Don’t Go Down by the Water: The Drownings at Hobbs Reservoir

Local Events

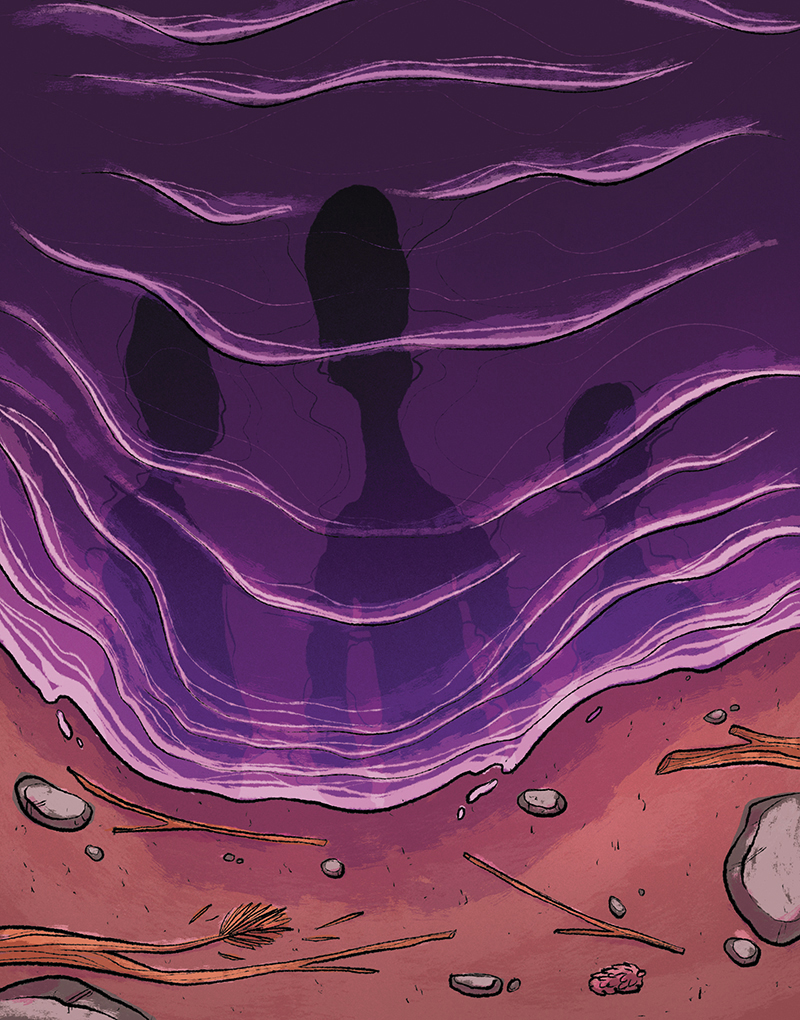

Most people don’t swim in Hobbs Reservoir often or for very long. At night, when the “No Swimming” signs are mute, the waters tell why. Reflecting the moon along the swell of Thurston Peak, some say they see, floating beneath, bodies hung down and still—or panicked faces trying to surface from the moonlit waters, calm then resigned, sinking out of sight. Over the distant hum of Layton and Hill Air Force Base, subdued moans and calls for help lie like fog around the water’s edge. If you could see far into the water, only 30 feet deep, you probably wouldn’t see the hands ready to pull you under, ready to roll your struggling body into the black loam like a wallet into a back pocket.

Ominously, a warning published in the Ogden Standard Examiner in 1943 from the Air Force urged soldiers not to approach the reservoir, calling it “polluted and unfit for swimming.” The first of the pond’s victims disappeared into the black waters on Aug. 6, 1944. A 19-year-old private, William C. Opey, and two other soldiers were swimming across the water at about 3 p.m. Opey cried out from behind the others—he was in trouble. Private William Smith swam back to Opey, ferried him some way across the length, but lost his strength with the sinking soldier’s weight, and letting go, Private Opey slipped under and down. He didn’t resurface. Now tired and mystified that his friend could slip out of sight of the world so easily, Smith continued on. The two remaining soldiers, now ashore, yelled and waited. Opey never surfaced.

Local authorities descended upon the reservoir with grappling hooks and drag lines in John boats. Some stood, plunging sticks into the loam. When this failed to bring up the lost body, searchers regrouped and planned. On Aug. 9, 1944, the Standard Examiner says, “Thirty sticks of dynamite” were used to blast the area of the reservoir, hoping to dislodge the body, but to no avail. However, the body was missing only a while longer, surfacing later that day. It must have come into view suddenly and with a dismaying casualness, as though the water, done with its prize, was returning it.

Oddly, even though he had died while breaking orders, Private Opey was later buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

July 26, 1959, seven kids were swimming in the reservoir. Two were floating on a log across the pond from where the other five played in the water at the bank. The two on the log called to Joe Junior Munoz to join them. The 16-year-old Salt Lake City resident set out across the still, sunlit water. The boys on the shore watched Munoz cross almost all the way, but about 15 feet from the boys on the log, he went under. Maybe a hand cleared the surface as his head went under and he flailed downward. The round wave of his torso dropping down disappeared, and the water stilled. The kids watched in horror for a moment and swam to his previous spot, finding it unoccupied, dark and without evidence of their friend, with no bubble nor waving arm.

This time, it took investigators, including police and highway patrolmen, an hour of dragging the water to find the lifeless, skyward-staring body and bring it back to land.

Two more 16-year-olds drowned in Hobbs Reservoir during the ’60s: Andrew Nightengale in July of 1965 and Michael D. Holden in 1968. Three years later, an 18-year-old man named Charles Humphrey was swimming with two of his friends when he went under. His horrified friends described him to authorities as a strong athlete.

By the summer of 2004, the privately owned reservoir was fenced off and the general area dotted with “No Swimming” signs. Police still were regularly issuing citations for trespassing to swimmers in these dangerous waters.

On July 29, 2004, an 11-year-old boy failed to return home after taking his dog for a walk near the reservoir. His mother, growing alarmed when he had been gone for hours, called police to help find the child. After 45 minutes of searching the area, an officer noticed, across the fence that blocks off Hobbs Reservoir, a dog sitting at the edge of the water. There, in the water near the dog … something. When the officer got to the dog, there were small shoes on the bank of the pond. And farther out, in the gray water, the child was submerged but visible. The awful event so overcame the officer who pulled the boy out that the Standard Examiner remarked on his sadness.

Recently, an internet reporter taking photos of the reservoir for The Dead History website—which hosts all the newspaper clippings referenced here—reported that while walking through the brush- and tree-lined trail, both her and her boyfriend’s camera phones, fully charged, would not turn on, drained of power. After some rough coaxing, Jenn’s partner’s phone came up, but was laggy and very slow to work. Jenn couldn’t get hers to turn on at all. When they got back to the car, Jen’s phone turned on, but battery life was at 50 percent, having been at full just minutes earlier.

The negative charge of the forbidden in the voices of the dead, crying out in the dark—the siren call of these drowning waters—continues to attract ghost hunters at night and legal fisherpeople during the day. But it is the daring and potentially lost soul that tries to swim across the reservoir who might find that, when they fail, they have really crossed to the other side.