Learning to Mind the Signs: The Renaissance of Salt Lake City’s Regent Street

Art

Salt Lake City has been called, with good reason, the “Crossroads of the West.” A new Downtown project, Regent Street demonstrates how SLC continues this phenomenon into the present day. It is the result of a collaborative effort, and as local conceptual design consultant Stephen Goldsmith puts it, Regent Street serves as a “case study of how excellent designers respond to a challenge.”

To understand the nature of this challenge and the process behind undertaking it, I spoke with Jesse Allen of GSBS Architects and Mark Morris of VODA Landscape + Planning. The two focused on the highly site-specific nature of the Regent Street project. Their concern was to create a functional public space that bore witness to Salt Lake’s history as a vibrant and diversified community. Allen and Morris feel that it is important to acknowledge that the overall project was ultimately managed by Justin Belliveau, Chief Operating Officer of Salt Lake City. Nevertheless, they insist there was never any grand mastermind dictating the details or their final arrangement. These were worked out progressively by an 18-member committee. “This was always a multi-disciplinary collaboration,” Morris says, “one which we shared with a team of experts from a variety of firms and professions, as well as input we solicited from the larger community.”

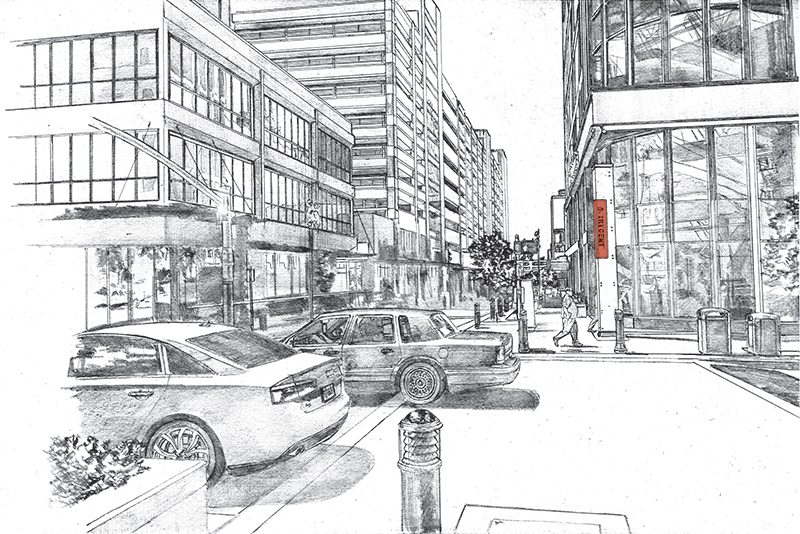

Regent Street, prior to its recent redevelopment, had lain neglected for decades, a virtual dead space running parallel to Plum Alley. The opening last October of the new George S. and Dolores Doré Eccles Theater at 131 Main St. created a number of opportunities with respect to the adjacent area; in particular, the passage behind it, 40 East. Morris explained that the team wanted to convert an unused “mid-block street into a functioning and lively public way,” he says. This space would need to accommodate pedestrian and vehicular movement. Such traffic would consist of coming-and-going theater patrons, performers and theater staff, and semi trucks and emergency vehicles needing ready access to buildings and utilities. Further, the space was conceived not simply as a conduit linking centers of arts and culture but also as a site of sustained attention. Regent Street should be an attraction unto itself.

These requirements needed to adhere to the safety and efficiency standards managed by a variety of utilities companies and civil engineers. Over the years, Regent Street languished behind a multi-story parking facility. “It was essentially an urban junk room,” Morris says. “Beneath the pavement was a tangle of hidden basements and utilities. The city employee directing the excavation—he’d had his job for years—said this was the most difficult project he’d ever seen.” The complexity of the situation arose from the rich history of the street, which had, from its beginnings, served as a highly marked multicultural and multi-use space.

“Regent Street’s oldest feature,” Allen says, “is the old Felt Electrical Building.” For years, this had stood next to an abandoned and weed-entrapped fast-food restaurant, one known for changing hands over several months and notorious as a key example of Salt Lake urban blight. Currently, that lot has been emptied to make room for a new hotel. The new construction, however, had to be planned and built so that it did not detract from the character of the Felt building, which has been standing since 1871. “The Felt Building originally housed a cigar factory on the ground floor and a brothel above,” Allen says. Regent Street had served as a part of Salt Lake’s Chinatown until the 1950s, westwardly parallel to Chinatown’s center, Plum Alley. In 1913, the corner of Orpheum Avenue and Regent Street became the only place in which socialists could speak in public. Regent Street had also been the bustling center of Salt Lake newspaper and printing businesses.

Goldsmith encapsulates the aim of Regent Street: to “make the unseen seen.” But the large set of variables made the project uniquely challenging. So did the prospect of balancing the agendas of various agencies, such as the city’s Planning Offices, Parks Division and Department of Public Safety. One small but important index of this massive coordination effort is the presence on Regent Street of “Yield To Pedestrians” signs. “These are the only signs of their kind in the city,” Allen says. A crucial part of fully experiencing Regent Street is learning to recognize and read its various signs, even the most incidental, as traces of the host of conflicts and compromises that hover behind each of them. For instance, Regent Street’s various street utilities—manhole covers, tree gratings, sidewalk and street gradings—are embossed with patterns and messages alluding to the different cultures and communities who have intersected there. Along these lines, the planters lining the street were painted red to recall both the district’s former Chinatown and the street’s history as Salt Lake’s demimonde. As Allen and Morris walk me along the length of the project, they point out that these same frequently overlooked fixtures quietly testify to a combination of practical and aesthetic considerations that went into their design. Each fixture represents an instance of successful negotiation and strategic compromises on part of the developers.

Then there are the more overt new features of the project. Among these are the street-lighting fixtures, which are painted black and fashioned to resemble those used in stage design with the Eccles Theater. “The light they cast can even be adjusted to match the color schemes of shows taking place within the theater walls,” Allen says. The overall effect is that of theatre as a permeable membrane, one allowing the building’s interior to spill out into the surrounding walkways. This is matched by the constant and visible coming and going of performers and theater staff. Whereas the design of other local theaters has tended to segregate performers and audiences, Regent Street facilitates the intersection of their paths, the points of convergence functioning as a kind of stage on which public action and civic interaction can arise.

Other features contributing to this end will be a row of restaurants, immediately across the street from the theater and onto which its exits will open. These restaurants have not yet begun to set up shop. “We can’t reveal any specific names at this point,” Allen says, “but leases are currently being signed, and these business will be predominantly local.” Morris also foresees this area eventually hosting a row of small, tavern-like shops. At present, the area includes a number of wall and pavement plaques that cite literary figures such as Wallace Stegner and Mark Twain and offer commentary on the history of Salt Lake. Also lining the walk are rows of multi-purpose wrought-iron hanging poles that can be used to mark the site with suspended lights, banners or canopies according to occasional needs.

In keeping with a Regent Street created not simply to walk or drive but also at which to read, the design team enlisted the Struck creative agency as a branding consultant. Agency representative Kevin Perry informs that Struck’s role in the project focused on site-making, which “involves using artifacts to connect people to places in ways which foster continual growth,” he says. For Perry, relations between persons and places are not merely utilitarian but also emotional. The arrangement of retail images and copy, public art, historical markers and other signs should be integrated so as to foster a meaningful symbolic and narrative environment. “Branding should set a tone,” he says, “and encourages future designers to develop this space in a way which follows the precedent set by the current project.”

Finally, all these many considerations and decisions should remain open to the unforeseen ways public use contributes to the look, feel and direction of a given environment. As Goldsmith says, “I favor responsive, intimate and organically emerging plans that connect to create the whole and invite many voices in their creation.” If a design team can cooperate to assemble the infrastructure necessary to facilitate such dialogue, it should be possible to nurture a public sphere that is spontaneous, diverse and democratic. Goldsmith again captures this hope in a phrase, one taken from Jane Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities: “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

Editor’s note: Due to some historical misinterpretation, we added the information about socialists in the fifth paragraph and removed a misquote regarding Salt Lake City’s Chinatown on Regent Street.