Maguey Makes its Way: Wahaka Mezcal’s Journey Through the DABC

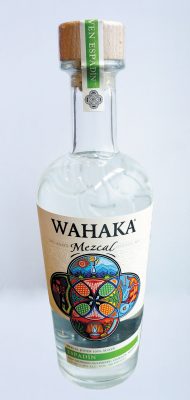

Art

Mezcal is a spirit made from varieties of the agave plant. It’s basically tequila’s cooler older brother. “Tequila was mezcal before it got the name tequila,” says Eduardo Belaunzarán, co-owner of Wahaka Mezcal, based in San Dionisio Ocotepec, Oaxaca, Mexico. “Tequila got the name of the terroir where it was made. That happened around 1900.” While tequila is only made with one species of the agave plant—blue agave—mezcals are made with many. “We know how to make alcohol with 40 different kinds of agave,” says Belaunzarán. “When you compare mezcals, you compare [them] like wine. Each agave will give you a different flavor.”

In the past, you could only get mezcal in Utah from a bar or by special-ordering a ton of it. But those dark days are behind us, friends. Introducing Francis Fecteau: bringer of new booze. “I am what’s called a wine broker,” says Fecteau. “I work on behalf of whatever winery or producer of alcoholic beverages wants to come to Utah.” His most recent success is bringing premium, handmade Wahaka Mezcal to the Utah market—the first consistently stocked and sold spirit of its kind in our state.

Belaunzarán first brought Wahaka to our market by contacting Scott Evans at Finca, and eventually had them and other joints like Bar-X and Copper Common special-ordering the product. But putting mezcal on liquor-store shelves for everyday consumers was another matter altogether. Fecteau worked with the DABC to get Wahaka’s joven mezcal into Utah for 18 months before making headway. “Getting stuff listed can be challanging,” says Fecteau, “but getting Wahaka listed was an important addition to include.” The process for deciding which alcoholic beverages will be sold in Utah has changed in recent years. In the past, experts like Brett Clifford would provide tasting notes and assess the quality of a product from the perspective of a consumer. A wine or spirit wasn’t judged only by its commercial potential but by its character, too. Last year, Clifford and a few other highly knowledgeable professionals retired from the DABC.

Without previous personnel like Clifford, communications from the DABC no longer rely on a taste assessment based in written-out notes, but rather by communicating enumerated beverage characteristics to ultimately accept or reject new alcohols. “Now it’s just a checklist: ‘not needed for this category or that category,’” Fecteau says, “just generic commercial-rejection reasons.” When the DABC said Wahaka Mezcal was “not needed in this category,” Fecteau assessed the situation. “Considering the existential ramifications of being ‘not needed’ in a category that didn’t exist,” Fecteau says, “I found it important to start a conversation about creating a category called mezcal.”

Without previous personnel like Clifford, communications from the DABC no longer rely on a taste assessment based in written-out notes, but rather by communicating enumerated beverage characteristics to ultimately accept or reject new alcohols. “Now it’s just a checklist: ‘not needed for this category or that category,’” Fecteau says, “just generic commercial-rejection reasons.” When the DABC said Wahaka Mezcal was “not needed in this category,” Fecteau assessed the situation. “Considering the existential ramifications of being ‘not needed’ in a category that didn’t exist,” Fecteau says, “I found it important to start a conversation about creating a category called mezcal.”

Fecteau contacted the DABC looking to address defining the category. Fecteau mentions that mezcal can incur reactions that underscore its exotic nature and its surprising contour for those new to this transcendent elixir. The only thing to do was submit another bottle and wait three months more. But Wahaka Mezcal was rejected again. So Fecteau called the DABC, but found that the spirit still wasn’t yet computing categorically. Recounting the back-and-forth, Fecteau concedes that the nature of mezcal may sometimes seem daunting, as it is a niche spirit that has only recently begun to gain popularity and momentum in the United States. “I persisted, and I said, ‘For years now, I’ve tasted this stuff: It’s fresh, it’s clean, it’s beautiful, it’s really well-made,” says Fecteau. “It’s a competently made and locally desired product.” He gave them another bottle and waited about five months, but faced rejection again.

After a year and a half of followup, Fecteau got through by emphasizing the obvious consumer demand for the product. Bar patrons consistently purchased the spirit, and thus bars needed a consistent supply. “I said, ‘Let’s look at this given that it’s a new kind of product: Maybe mezcal is misunderstood.’” says Fecteau. “I referenced two years of [Wahaka’s] special-order history. I used this information to emphasize the consumer demand and the commercial need to put the product on the shelf.”

Wahaka’s mezcal is just plain good. Some dusty plastic bottles on the bottom shelf at state liquor stores probably do taste strange, but the Wahaka joven (unaged) mezcal that I tasted was ambrosial. Beyond the normal smoky character of mezcal, an agave sweetness hits the nose. Earthy pepper bursts on the palate, and citrus follows in the finish. “We are keeping the traditional way of making mezcal,” says Belaunzarán. “We make mezcal like it was made 400 years ago.” He isn’t exaggerating. Check out the distillery tour on their website at wahakamezcal.com. There’s no modern technology in the process—just a group of Mexican mescaleros with machetes, outdoor firepits and burro-driven stone mills. It’s a seriously labor-intensive, time-consuming passion project that produces a complex, flavorful spirit.

Wahaka bottles five varieties of mezcal, some of which come from maguey plants (another term used for agave plants) that are aged up to 20 years before harvest. “It’s a lesser-known alcohol,” says Belaunzarán, “but it’s growing all [across] America—and the bartenders of Utah, they want it.” Based on my tasting, the people of Utah want it, too! Thanks to the labors of Belaunzarán and Fecteau, we now have it. Up next, Fecteau is working to introduce Wahaka’s reposado into our market. Meanwhile, give Wahaka’s joven a try. It’s something delicious—something different, something that hearkens to an age-old tradition of distilling.