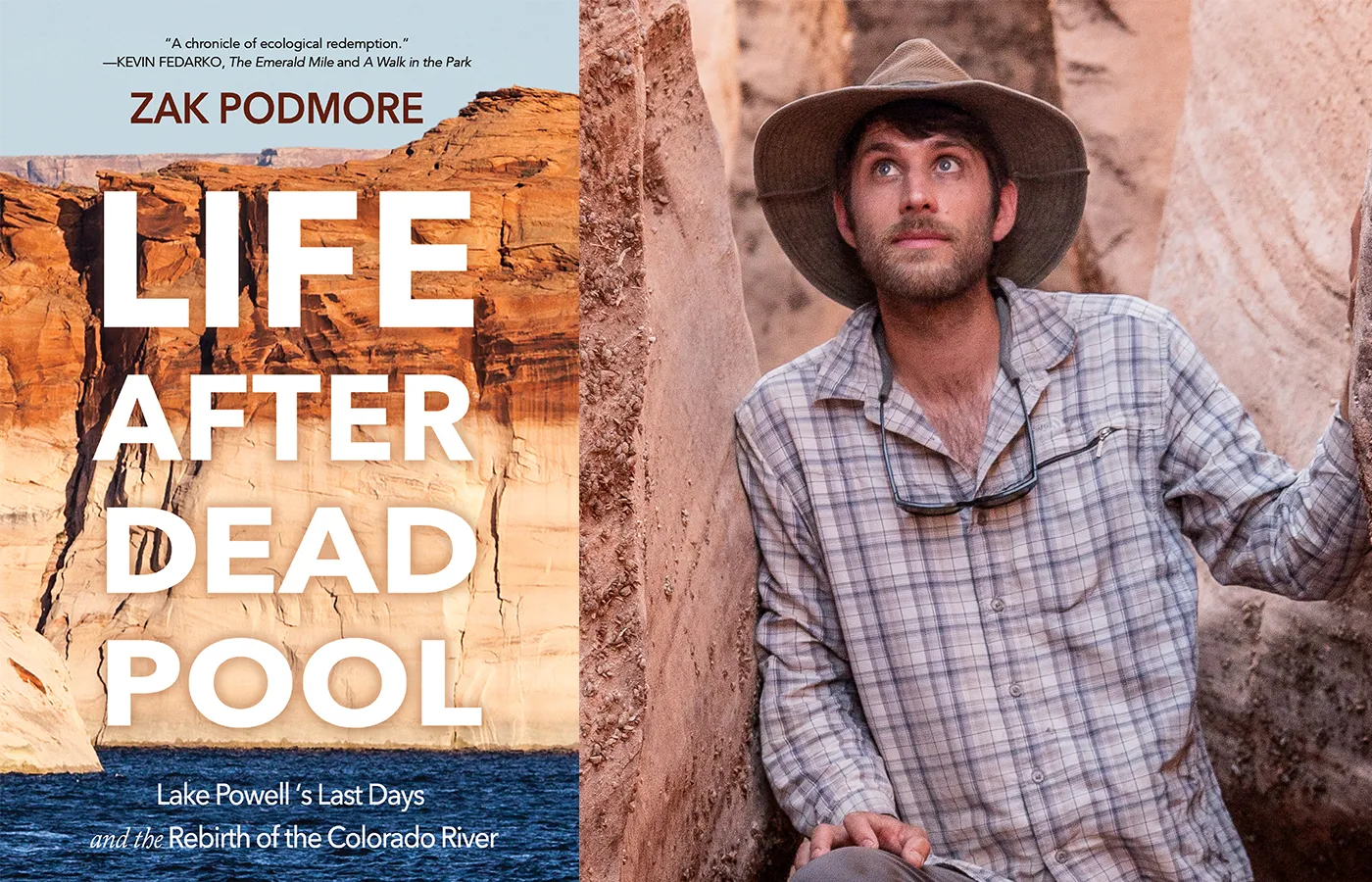

Water and Rebirth in the West: Zak Podmore’s Life After Dead Pool

Arts

Zak Podmore grew up hating Lake Powell. The son of a pair of raft guides, the Colorado native was raised on anti-dam books like Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang—which he calls “Abbey’s finest young adult novel”—and Eliot Porter and David Brower’s The Place No One Knew. These books mourned the death of Glen Canyon, the stunning, spiderwebby network of red rock flooded by the Glen Canyon Dam’s construction.

In 2011, Podmore made it to Powell for the first time paddling the Colorado River. There, he was confronted by still waters and flats of unstable “Dominy Formation,” a paddler/environmentalist colloquialism for the piles of silt left by the dam. “Dominy” is named for Floyd Dominy, the Bureau of Reclamation commissioner who ordered the dam built. After stepping out of his kayak and sinking knee-deep in the muck, Podmore’s opinion on the dam was not changed.

“I wan[ted] to bring environmental writing into the twenty-first century as much as possible.”

Podmore returned to Powell in 2021 with the Glen Canyon Institute’s Returning Rapids Project. While cataloging the Millennium Drought’s lake-draining, Podmore was shocked: “Probably the biggest ecological recovery in the history of the Southwest was already underway,” he remembers, “and I hadn’t heard anything about it.”

Ironically, Podmore refers to the effects of the drought. As Powell recedes, thousands of acres of habitat and cultural sites buried by the reservoir have resurfaced. Seventy years of submersion prevented invasive species like Russian olive from taking root, while the return of the flash flood cycle cleared out the Dominy. As an environmental journalist, Podmore was excited to break the cycle of green doom and report something positive.

Podmore’s Life After Dead Pool covers the past, present and future of Glen Canyon and Lake Powell. “There’s something that wasn’t really acknowledged in most of the white environmental literature of the 1960s,” says Podmore. “I wan[ted] to bring environmental writing into the twenty-first century as much as possible.”

The biggest examples of this are the Diné and Hopi, who were largely excised from the fight between the Bureau of Reclamation and the Brower-led Sierra Club about their ancestral land. While the federal government and white environmental clubs bargained over what to flood, the area’s indigenous peoples were treated as if they never were there at all. Podmore instead centers these perspectives alongside other stakeholders like economists, ecologists, historians and river rats as he travels up and down the canyon to understand the shrinking reservoir.

Podmore’s conclusion? “The Glen Canyon dam is on the brink of failure,” he says. “It’s threatening the water supply for the 27 million people who get Colorado River water downstream from the Dam.”

The Dam has edged ever closer to dead pool levels since 2000, the level at which the dam can no longer release water or generate power. The resulting blockage would cut off water for much of the Southwest and increase the amount of Dominy piling up, likely leading to a catastrophic break. Rather than despair, Podmore chooses to paint a bold new future for the Southwest.

“Probably the biggest ecological recovery in the history of the Southwest was already underway and I hadn’t heard anything about it.”

Drawing on the dam’s New Deal roots, Podmore engages with modern ideas of draining Powell via newly-bored tunnels and installing solar arrays to supplement power. States could harness the water of the freed Colorado and Glen Canyon could restore itself under an inter-tribal and federal coalition like the one governing Bears Ears National Monument today.

It’s a thoughtful sentiment and far more tenable than the current state of the Dam. In Dead Pool, Podmore reminds us that the federal government has a habit of making mistakes with Utah’s public lands. As we stand on the brink of another Trump presidency, he also reminds us that the planet will eventually correct those mistakes. The question is whether or not we have the strength to correct them ourselves.

Buy Life After Dead Pool and the rest of Torrey House Press’s collection anywhere books are (locally) sold or check it out at your local library. To follow the campaign to restore Glen Canyon, follow @glencanyon_institute on Instagram.

Read more interviews with artists:

The Anarchy of Dance in “Lake Bodies”

How the American West Shaped Dino Kužnik