Chaz Bojórquez on the Beauty of Cholo Tagging

Art

Ever since he was 15, Chaz Bojórquez knew he wanted to be an artist. But roaming the halls of Los Angeles museums for art classes as a kid, one thing, or lack of it, caught his attention: He found no Mexican-American artists or imagery that related to him.

“Racism and lack of personal identity made me see the world in a different way,” says Bojórquez. He saw beauty in the every day: lowriders, brightly colored Disney movies, advertisements and records attracted him, Bojórquez says. “I saw art in the public culture, not just in the galleries.”

Later, he says, wall graffiti of gang or crew names, street names and numbers—referred to as “placas,” which denote territory—became important to him. Immersed in this letter-based, Mexican-American culture that dated back to the 1940s, he knew he wanted to be part of it.

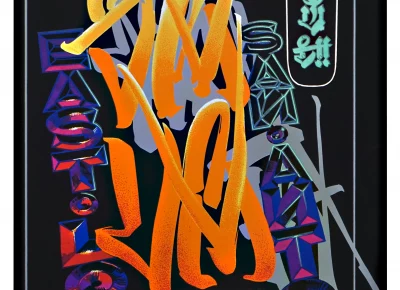

While Bojórquez says “it took another 30 years for the public to accept [graffiti] in the mid-1990s,” he has made strides in the tagging scene, credited for the distinctly iconic “West Coast Cholo” calligraphy. In his more than 50-year run, Bojórquez has collaborated with brands like Nike and Converse and exhibited his work at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

With an upcoming visit to Utah for Craft Lake City’s fourth annual LetterWest, SLUG interviewed Bojórquez about his start in the graffiti world, his biggest influences and what he sees in street art’s future.

SLUG: What was your first “Cholo” graffiti piece? How does Cholo graffiti differ from other graffiti styles, and why did you decide to go against the grain of what others were doing at the time?

Bojórquez: In 1968 ([at] 19 years old), I enrolled in Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles with a Ceramics major and a Painting minor. Again, I saw very few artists of color and everyone was creating typical contemporary American-style artwork—a European art history tradition. I was throwing clay pots, painting and drawing nudes during the day, and at night I would go out with my crazy hippy friends to tag the neighborhood.

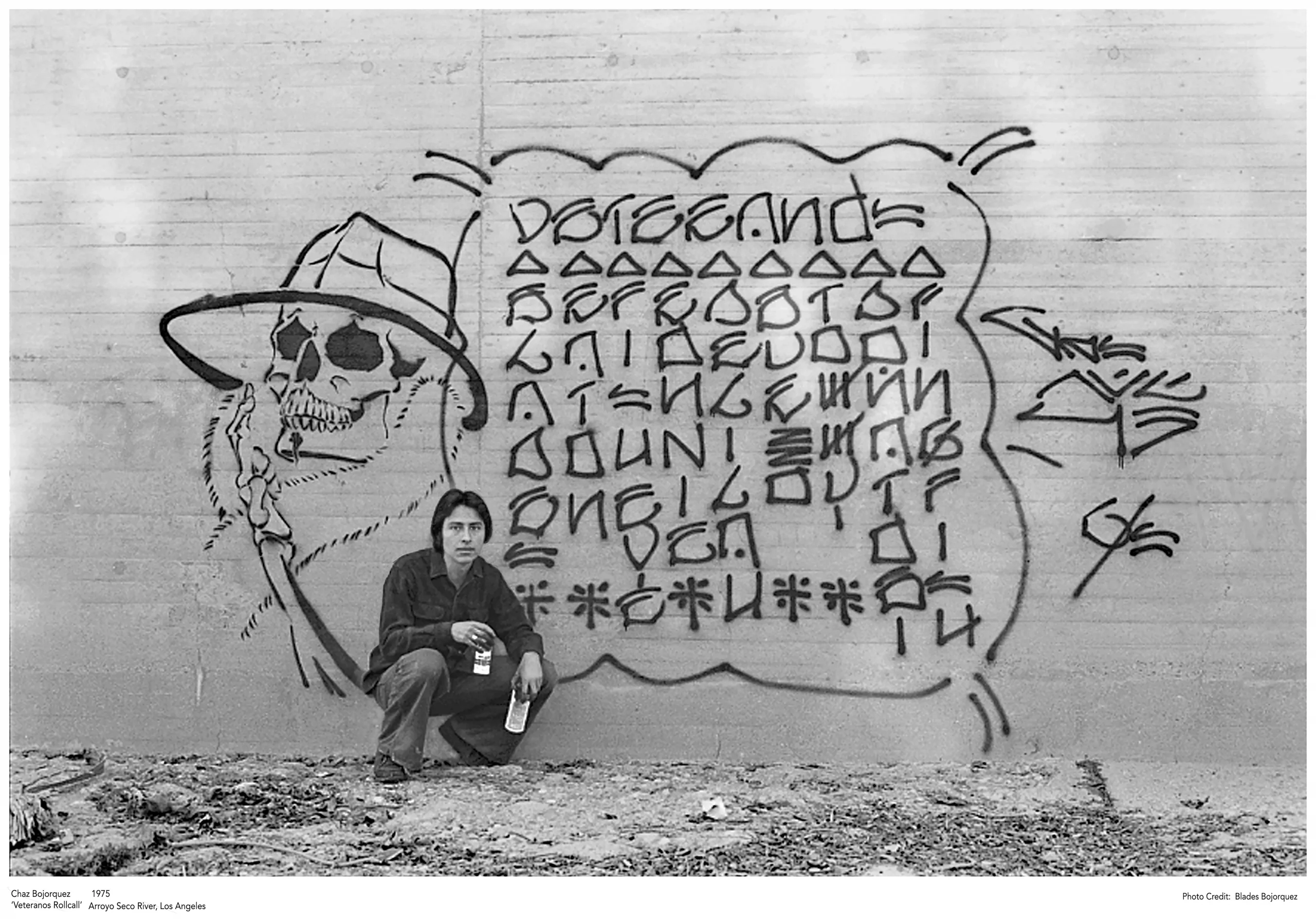

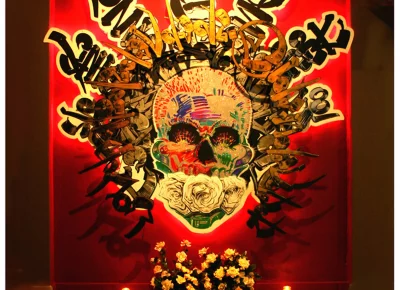

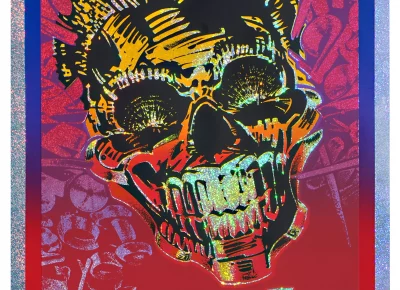

I felt different and wanted something new. First, I drew an image of a smiling skull—“Day of The Dead” style—then, added a New York fedora hat and fur-collared trench coats like in the movies Shaft and Superfly, and I crossed his fingers for “good luck.”

I had seen Mexican political party signage on street walls visiting my grandparents in Tijuana [that were] made with a stencil. That gave me the idea to use a stencil for my own tagging; faster and more tags per night was my thinking. Tagging my 5-foot-high skull stencil was so cool and used very modern materials for those times, a large sheet of Milar plastic.

I felt I was creating a new way to paint in the streets, years before Banksy (1990s) or Blek le Rat (1980s). My skull stencil was called Señor Suerte (Mr. Lucky). It was my way to be Mexican and American at the same time; it blew everyone’s mind in 1969. That skull stencil made my life’s career.

SLUG: What were the artistic influences behind the Cholo style?

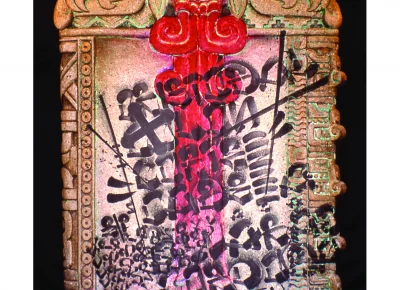

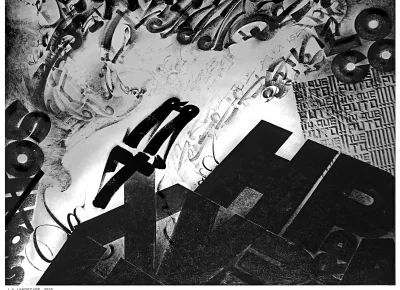

Bojórquez: Los Angeles has a unique style of graffiti tagging [from] the 1940s, before New York. The Latino culture used the most prestigious letter forms, and that was the “Old English” typeface. It has many names, but it’s the type from headlines of major newspapers, graduation, marriage and death certificates. We called it “Cholo style” because it was the name we gave to street gangsters. The graffiti lettering was always sprayed in black paint, all capital letters, side by side, like soldiers shoulder to shoulder. I was also influenced by Asian calligraphy; [I] didn’t know how to read it, but I liked it.

At 18 years old, I took some Asian calligraphy classes from a Chinese master who was taught by the brother of the last emperor of China. He said to [say] “take the line seriously” and “use your whole body when you use a brush, even when at a table.” Lessons I still use today.

SLUG: Are there any specific artists that deeply inspired your work?

Bojórquez: My direct inspiration came from the local gangs’ tagging and my personal interest in the Asian script and gesturing. There was no one using graffiti as an art form back in the 1970s—I was on my own.

The international graffiti movement that we see today came from the New York style in the mid-1980s. The New York subway cars were what turned on the switch for the world to start painting street graffiti. Los Angeles was the first to write, but we became a subculture in the art market.

My art training made me love the painters J. M. W. Turner for power, Johannes Vermeer for the moment and light, Chaïm Soutine for being hard and raw and Titian for being the first to find the face and soul of painting.

SLUG: How have you seen your street art influence local communities and artists?

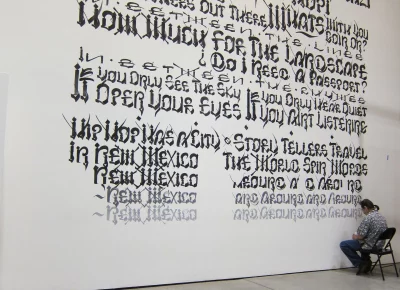

Bojórquez: Art has to function. Art needs a purpose. My work is about “letter-based” artwork. I found by studying the grammar of street writing that it had a structure: “Headline” the name of a gang or crew; “body copy” is a roll call of the names of the members or crew; the “logo” was the name of the person who wrote it or the name of your street.

My artwork style is a tool kit for me to use my letters as designs or logos and could be applied to products and clothing. It was easy to go from street lettering to corporate logo design. Some of my clients in the last 50 years [commissioned] titles for movies, books, tattoos, automobiles; designing street clothing, couture, shoes, jewelry, toys, prints, paintings and murals and much more were all done in the community and for the community.

I believe the most important artists are the ones who are the most influential in the art world. I started as a street tagger, but I now feel I am part of the larger world culture. Now I want

my artwork to “create culture.”

SLUG: What is one project that you constantly think back to, or a project that has influenced you the most?

Bojórquez: As a professional artist, I feel that the current job in front of me is always the most important, really.

But I can think back to when I was 14 years old and taking clay sculpture classes at a local museum. It was Marcel Duchamp’s first show in Los Angeles, and I was exposed to the original “Father of Conceptual Art,” way before Andy Warhol. One afternoon I came out of class, and I sat by the Koi fish pond and my teacher asked me if I wanted to meet Duchamp.

I asked [Duchamp] “How does one become an artist?” and he told me my first art lesson—”You don’t become an artist, you just do it!” Part of his exhibition was a prefabricated urinal and a bicycle wheel on top of a wooden stool. At 14, I told myself, “If he can make that art, I can make my own art.” Graffiti became my artwork, and I could prove it by painting it on canvas, and that took another 20 years to convince curators.

SLUG: Not only are you a big influence on the West Coast, but also across the country, particularly in Mexican-American communities. How do you see “Cholo” graffiti style as an outlet for identity, and do you think it’s done the same to other Chicano graffiti (and even non graffiti) artists?

Bojórquez: Being a graffiti artist is a “lifestyle.” It’s a style being used by many artists in many ways; it expands the definition of street art. One early influence of Cholo was painting on the side or back windows of cars with names like “Teen Angel,” “Tears on my Pillow” or “Sad Girl.” Tattoo inking was another huge part of using Cholo lettering—they are recognized throughout the world as L.A. style.

Magazines and car shows use Cholo for advertising; it’s a paying job for hundreds of artists. I receive emails from Brazil to Cambodia sending me photos of “Cholo Clubs.” They say, “We love the style about friendship and family, but we leave the violence out.” Crazy.

SLUG: You have an upcoming visit to Utah—how does the graffiti here differ from other places you’ve visited? Do you see a distinctive approach to graffiti in Salt Lake City compared to Los Angeles?

Bojórquez: Sorry, I don’t know Utah style and couldn’t compare it. Most of the cities in the U.S. paint the same N.Y. international style, but now it looks like psychedelic abstract letter forms. There is a coast-to-coast “Train Art” movement that I’m sure the towns of Utah are a big part of. I will be looking forward to my visit and seeing the Utah-style murals.

SLUG: How do you envision graffiti art evolving in the next few years?

Bojórquez: Are you serious? I haven’t a clue. There are “Rules of Graffiti.” Every writer knows them and they state “The rules of Graffiti are: There are no rules!”

I personally never thought I, myself, would be a major player in the Street Art international movement. In the beginning, it was for fun and I had only a dream to survive. There are no limits for the future.

SLUG: What inspires you to keep going in this particular medium? What do you think inspires other graffiti artists, especially those just getting into the medium?

Bojórquez: My inspiration has grown every year: exhibitions, jobs, meeting other artists, travel and adventure; I’m the luckiest artist ever. Graffiti is addictive; there is something about it that all artists say: “It grabs you and doesn’t let go!” We have the first generation of writers reaching 70 years of age and most still write, it’s still so much fun. I’ve been asked, “What have you done to help the young writers to stop them tagging?” I tell the writers to “tag more” because by tagging more, you become competitive. The more you write, the more you want your work to stand out and be better than other artists. It’s a macho game for young boys. Later, you want to do murals and design street clothing, publish a magazine or create merchandise, these actions get you out of the street and into the art market [to] make a living and become a contributing citizen. Once at that level, you don’t have time or interest to write illegal graffiti on the streets.

Graffiti has saved many of my friends’ lives, and [they’ve] also bought houses and cars for [their] families. I believe in this art form and the community has recently acknowledged my contribution to the art world by giving me an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Humane Letters by ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California.

Bojórquez, in his upcoming appearance at Craft Lake City’s LetterWest, will deliver a keynote speech and an exclusive workshop. To explore more with Bojórquez, purchase LetterWest event and workshop tickets when they go on sale November 25. To learn more about LetterWest, March 14-15, 2025 in Midvale City, and slated presenters, visit craftlakecity.com/letterwest.

Read more interviews with local and national artists:

Water and Rebirth in the West: Zak Podmore’s Life After Dead Pool

How the American West Shaped Dino Kužnik