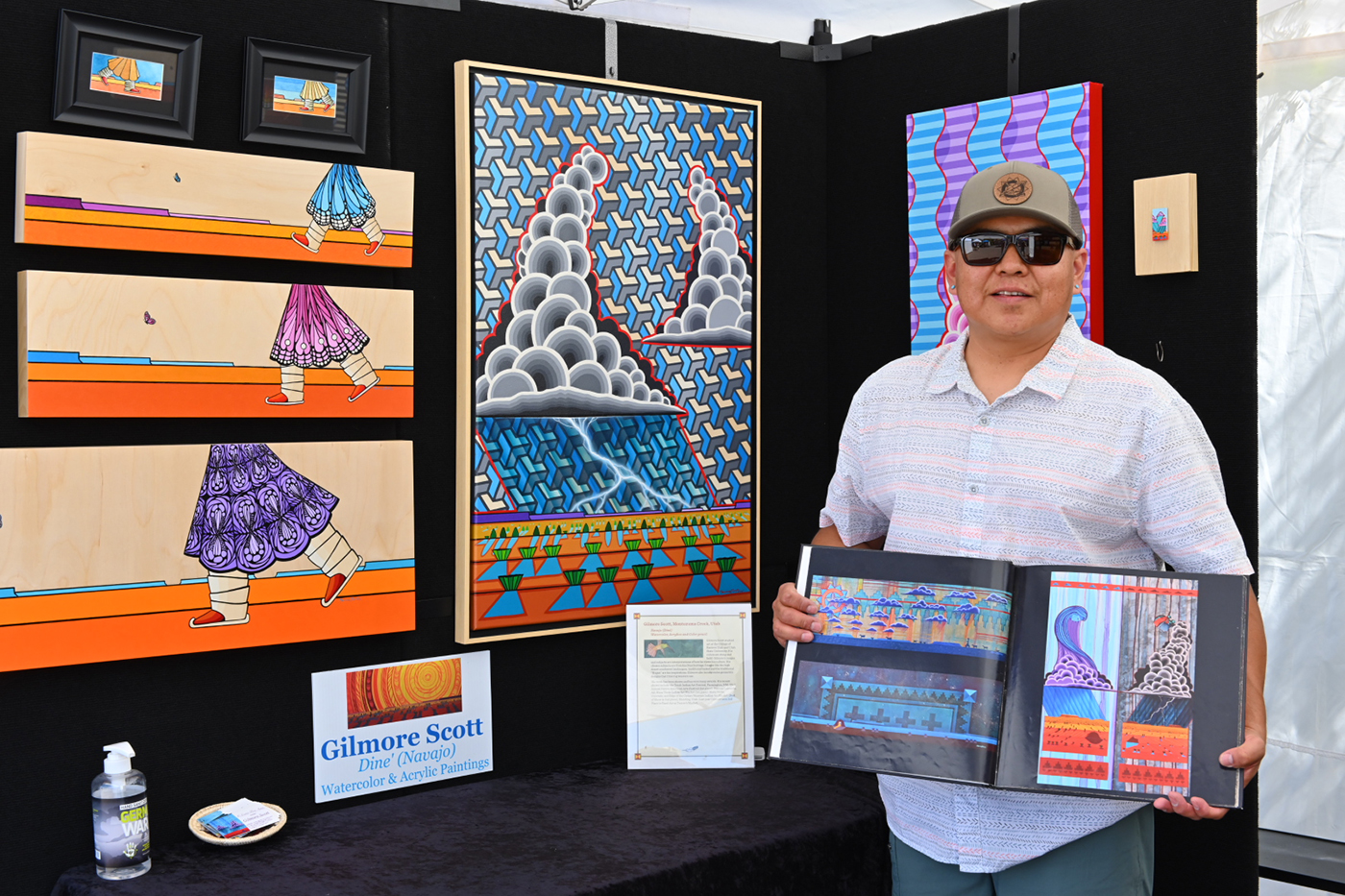

Gilmore Scott: The Landscape from the Artist’s Point of View

Art

Gilmore Scott has been creating art for as long as he can remember. From the Southeastern corner of Utah, Scott brings his original pieces to viewers digitally and through local art shows across much of the state. With vibrant, high-desert depictions, Scott hopes that viewers see the landscape from a richer and more complex point of view. “[Being an Indigenous artist], I want people to know that we’re still here … not just in storybooks or movies. Folks tend to think that our style of work is meant to be viewed at roadside art booths, but we’re being approached by museums and placed into them,” Scott says.

Scott’s identity as an artist and his Diné heritage are profoundly intertwined. When asked for his pronouns, Scott responds, “I am an artist and traditional Native American—if those can be considered my pronouns.” The artistic influence that surrounded him as a child was an undeniable catalyst in his art career. His mother is a rug weaver and silversmith, so Scott grew up watching her create traditional rug patterns. “I would watch her weave as a kid and then repeat those patterns in my drawings. Once I got older, I started to look toward my culture again,” Scott says. Many of the geometric patterns Scott produces are inspired by rug weavers’ sacred designs linked with the stories that are passed down from those particular nations. As the background of more than half of his work, these vividly angular patterns provide the silhouette for Scott’s art.

“I was always looking from the sky down on the landscape, and that’s played a big influence in my shadow work.”

While in college at Utah State University Eastern, Scott was encouraged by his counselor to study nothing but art. “I dove into photography, digital art, sculpture … anything I could get my hands on,” he says. As a mixed media artist, Scott paints with oils, acrylic, pencil and watercolor. He is known for painting certain subjects repeatedly while altering the colors in each original work. The electric reds, blues, purples and oranges are integral in the way he perceives the desert landscape. Scott’s paintings of slanted shadows are never simply sketched with a light hand but drawn with definitive, bold lines. In the painting “Monsoon Thunder Clouds, Sky Dazzler,” billowing, gray-black clouds release a burst of lightning onto a foreground of terracotta buttes. The unwavering shadows from green crops amid the storm suggest a connection from the sky, to earth, to people that can not be disentangled. The expansive point of view from which Scott paints was also inspired by his nine years with the U.S. Forest Service. Working with the repel crew monitoring fires, “I was always looking from the sky down on the landscape, and that’s played a big influence in my shadow work,” Scott says.

The Bears Ears National Monument is frequently depicted in Scott’s work. For example, in the piece “The Bears Ears Monarchs,” four women walk in their traditional skirts from east to west. “The footwear of the women represent the four Indigenous groups of people from this area: The Zuni, The Hopi, the Diné and the Southern Ute,” Scott says. He frames the women leaders in butterflies because, he notes, “a lot of Southwestern Indigenous people are matriarchal, and I’m playing on the word monarch and matriarch.”

“[Being an Indigenous artist], I want people to know that we’re still here … not just in storybooks or movies.”

Scott’s oeuvre reflects a deep and ever-present meditation on the Diné’s relationship to the Southwest desert. The viewer’s glimpse into the history and present lives of the Diné peoples is one outlined in incandescent colors and meaning. As a leader in the modern art movement from the Diné nation, Scott inspires viewers to reconsider what Indigenous art has meant to them and what it could mean moving forward.

To see Scott’s work in person, follow his Instagram at @gstruarts where he posts the shows in which he is featured. His website, with images of his work, is gscott-tru-arts.com.