Forget the Photography, Remember the Story: For Rick Egan, Photojournalism is About Changing Lives

Art

If you follow local news, it’s likely you’ve seen one of Rick Egan’s photos. Egan, a staff photographer for The Salt Lake Tribune since 1984, has spent the majority of his life documenting Salt Lake City in photographs. Photojournalism as a practice, though, is quite different from other types of photography. “[In] photojournalism, we don’t really set things up,” Egan says. “We don’t tell people what to do or what to wear or how to act or anything. We kind of just shoot what’s there. And so, we have to be prepared for anything.”

Egan has had a camera in his hand since he was a child. When he went on a mission for the LDS church to Ireland, though, he was introduced to the punk scene, and the rest is history. Irish people who were into punk rock were some of the only people who would talk to them as missionaries, and he got to know the community and the music well.

“We kind of just shoot what’s there. And so, we have to be prepared for anything.”

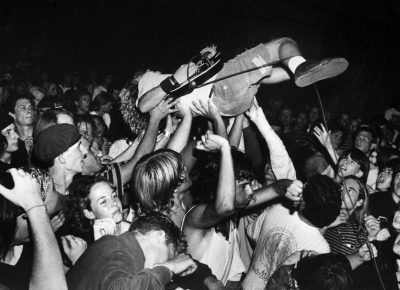

When he got home, Egan got into punk and hardcore even more, and he started taking his camera to shows in the ’80s. The scene wasn’t something the Tribune ever really covered, so Egan documented it on his own simply because of his love for it. “It wasn’t really like I wanted to document the scene,” Egan says. “I was just fascinated [with] the music, and it was so cool to see these young kids playing such neat stuff, and the power and the energy was incredible. And I was like, ‘I gotta capture this somehow.’” He went to every show he could and has photographed everyone from local bands such as Massacre Guys, The Boards and The Stench to more well-known bands like D.O.A, Fugazi, Ignition and Black Flag.

Eventually, Egan became a well-known figure within the scene. In his mid-20s at the time, he became the self-described “friendly neighborhood older dude.” Sometimes he would even do promotional work for bands—taking photos that would go on album covers, 7” records or flyers. Not in it for the money, all Egan asked for in return was maybe a 7” or a T-shirt. He’s still friends with a lot of the people from the scene to this day.

Through his photography, Egan was able to witness the evolution of the local punk and hardcore scene firsthand. From the beginning, he says there was an incredible sense of camaraderie. It was also definitely hardcore but never life-threateningly dangerous. “I drove more than one person to the hospital to get stitched up after they got ripped by someone’s Levi rivet that was stage diving or their nose broken by someone’s boot. But it was all good fun,” he says.

Photographing the punk and hardcore scene is far from the only work Egan has done, though. As a photojournalist for the Tribune, he has documented everything you can possibly think of, such as local festivals, events, protests, unsheltered communities and more. It was his college advisor that first told Egan he should be a professional photojournalist, but Egan wasn’t quite convinced until he went to a workshop with Anthony Suau, a photojournalist who documented the famine in Ethiopia. It was there he realized photojournalism isn’t really about photography at all.

“It’s about telling stories. It’s about making a difference in people’s lives … and bringing these stories to people that wouldn’t necessarily see them.”

“It’s about changing lives,” Egan says. “It’s about telling stories. It’s about making a difference in people’s lives … and bringing these stories to people that wouldn’t necessarily see them. … These photographers that showed these pictures, they weren’t talking about photography.”

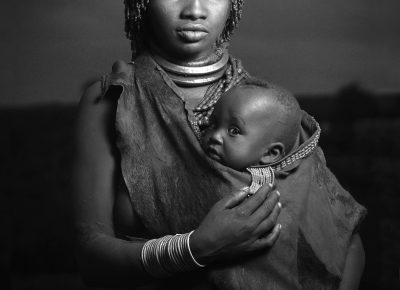

Egan has had his own experiences in Ethiopia as well. Friends of his were adopting a child from Shashemane, Ethiopia, which has become a place of pilgrimage for people of the Rastafarian religion. Having also been introduced to reggae while living in Ireland, Egan decided he had to go. While there, he became connected to the Children of Ethiopia Education Fund, which helps raise money so young girls there can have a quality education. The experience was life-changing for Egan. “It was just this thing that just hit me so strongly,” Egan says. “I can change some person’s life with just $20 to $30 bucks. I don’t need to adopt someone; I don’t need to have thousands of dollars; I can change one person’s life with just this little bit of money.”

Becoming a sponsor wasn’t the only way Egan found a way to help out. He put his skills to work and took photos and videos of the children in the schools for the organization as well. He has made the trip again and again over the years, using his personal vacation time to do so. “I never thought photography would lead me to places like this,” Egan says. “That’s kind of … I guess one of the beauties of photography and art is being able to change lives.”

More recently, Egan has spent a lot of time photographing Black Lives Matter protests and local unsheltered communities for the Tribune. As a photojournalist, Egan has covered many protests, but the energy of the BLM movement this past year was unlike anything he had seen before. No matter how many people showed up, he often saw the same people out there every, single day. While he himself must stay neutral as a journalist, he says he hopes the stories they tell will create change.

“That’s kind of … I guess one of the beauties of photography and art is being able to change lives.”

A lot of the protesters were the same people Egan saw volunteering to help unsheltered communities as well. “It’s really been a cool year for me as a photographer to get to see that kind of passion, you know, down-to-earth people down there working with people that need help just making it work on their own without having to go through some agency to do this,” Egan says. “They just go over there and take them food. ‘What do you need, water? We’ll bring you water.’ It’s kind of a punk-rock way of helping people.”

Now disbanded, Egan spent a lot of time at Camp Last Hope and says photographing these communities is not only important for historical documentation but also for these people’s stories. Because of the Tribune’s wide reach, he hopes their stories can inspire people who want to help but may not know how to, whether it’s washing blankets, bringing firewood or more.

Egan himself has spent some time on the other side of the lens recently. He was pepper-sprayed in the eyes by a Trump supporter at the state capitol on Jan. 6 while the insurrection was happening on the other side of the country. The thing was, Egan says, he didn’t even know what was happening in Washington, D.C. until he got to the state capitol. He even says things were pretty “sleepy,” which made him even more shocked when he was sprayed.

“It’s really been a cool year for me as a photographer to get to see that kind of passion, you know, down-to-earth people down there working with people that need help just making it work on their own.”

While the experience was bizarre, Egan says it wasn’t necessarily an attack on him because it could have happened to any journalist. “These are all those guys who hate the media,” Egan says. “We’re the ‘enemy of the people.’ They don’t want us here.” Egan wasn’t even the only person attacked that day. Carl Moore, a chairperson of PANDOS, had their phone stolen while live streaming the rally.

In the time since, there has been an outpouring of support for not only Egan but for local journalism as well. “It wasn’t me, it wasn’t a person getting sprayed, but it’s a journalist out trying to tell the story [that] was attacked,” Egan says. “And that’s the thing that’s important, [that] it doesn’t matter that it was me because … it could have happened to any of us.” The Tribune saw an increase in donations, and Egan says people were even offering to come protect them and give protective gear so they could keep doing their jobs safely. “I just am so proud to be working at the Tribune and proud to be at a place that cares about us, that cares about getting us the protection we need and sending us back out,” Egan says.

No matter what he’s photographing, Egan deeply cares about every person whose story he’s telling, which requires building trust with the community. He hopes that every photo he takes and every story he tells will inspire people and make change. “I mean, ‘the picture’s worth a thousand words’ is a big cliche, but I think … if we care about our subjects and care about what we’re shooting, we’ll take better pictures, and those pictures will be able to move people to action,” Egan says. “And that’s what I think is the beauty of journalism from all levels.”