J. Luke Heaton: The Triumphs, Troubles and Techniques of a Rural Luthier

Music

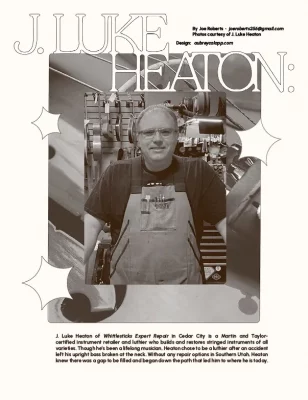

J. Luke Heaton of Whittlesticks Expert Repair in Cedar City is a Martin and Taylor-certified instrument retailer and luthier who builds and restores stringed instruments of all varieties. “Anything with strings, I work on,” he proudly claims during our interview, which takes place just before Heaton opens his shop for the day. On the wall behind him, a ‘30s Epiphone, a ‘50s Gretsch, a mandolin and violins in various states of rehabilitation hang from hooks, attesting to this craftsman’s skill and versatility.

Heaton was born and raised in Cedar City. In high school, he played upright bass in the Cedar High orchestra, intending to become a professional musician after graduation. During his senior year, however, an everyday accident put him on the luthier’s path instead. “I was loading my bass into the back of a truck,” he recounts, “and I just clipped the tailgate with the peg box. It broke off the whole top of the neck. I came to find out there was an older break there that wasn’t repaired very well.”

“I wanted a house, kids and dogs. And that’s really hard as a traveling musician. So I was asking myself, ‘What else can I do in the music world?”

Unfortunately for Heaton, there wasn’t a viable repair shop anywhere near Cedar City in those days. “We ended up having to go to Las Vegas to get it fixed. So a three-hour drive to drop it off and to go pick it up. And at this point, I’m like, ‘We need something here.’ I was still kind of planning on doing music performance, but this was brewing in the background, if you will. At the end of my senior year, I was just like, ‘I really don’t enjoy performing. I don’t want to do this for the rest of my life.’”

The desire for a family also factored into Heaton’s choice to become a tradesman instead of a performer. “I had scholarships for music performance for standup bass, but I wanted a house, kids and dogs. And that’s really hard as a traveling musician. So I was asking myself, ‘What else can I do in the music world?’” At this critical juncture, someone advised Heaton to attend violin-making school in Mount Pleasant under the instruction of Paul Hart, which he did. Then, after studying the luthier trade for four years, Heaton returned to Cedar City in the year 2000 and opened a violin workshop. As fate would have it, his new shop sat directly next to a failing guitar outlet.

When the guitar store went out of business, Heaton decided to get into guitar retail as well. He bought the store—along with its inventory—and moved his own operation into the space. At the time, he “didn’t even know how to tune a guitar,” though, so he began learning how to play and repair the newly acquired instruments. Fortunately, a lot of the woodworking skills he learned at violin-making school were easy to apply to guitar-making, so it wasn’t a steep learning curve.

Heaton now provides his community with what it lacked when he was a teenager: a reliable, local shop for crafting and repairing high-end instruments. In fact, Heaton just recently finished preparing all the orchestral instruments in Cedar City’s school system for the upcoming academic year. To top it all off, he has also built a fulfilling family life: his wife, kids and two dogs. He’s attained much that he aspired to in his early days.

Heaton’s favorite part of his trade is bringing beloved family instruments “back from death,” and he derives a great deal of joy from knowing people will treasure his instruments for the rest of their lives before maybe passing them on to their children. When I ask Heaton about some of his favorite projects he’s ever done, he shares a heartwarming story about a bluegrass musician from Arizona who hired him to restore her mentor’s old guitar—a 1950s Martin D-28.

“By the end, it was by far the best-sounding guitar I’ve ever played.”

“This was his bluegrass festival guitar. A real workhorse, and when she brought it to me, it was literally falling apart. She wanted me to make it totally playable again, but she wanted to keep the patina. So I took the dirt off and sealed the patina onto it. And I went through and had to replace part of the binding, had to glue back the top…” Here, Heaton rattles off a laundry list of intensive repairs that, to my untrained ear, sound indiscernible from building an entirely new instrument out of an old one’s bones. “By the end, it was by far the best-sounding guitar I’ve ever played. That is a cannon in a guitar shape. I don’t know what the mojo is. Maybe that guy’s soul is sitting inside the guitar making it work,” he laughs. “And now, she plays it every day. It’s her favorite worldly possession.”

Despite how fulfilling Heaton finds his work, though, being a small town luthier also comes with significant difficulties. Namely, running a business and making ends meet in an ever-shifting economic environment. “In the beginning years, I made most of my money on retail,” he tells me. “When I started doing this in 2000, no one wanted or dared to buy instruments online. And now, because of companies like Amazon and Sweetwater, I’m having to shift my business and make the bulk of my living in repair. Now we’re seeing companies like Sam Ash go out of business because COVID gave everybody two years to really get used to buying everything online.”

“The fun part of this job is that you’re never done, I’m always learning new things.”

“It’s harder to make a living now,” he continues, “especially in this particular moment when inflation has gone out of control. Bigger city luthiers have bigger clientele, so they can float a little better, but little guys like me really feel the crunch when the economy goes up and down.”

And while the times they are a-changin’, it isn’t all bad for the rural business owner. “The fun part of this job is that you’re never done,” he says. “I’m always learning new things.” He describes how he uses state-of-the-art technology to restore old instruments, making the process much faster and more affordable. For example, he tells me he’s going to use a laser cutter to make a replacement for a damaged inlay in the mandolin hanging behind him.

“With 3D printers, CNC machines and laser cutters, we’re expanding the toolkit we can use in this trade,” he tells me. “There are enough guys now that are into CAD and guitar stuff that we can start mixing the two together.” Heaton notes that this acceptance of modern technology marks a significant shift in the industry’s attitude.

“When I first started, everything had to be done by hand,” he tells me. “Especially in the violin world. If you weren’t doing this stuff by hand, you were just a hack. And now, especially within the last five years, there’s this big change of, ‘Oh, you can make this machine do something that we can’t even do.’ And it makes it more cost-effective for the customer.”

Heaton also spoke on the unique problems he faces as a luthier in Utah. “Because of our dry climate, I have to take things another step further than most guys would,” he says. Wooden instruments require high levels of humidity to stay healthy, so Utah’s arid climate is “the crucible for torturing instruments” in Heaton’s own words.

“I deal with so many cracks in instruments because there’s a lot of people moving to Utah right now, and they’re coming from much moister climates where they’ve never had to humidify their instruments. They don’t know they should. And they open their instrument’s case one day and find a big split running down the face because the top dried out.”

Heaton has come up with a brilliant solution to this problem. “I use a weaker hide glue,” he tells me, “so that if an instrument’s face gets a little bit of strain [from contraction], the edge will pop instead of the wood splitting.” According to Heaton, this method works so well because it’s much easier to reglue a popped edge than it is to fix a split in an instrument’s body. Additionally, the repairs needed with Heaton’s method are much less visible and impact an instrument’s tone far less than sealing up a crack in the wood itself.

In a world of impersonal retailers looking to make a quick buck selling factory-made instruments, Heaton’s attention to detail and willingness to think outside the box set him apart as an inspired and passionate craftsman. Heaton also likes to stay in touch with his clients, fostering meaningful artistic relationships and keeping tabs on the instruments he’s worked on.

Whittlesticks Expert Repair is located on Main Street in Cedar City or online at whittlesticksinc.com. Stop by if you’re in the area with a damaged instrument or if you’re looking to pick up a new violin, guitar or contrabass. Heaton also posts a lot of repair videos on Instagram, and watching him do his thing beats the shit out of doom scrolling, so I highly recommend following @whittlesticks.strings even if you aren’t in the market for a new fiddle or guitar-box.

Graphic Designer: Aubrey Calapp | aubreycalapp.com

Walk us through how you created this layout. What inspired you when designing it?

I wanted to figure out how I could marry the topic to my style. The article centers J. Luke Heaton, who works as a luthier but also fixes other instruments. I think fixing instruments is a pretty whimsical job, so I decided to add whimsical elements like sparkles and experimental title type along with a minimal color palette to match the simplicity Heaton presents his lifestyle with.

Tell us about your design background. How has your style evolved over time?

I got started by designing for independent zines! I mainly worked with music and arts topics, so I was able to focus on creativity early on in my design career. Since then, my style has evolved from a more maximalist eclectic look to a more organic and clean design style. I still love being experimental within certain boundaries though!

What are some of your design inspirations or influences?

I love looking to designers like Nicky Dolan and Baudoin Willemart and studios like Petrikór, Copy That, and As We Proceed. I also still love to collect and read independent zines—I highly recommend archive.qzap.org/index.php for some great ones.

What does your graphic design process usually look like?

I like to start by sketching/moodboarding, and then I try to follow that by getting all my bad ideas out immediately. I try not to expect my first or even second drafts to be good. I find that starting a project early and putting space between each round of revisions helps me a lot when it comes to finalizing a design.

What is your favorite aspect of graphic design?

I love typography. I have a lot to learn about it, but it’s such a cool way to display art and functionality at the same time.

Read more recent music interviews:

Contaminated Intelligence: Unbroken Brotherly Bonds

Lucinda Williams Is Too Cool To Be Forgotten