The Brewing of John Bolton & Salt Lake Roasting Company

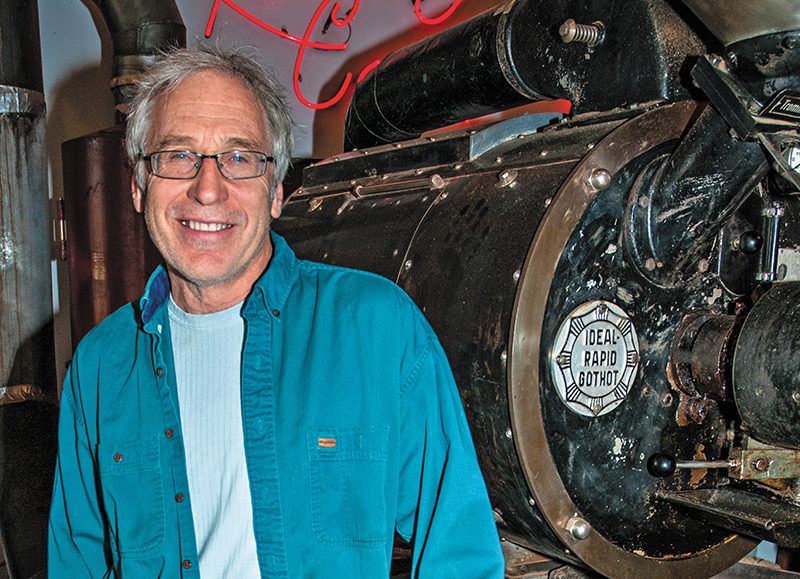

Art

I was greeted at Salt Lake Roasting Company by owner John Bolton and a wave of freshly brewed coffee, the sounds of grinding beans and conversations in foreign languages. An older gentleman was buried in the newspaper, a family was catching up and a teen was typing away. SLRC is not reserved for only the hippest or trendiest coffee drinkers in town, but serves as a “melting [s]pot” for all the coffee-potheads in town.

Bolton began as a dishwasher at the Rustler Lodge, then eventually transitioned into a chef. For seven years, Bolton was a chef at Snowbird but was “frustrated with the quality of coffee.” “When I went to San Francisco and New York, I had good coffee,” he says. “I knew it existed, but it didn’t exist in Utah. So I bought a small roaster while I was still chef-ing and roasted coffee from 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. after I finished work.” In 1982, his first two accounts were La Caille and, yes, Snowbird.

Bolton started roasting in a Sandy warehouse in October 1983, and then opened Salt Lake Roasting Company’s first retail shop in the building where Stoneground is now. Bolton’s passion for roasting coffee began in an age when it was a rebellious act to drink coffee in Salt Lake City, which actually helped his business. “I had an enviable monopoly—I had no competition in quality coffee. The business grew rapidly and well, and I’m very grateful for that.”

Young and single in 1985, Bolton capitalized on the industry to travel to regions he knew had great coffee, “to learn about the culture behind coffee, embrace [those ideas] and buy direct.” Having now visited 28 countries of origin, he realizes that coffee is not a passion for the farmers but a way to exist, and he must ensure they are paid a fair wage. Travel is not required, but “gives you a good perspective, compassion and respect,” he says. He respects the Guatemalans for having “fewer outside influences,” he says. “They are at peace with who they are and not trying to impress anybody.” The Ethiopians are transparent, without a profitable agenda. Bolton respects the diversity in Indonesia, which has over 10,000 islands, multiple religions, more than 700 languages, and each person with their own importance in life: “I never felt a sense of comfort there, but it was fascinating,” says Bolton.

Bolton evokes the indigenous cultures in his coffee and verifies by “cupping” thousands of cups per year. An epicenter of his business, cupping is the practice of observing the tastes and aromas of brewed coffee. Bolton drinks black coffee, but realizes not everyone does. “When I first opened, I was kind of snooty,” Bolton says. “I thought flavors were for wusses—if you wanted coffee, you wanted coffee,” but he admits that “people should be able to have coffee the way they want, and my job is to give them the best product I can—and if they want to put vanilla syrup in it, let them.” He doesn’t flavor coffee beans in order to uphold the natural smell of coffee beans, which reinforces the coffee-shop feel and smell, though he permits the addition of flavors after brewing.

A well-crafted cup of coffee lends itself to be consumed black and allows you to fully taste and acknowledge the origin and the art of coffee roasting. Bolton is immersed in a craft that he hopes others can admire. “My approach is artistic,” he says. “Not that I’m an artist, but my approach is empirical: I see, smell, touch and taste to get the right thing.” While the product is important, so is the presentation. SLRC is currently working on a location move. Bolton credits his staff for harboring his artistic vision while also pushing him to make necessary changes to grow as an owner. With the move, Bolton hopes to ramp up his online presence and communicate that SLRC is moving and making positive changes.

The coffee industry challenges Bolton to stay relevant among a new generation of entrepreneurs and technology. “Everyone chooses to put a face to the public with a different emphasis,” he says. Bolton’s emphasis is “to educate, to go to source, to have a story—to talk about where the coffee came from, who grew it and what was important in their lives.” Bolton cares for his farmers and customers, too. “That’s who I am and what’s important to me, that whoever comes in here feels comfortable.”

Bolton believes that a shop must be “an extension of oneself,” but realizes it’s easier said than done: “I want to be relevant to a new generation, and yet I want there to be continuity in what I’ve done in the past,” he says. SLRC is downsizing, sacrificing space for quality. There will be more emphasis on coffee and grab-and-go food with a pour-over station where you can taste from 40 different coffee selections. Bolton mourns the end of the big-coffee-shop era but will do what he does best, “and that’s coffee,” he says. The new location will still have the warmth of the current location with maps highlighting indigenous cultures. “If people want to know about coffee, I’ll talk their ear off, but if they just a want a cup of coffee—that’s great. Put cream and sugar in it, feel at home,” says Bolton, “but you can appreciate it black, too.” Coffee, however you take it, is a cultural statement—as long as the coffee is pouring, a story is brewing.