Capturing Conservation and Colonization: Douglas Tolman

Art

From downhill longboarding steep mountain roads to sojourning along the colorful shore of the Great Salt Lake, photographer Douglas Tolman experienced an artistic journey that brought out a unique and crisp voice. Using props and the environment, his photography calls attention to the conflict between industry and ecology in the Beehive State. Describing his style as “place-centric, encyclopedic visual language,” his art is accessible, minimalist and grounded, inviting audiences to explore the landscapes of Utah from a fresh perspective.

Tolman started taking photos in high school by capturing thrilling moments while adventuring in the outdoors, especially downhill longboarding. “I really got to witness and photograph some magical moments bombing hills with friends in beautiful morning light,” he says. “Most importantly, I learned how to branch out from my religious, suburban community into an international community of people traveling the world in search of gnarly roads.” Soon, his photography gave him exposure, and paid opportunities allowed him to continue doing what he enjoyed.

Over time, however, Tolman felt that the capitalist pressures influencing his artistic vision weren’t worth the money. Instead, his attention shifted to industrialization’s threat of jeopardizing public lands. Today, his photography explores and documents Utah’s wild spaces and how they have been colonized. When asked if he had any suggestions for new photographers in Utah, Tolman says, “Don’t go to a destination to take photographs. Go places you want to be, and take photographs along the way. The world can do without another photo of Delicate Arch, but many of the pit-stops you’ll make down less-traveled dirt roads harbor lifetimes of meaningful stories for you to tell with your lens.”

“I intend to acknowledge and critique previous artwork made in the Great Basin by combining their concepts with the ecological and social issues they ignored.”

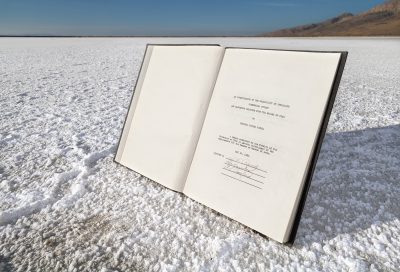

Throughout his career, Tolman has cultivated a striking, no-fuss style that serves to capture the raw nature of his subjects, whether it was a longboarder bailing out on a mountain road or a melancholy salt pile standing on a gritty shoreline. His more recent body of work focuses this approach on props and landscapes. “Some of my work involves displacing man-made objects (books, computers, etc.) into landscapes,” Tolman says. “On the flip side, some work takes piles of sediment into the studio as a representation of the land it came from.” Even when shooting landscapes, he likes to focus on prominent objects—such as smokestacks, salt piles and buildings—and uses them as props to contrast with the environment.

Previous artists—especially Robert Smithson, famous for his creation and surreal photos of the Spiral Jetty—greatly inspired Tolman’s work. Tolman says, “I have a lot of respect for land-artists like Smithson who used this landscape as their canvas, but I also have qualms with the idea that they thought it was theirs to use in the first place. I intend to acknowledge and critique previous artwork made in the Great Basin by combining their concepts with the ecological and social issues they ignored.”

In that vein, Tolman’s art has a strong and consistent political voice. Growing up, his philosophy was shaped by stories about his European ancestors colonizing the Salt Lake Valley. As a descendant of settlers, his art reckons with the cascading impact that event had on the environment, the indigenous population already living here and the health of future generations. “My artistic angle is an attempt to open conversation about the health problems and ecological damage caused by industrial colonization from my point of view as a visitor to this land,” he says.

[Douglas] Tolman seeks to add perspective to the discussion, urging people—many of whom are also descendants of colonizers themselves—to recognize the impact of colonization in their backyard.

His photography presents a sober vision of the land and its scars—barbed-wire fences, multicolored saltwater pools and fuming power plants viewed from the perspective of someone exploring unseen facets of a familiar place, a visitor in their own home. The Great Salt Lake was a natural place to explore from this vantage point. “The lake started as a place to explore, hike and take photos,” he says. “The more time I spent out there, the more I noticed the surrounding industrial facilities I hadn’t heard about. A magnesium mine which was the nation’s worst air-polluter for decades, hazardous-waste incinerators, chemical- and biological-weapon-testing ranges, nuclear-waste storage—the list goes on. Many of these facilities are unknown to the 2 million residents downwind, even though our health is significantly affected by them.”

Tolman gradually peeled back a status quo taken for granted by many, then actively explored the dissonance underneath the surface. He doesn’t want to appropriate anyone else’s trauma, recognizing and supporting the profound importance of native and minority voices in the conversation about conservation, ecology and health in the American West. Rather, he seeks to add perspective to the discussion, urging people—many of whom are also descendants of colonizers themselves—to recognize the impact of colonization in their backyard and what responses it demands. So far, he says the community has responded very well to his work and philosophy.

Currently, Tolman’s work is on display indefinitely at Finch Lane Gallery as a part of the Artists of Utah’s 35×35 show. He also received several best-in-show awards at both the Senior Show and the Annual Student Show at the University of Utah with the help of mentors and collaborators. Tolman is currently working on a documentary following his 1,400-mile, self-supported bike trip where he examined the varied relationships between rural Utahns and the land. Once larger social gatherings are permitted again, he will announce pop-up screenings on his Instagram @douglastolman.