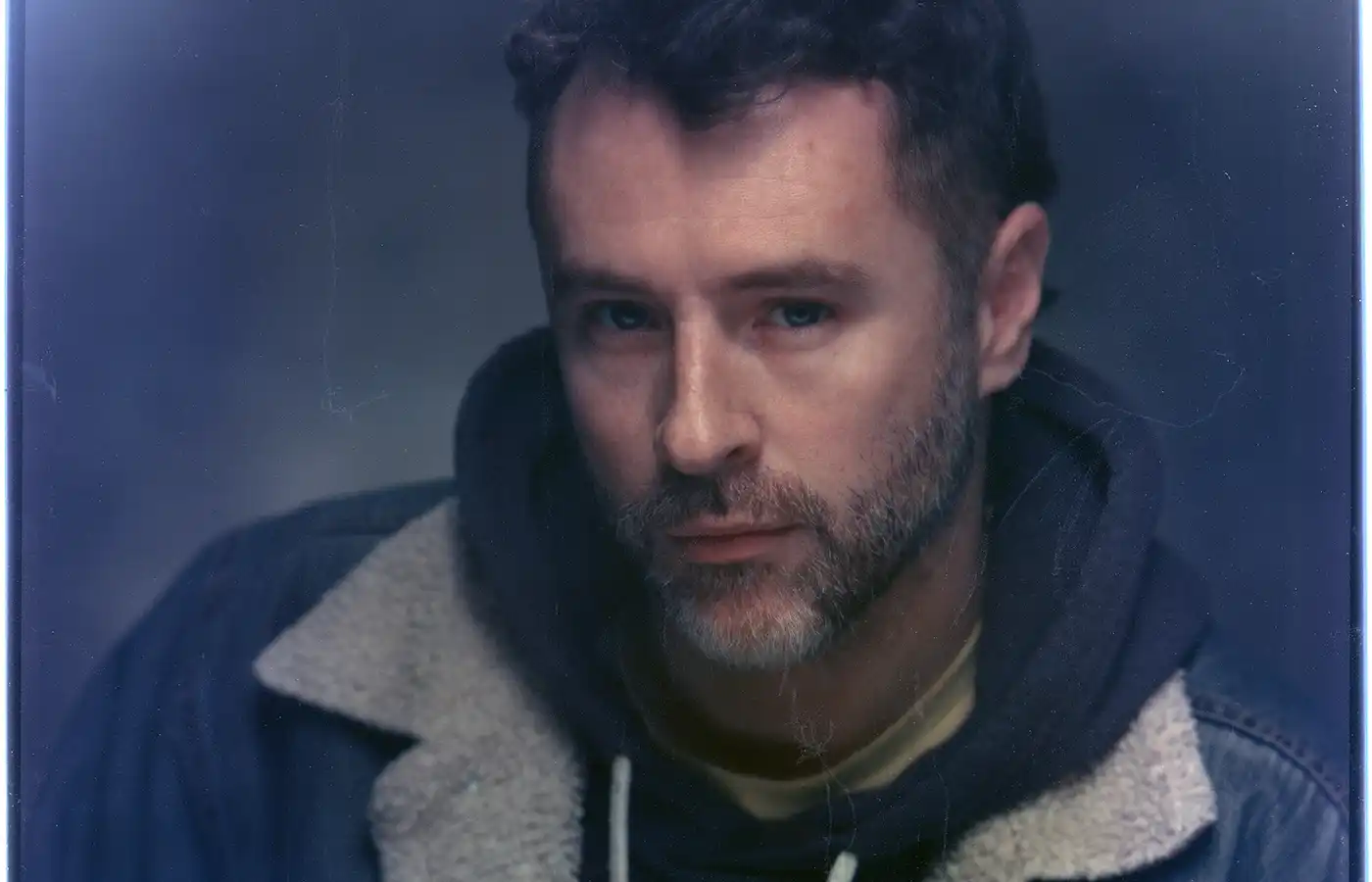

Brett Briggs: Capturing the Present with the Past

Art

Photo: Brett Briggs

In a high-paced, content-driven culture where anyone has access to take quick photos and upload them for everyone to see, photographer Brett Briggs is slowing down and redefining what it means to have your picture taken.

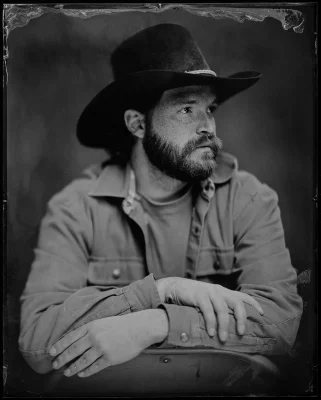

With over 20 years of photography experience, Briggs had been exposed to tintype photography several times in his life. It wasn’t until almost seven years ago when some of his favorite brands of film stopped production that he decided to make his own. Briggs focuses largely on portraiture and uses large-format (8×10), wet plate tintype, a medium invented in the 1850s. Wet plates carry a collodion—a nitrocellulose solution dissolved in ether and alcohol—that becomes light-sensitive when silver nitrate is added.

Tintypes pre-date film. The black surface of the metal that fits inside of a box in the camera makes a one-of-a-kind plate that can’t be reproduced, unlike a photo negative. This style of shooting can be arduous. The camera is huge, requires a ton of light and is really slow. “You have to make the film, which takes five to ten minutes. Then, you have to shoot it, which takes a minute or two. Then, you have to immediately develop it,” Briggs says.

“My process is kind of a paradox—how do you get people comfortable and natural while [they are] in an extremely intimidating and difficult environment?”

Photo: Brett Briggs

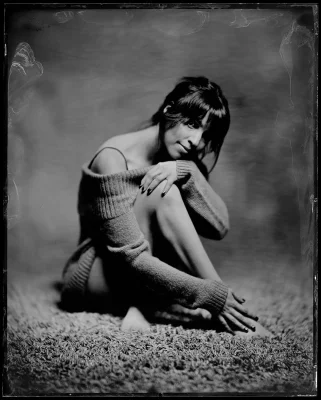

Briggs believes this process changes the dynamic of having your picture taken and compares it to sitting for a figure drawing class. “It kind of disarms people and unmasks them,” he says. With tintypes, people can’t go to their typical selfie angles and poses for those candid moments. Unlike traditional shoots where 100 images can be shot in 30 minutes and then combed through to pick the best ones, Briggs’ subjects have to come in knowing what they want and how they’re going to achieve it in only one or two shots. The tintype camera has a narrow plane of focus and takes a long time to shoot, forcing Briggs to be creative about posing his subjects. Moving even an eighth of an inch can completely change the image’s focus. “My process is kind of a paradox—how do you get people comfortable and natural while [they are] in an extremely intimidating and difficult environment?” Briggs says. He believes that being able to read people and get their input regarding poses and other visual elements helps to develop images that tell a story, represent someone’s identity, or portray a character.

The community of wet plate photographers is very small as this medium has a high barrier to entry and requires lots of skill working with dangerous chemicals. This is Briggs’ successful niche, where people or even pets can have their photo taken during one-hour, paid studio sessions and leave with a photo experience unlike anything shot with a phone or DSLR. His customers get to keep the final plate, a high-res digital scan, videos of Briggs behind the scenes setting up and directing the shoot and another video of him developing the tintype photos.

“You have to make the film, which takes five to ten minutes. Then, you have to shoot it, which takes a minute or two. Then, you have to immediately develop it.”

These sessions help fund Briggs’ own storytelling journeys, such as his yearly trips to national parks where he shoots portraits of the rangers. Looking ahead, Briggs would like to create a series of park ranger portraits that captures their classic, timeless uniforms and unique lifestyles while also making a larger statement of protecting public lands. Briggs also hopes to work on more high-profile portraits, make even larger prints (16×20) and try out shoots as a part of wilderness retreats.

Visit Briggs’ portfolio, bretterick.com, where you can subscribe to his mailing list to find out about upcoming wet plate workshops and other events. You can also give Briggs a follow on Instagram @bretterick for videos of his developing process.

Read more on local photographers using unconventional methods:

Jaclyn Wright’s Multi-Media Metaphor Leaves a Deep Mark

Levi Jackson Explores Illusions in the Promised Land