Pulitzers and You: Imagining a Better Future

Art

Driving to BYU Museum of Art’s Pulitzer Prize Photographs exhibition, I was skeptical. I love museums, but an exhibition on Pulitzer photography seemed like the kind of thing you might get just as much out of Googling from home. But what had me going was that the collection comes from The Newseum in D.C., which first opened when I was living there in 2008. That was the first year I actually learned to appreciate museums, and my trip to BYU completely reminded me how great it is to walk through a curated space. As opposed to being a chronological presentation or history of the prize, Pulitzer Prize Photographs is a quilt of our best, worst and most mundane moments. Walking through it imparts a sense of human mythology that simply seeing the awarded photographs each year just can’t.

The first photo you see is Robert Cohen’s “Protests in Ferguson.” It’s an amazing photo and one you’ve definitely seen: A young, black man is throwing a tear-gas can back at police. The photo is large, printed onto a semi-circular wall. It greets you as you enter and makes a strong opening argument for an exhibition on Pulitzer-winning photography—these are photos that make us hungry to learn more. This photo was of Edward Crawford during the 2014 Ferguson protests. He’s wearing an American-flag T-shirt, with a bag of chips in one hand while he winds up the other. His dreads sweep back over his head as he cocks his arm, obscuring his face but leaving his eyes clear. Crawford killed himself in May 2017.

What I noticed as I perused the exhibit is that Pulitzer photos tend immediately to trigger this desire for more context. They depict the world in ways that make us curious. While I think this is a generally good thing, I also think there’s an argument for a version of this exhibition that puts less priority on contextualization and external information and more priority on letting the viewer absorb the images just as they stand.

What first seems like an exhibition focused on capturing reality quickly becomes a show about absorbing images of societies, of learning about humans in a way that works best when presented both with and without context. These photos’ usefulness as a tool often requires context, but their intense specificity allows for us to do more emotional work, and taken together, we have a framework to attempt reconciling the evil and beauty in our world. A striking image and a striking story leave a lasting impression, one we can build on.

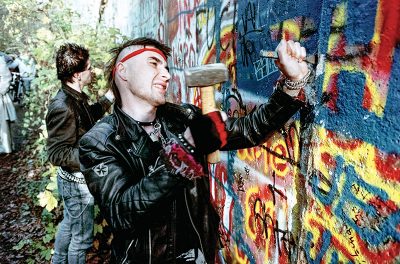

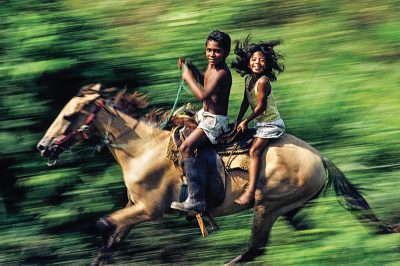

Instead of slavishly reading each placard next the photos, I started going through the exhibition, photo to photo. I tried not to make unwieldy assumptions, but of course, it’s impossible not to. “Boy Gunman and the Hostage” by Frank Cushing is an overhead shot of a boy standing in an alleyway, a gun pointed at his hostage, his head craned over his shoulder. In “Tragedy by the Sea” by Jack Gaunt Jr., we see a woman turning away from the ocean toward a man. She looks desperate and concerned. “Racial Attack on the Football Field” by Donald T. Ultang is a black-and-white football field; in the corner of the shot, away from the play, a white player needlessly bodies a black player. “Journey of Hope” by Don Bartletti captures two smiling children on horseback, an intense action shot with a green, blurred background.

Cushing writes about “Boy Gunman and the Hostage.” He’d arrived on the scene of a police shooting, and though they’d surrounded the gunman in an alleyway, Cushing convinced a neighbor to let him onto her balcony for the shot. Sometimes the details completely subvert your reading: “Journey of Hope” is a hopeful moment in a larger, harrowing context. Bartletti describes trying to document the migration of Central American children searching for parents who had immigrated to the United States. One day, as he’s riding stowaway on a train, two children burst through the bushes and rode for just moments next to his traincar. It’s a hopeful moment in a less-than-hopeful existence, Bartletti argues.

I got the most out of this exhibit by combining a surface-level, textual reading with one that’s more informed. A lot of exhibitions work well this way, but Pulitzer Prize Photographs especially. Photos of this consistent caliber and historical significance should encourage imaginative readings as much as descriptive ones—they become strongest in that synthesis.

To me, this was most evident in two photos, which sit next to each other in the gallery: “Kent State Shootings” by John Paul Filo and “Campus Protests” by Steve Starr. Taken in 1970 and ’69, respectively, “Kent” shows a girl screaming over a dead body, her peers only just noticing him and hearing her. In “Campus Protests,” black, male college students walk out of a building armed with rifles, bandoliers and shotguns in apparent preparation for a protest. I stared at these images in disbelief. “Kent State Shootings” should feel like a relic, but it’s all too familiar. “Campus Protests” feels unfamiliar—images of black people open-carrying—but shouldn’t. The context of both photos is important and helps us make better material decisions about how we can run society. But the image itself, that’s where we realize we’re even capable of choosing to imagine that better society.

You can see this curation for yourself at BYU Museum of Art. The exhibition runs until March 3, 2019, so you’ve got plenty of time. Visit moa.byu.edu for more information.