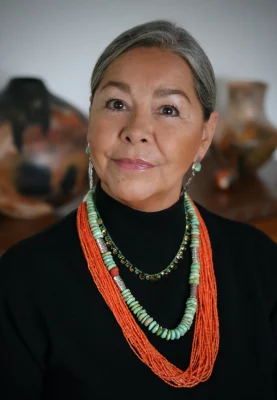

The White Buffalo Called Her to Clay: Pahponee’s Ceramics and Bronze Art

Art

It was when she visited a rare white buffalo and her calf that Pahponee really took her calling to clay pottery seriously.

“That white buffalo gave artistic assignments,” Pahponee says. “She started communicating with me in a way that I could see her image on clay. So at that moment in time, it was almost like watching a shooting star go across the sky. I knew exactly where I needed to go after that and what I needed to make. There was no more guessing at that point, and that’s what I’ve been doing ever since.”

It is now Pahponee’s 43rd year as a full-time practicing artist and her 10th year exhibiting at the annual Indigenous Art Market at the Natural History Museum of Utah, happening on October 12 and 13 this year.

As a member of the Kickapoo and Potawatomi tribes of the Great Lakes Region, Pahponee now lives in Nebraska with her ceramicist husband, traveling around the Southwest exhibiting at Indigenous markets with her clay vessels as well as their bronze casts, a medium she later found a calling to at a market in Arizona some 25 years ago. She has been with the same foundry, Bronzesmith in Prescott Valley, Arizona, ever since.

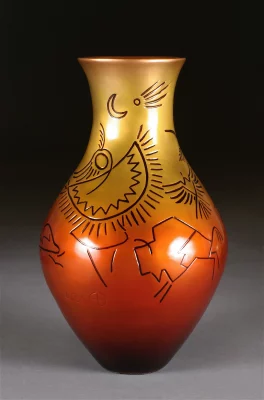

“It gave me the ability to express myself even more diversely as an artist,” Pahponee says. “For me, it gives me two different ways of looking at my designs.” She usually makes 25 special edition bronze replicas of her original clay creations, choosing pots that she feels would translate well into metal using the lost wax casting method.

“Passing information along to your descendants is [done] through storytelling, and art can tell those stories.”

She believes not every pot needs to be turned into bronze; the spirit of the work is best intact in its original clay form. Yet others—specifically ones with deep relief carvings of the natural world and her tribal ways of life—she believes make great bronze casts.

“That’s part of the storytelling, whether I want to talk about the Great White Polar Bear, or the birds that I’ve seen in my travels or about the White Buffalo. I find that the more carving that I do on a clay vessel, if we cast that and create a bronze from it, it creates a surface for the painting that’s very dimensional, carving it with a storyline that is important to me,” Pahponee says. “Passing information along to your descendants is [done] through storytelling, and art can tell those stories.”

She creates designs about her people’s connection to nature, how Native ideology centers the earth and the beloved non-human kinfolk indelible to Native culture, keeping alive the spirit of honor in ancestors. “I try to carve or draw or create in my pottery and bronzes how it feels to know that you’re related to all living things,” Pahponee says. “I draw petroglyphs because that’s the way the old people used to draw on the cave walls and the riversides. On some pots I put four different clan animals—or totem animals—to our Great Lakes culture that have helped us survive living outside all of these years.”

The visual pieces almost immortalize the stories to keep in remembrance forever, to keep them alive, baked into the sides of clay or bronze vessels for generations to come. “I see a contribution of continuing my art to hopefully be an inspiration to the younger generation of my family or other tribal members,” Pahponee says. She balances the toggle between traditional ways of Woodland pottery and being a contemporary artist in the modern culture of the 21st century.

“I always think about what an amazing time [it is] to be alive right now, because as an artist, I can know both. If I know what the traditions of my people are, it’s up to me to practice those. And if I know

what the modern world around me is doing, it’s up to me to participate [in] whatever my guidance tells me to,” Pahponee says. “For me as an artist, having a big palette to play with is really interesting because it allows me more diversity.”

“We have always followed the buffalo. The buffalo gives everything to us—physically, mentally, spiritually.”

Her practice remains in the Woodland tradition by firing some of her pots in buffalo chips (dried buffalo dung). She is the only living member of her tribe to still practice this technique.

“We have always followed the buffalo. The buffalo gives everything to us—physically, mentally, spiritually. They have given their entire body so people can survive. So we never waste anything. I still fire my traditional pottery using the dry buffalo chips because that’s the way the old women used to do it,” Pahponee says. “One of the ways that buffalo still provides for me today is through my art. If I couldn’t gather those buffalo chips and fire that way, we wouldn’t be having a conversation about traditional Woodland pottery because it wouldn’t be happening.”

Traditional Woodland pottery has been carbon dated back to what some experts believe to be 7000 years ago. Pahponee believes the traditional Woodland pottery is rooted in its materiality, in the rocks

and geography of the land it was original to. This material from the Great Lakes region makes Woodland pottery unique, and those Native artists working amongst the region’s influences create pieces with an essence of that way of life.

“The geography under your feet, the earth, the soils, all of the raw materials that form our pathway that we walk on—they have their own tailor-made reason for being where they are. If you’re using the materials from that region, they have a unique color, a unique texture; they have a unique way they like to interact with the fire.”

The potter’s role, then, is to learn those -isms of each clay, regardless of the region of origin, because every one will be unique.

“If you’re using the materials from that region, they have a unique color, a unique texture; they have a unique way they like to interact with the fire.”

The lost wax method of casting uses the original clay pot as a prototype to make a wax mold of it. The wax mold is then dunked and coated many times in a slurry until it looks like an imploded, swollen version of the original shape. The wax is then melted out from the inside, leaving the impression of the desired vessel in its wake. The cavern is then filled with molten bronze that settles in the exact form of the original clay. Once settled, the hardened slurry cast is broken away to reveal the bronze replica.

“It’s meticulous,” Pahponee says. But “to be able to replicate an original pottery form, now in copper instead of clay—and it has the same shape and thickness, the designs look good, the spirit is intact with it—I feel it’s alive with me.”

It is then at the art markets around the Southwest, like the Natural History Museum of Utah’s Indigenous Art Market, where Pahponee has a platform for her art to be sold amongst other Native artists from across the country.

“These art markets are so crucial. It allows living, working, Native artists to come out in public and present themselves [and] their art; [to] educate, visit with, sell their work, so that they can make a living and then go back to the studio to create more,” Pahponee says. “These art shows support the tribal way of life because then the artist comes back home and that money goes to a lot of places supporting the tribal way of life. It helps the artist have purpose, to know that what they’re thinking and feeling can be put into form and their art is going into a home that will be loved for the rest of their days.”

“It really was not that long ago that Native people were not welcome to go to museums, to give an artist talk, to have a solo exhibit.”

These markets are a stark contrast to the United States’ deplorable history of institutional assimilation and systemic erasure of Native American culture across the country. It’s especially significant in Utah, a state where the largest massacre of Native people by the US government occurred, the Bear River Massacre.

“I feel really lucky to be able to go to these markets because my great grandmother’s generation wasn’t asked to do those things. She wasn’t invited or accepted to go to the Smithsonian and present her art, and so that’s a great honor that I am in the time where I am asked to come and present.”

She believes that these markets acquaint the local community with Indigenous people and lifestyles indelible to the history of each place across this nation.

“It really was not that long ago that Native people were not welcome to go to museums, to give an artist talk, to have a solo exhibit. They were not invited nor were they welcome,” Pahponee says. “So we’re very fortunate that our people can stand up in a variety of ways, stand up in the legal system, stand up for our way of life, stand up and have our voice heard.”

See Pahponee and her work at NHMU’s 11th Annual Indigenous Art Market from October 12–13.

Read more artist interviews here:

Russel Albert Daniels’ “Wild Roses” Brings Visibility To Indigenous Communities

The Art of Being Monstrous with Lewis Figun Westbrook