The Art of Being Monstrous with Lewis Figun Westbrook

Interviews & Features

For artist and storyteller Lewis Figun Westbrook, monsters aren’t something to run away from.

“Leaning into being this monstrous other… has been really satisfying because it allows me to let go of all these expectations on myself to take care of everyone’s emotions around me,” Westbrook says. “That’s just been so freeing, getting to be like ‘this is the me that you get.’ You don’t have to like it, but it’s going to keep being the me that you get.”

Examining what makes something—or someone—monstrous is what Westbrook (all pronouns/no genders) explores in their first ever solo art exhibition titled Monstrous: Being the Monstrous Other. The show, comprising 11 pieces spanning various mediums, “finds the fear behind ‘othering’ and does not hide from it.”

“I just have so many emotions all of the time; me getting to create art and getting to talk, bond and connect with my community are the two ways in which I can utilize the emotions I have to then reach more people,” Westbrook says. “I also find that, being neurodivergent, it’s very difficult for me to let my emotions stew and feel their feelings… so having art allows me to calm down and sit in that emotion in a way I wouldn’t naturally let myself.”

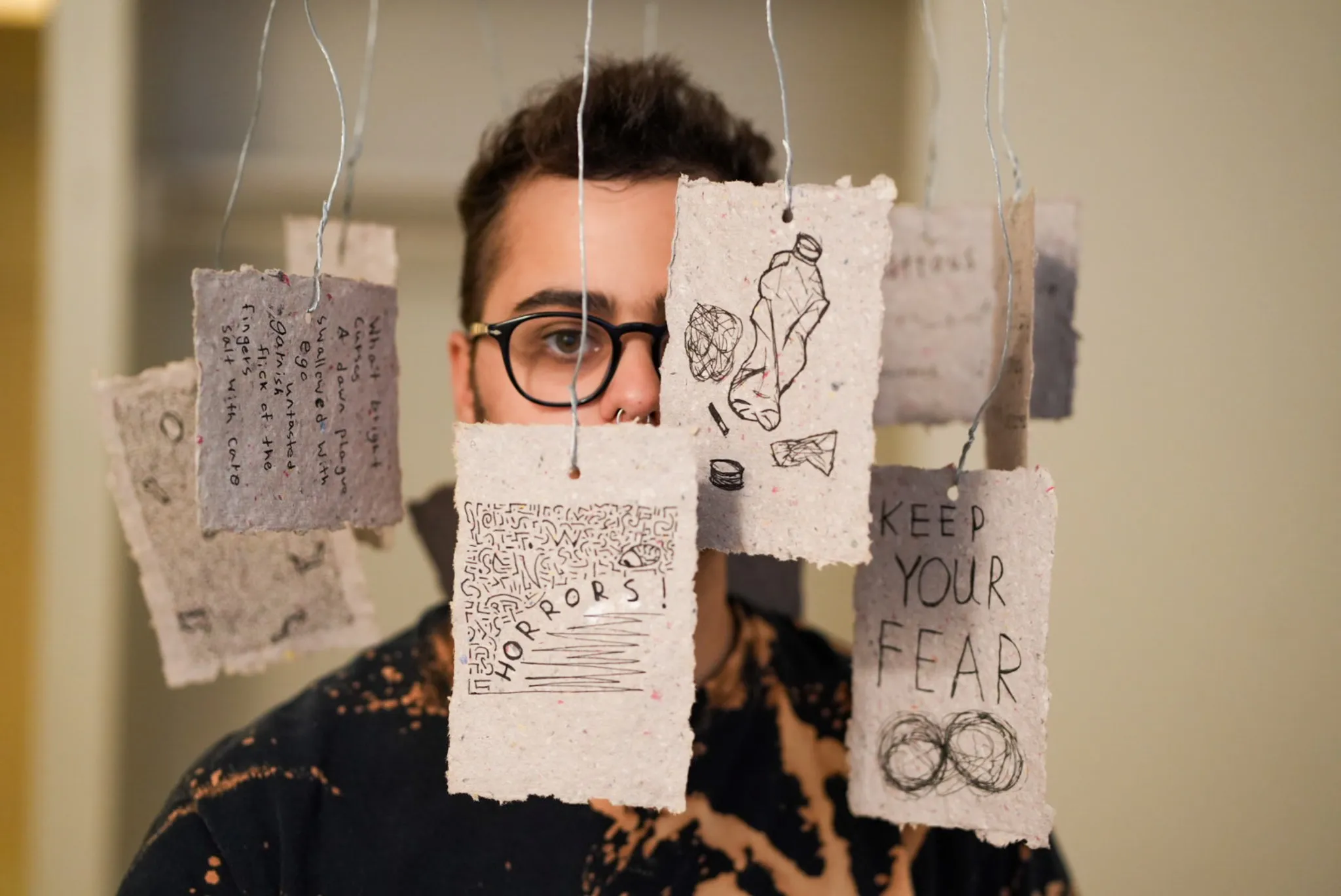

The exhibition, hosted at Art Access and running until Sept. 12, is laid out like a “life cycle” according to Westbrook. It begins with “Restless Night,” an interactive multimedia piece styled like a child’s mobile. Mantras affirming Westbrook’s monstrous identity hang from homemade paper next to bits of trash, comparing the many different ideas of what a monster is and asking how a younger Westbrook would cope with monstrousness.

“Having art allows me to calm down and sit in that emotion in a way I wouldn’t naturally let myself.”

“‘Restless Night’ was really exciting to me because there are so many ideas of what a monster is, and that starts at the youngest form: what does a child imagine a monster is?” Westbrook says. “I really liked this blending of harmless and very harmful versions of monsters… hopefully people will get to reflect and think about their childhood as they look through that.”

Next is a six page mini zine mimicking a dialogue with Westbrook’s younger self, asking a question that’s familiar to his ears: what would they tell their younger self? Westbrook has never known how to answer. “I am my childhood self’s monster and hero,” Westbrook writes in their artist statement. “I find moments where that younger version of me is afraid and is in awe and I explore my own fear and admiration towards her.”

The zines included in the exhibition are all free to take; Westbrook intentionally wanted to stay true to the accessible, DIY history of zines. Donations are accepted at the show, with 20 percent of artist proceeds benefiting the Trans Justice Funding Project.

“Split Hair” continues the Monstrous life cycle. Westbrook shaved her head for the first time for this piece, dumping their hair onto canvas and mixing with orange paint. He says shaving their head added another layer of vulnerability to the piece. “Even pre being on any kind of hormone therapy, I was always hairy, and there were always comments about that,” Westbrook says. “There was just so much control around my body… all of these feelings of constant, outside perspectives on what my body looked like.”

The depths of texture created when Westbrook then removed the hair challenge several important narratives of control: “There’s such a rich history of hair being a method to police marginalized folk,” they say. “There’s such a specific circumstance where hair belongs and anything outside of that is breaking the rules and deemed anywhere from a little bit gross to this horrible, monstrous, evil thing.”

Westbrook compared the painting’s final texture to scabs, also saying that the hair used in the making of the piece is on display in a bag next to the painting. “There’s a lot of expectations for paintings to be more flat on a canvas… getting to break that norm through a painting, through a frame, through a canvas, reflected me breaking the ones in my own body and the way that I present,” she says.

“There’s such a rich history of hair being a method to police marginalized folk.”

Westbrook says “Split Hair,” along with most of his pieces, is meant to make people uncomfortable but hopefully provide a safe enough place for attendees to question their discomfort. Westbrook describes watching people step back after viewing “Split Hair,” but at the same time lean forward to get a closer look. “A lot of these pieces are kind of gross. They’re made to make you feel a bit uncomfortable,” they say. “Everything I’m making is gross. To me it doesn’t feel sad but that’s frequently what outsiders will view it as — this sad, monstrous thing. To me, there is a holy glow to all of these pieces that feels so unrestricted.”

Grossness has become political in the wake of vitriolic arguments leveled against gender-affirming medical care. Pursuing gender–affirming surgery has been made into a monstrous decision, with particular negative attention directed towards scars. “I remember even the kindest of cis allies that I had were really stressed about me getting any form of gender-affirming surgery because surgery is scary and scars are something that turn a lot of people off,” Westbrook says. “To me, this feels like the most exciting and hopeful thing I’ve ever done and to you it’s a scary risk that you don’t think I should be taking.”

Westbrook’s series “What you call a mutilation, I call a feast” focuses on these different relationships to scars, presenting the audience with several questions: “Is the scar the wound or is it the bandage? … Am I locked here by this scar or am I free because of it?” For Westbrook, these questions exist within the larger context of harmful narratives surrounding top surgery in particular, where the word “mutilation” is often weaponized against folks seeking medical care.

The exhibition wraps with a behind-the-scenes short film and another zine. “Under Covers” has attendees enter a blanket fort to learn more about the making of this exhibition. “Growth,” a 16-page zine, explores what it means to be man-made through the lens of queerness and nature. “Personally, zines are a great way for me to get to interact with art while sidestepping a lot of my neurodivergent barriers,” Westbrook says. “I really love that it gets rid of a lot of perfectionism for me because when you go out and you find zines places, they’re photocopied, they’re blurry, they’re weird — none of it is intended to be perfect.”

Identity is everywhere in Monstrous, and Westbrook says he’s no longer willing to sanitize her monstrousness. “I’m trying to distance myself from being the ‘good’ or ‘nice’ trans person. I hopefully am not going to be like, a true asshole to people, but I do jokingly say I’m in my asshole era because I’m going to tell you what I want, I’m going to tell you what my needs are, I’m going to tell you my thoughts,” they say. “You can have a conversation with me: let’s negotiate, let’s figure out how we can work together … but I have no desire to cut away pieces of myself so that you accept me or are willing to interact with me.”

Westbrook describes a baby tiger crawling into their arms—something monstrous, but also small and delicate, something easy to abandon or kill. This art show has been a chance to explore being a monster in a way that’s protective, looking back and holding these parts of himself in a way that’s not possible outside of art.

“I have no desire to cut away pieces of myself so that you accept me or are willing to interact with me.”

“I think of it almost as an ache, of finally seeing the parts of yourself that you’re afraid of be shown,” Westbrook says. “I really hope that trans people enter this space and get to see parts of themself they’re still afraid of being held with love and care and being presented as like, these are artwork, these are worth spending time with, and I want to highlight them. I want them to be some of the first things you see and know about me. I’m really hoping it’s that ache of stretching a muscle that you didn’t know you had.”

Monstrous is open until Sept. 12 at Art Access. Westbrook says it’s important to them that the show is at Art Access, which works to increase accessibility to the arts through opportunities for disabled artists, and training for community and cultural organizations. Paintings are hung at specific heights to accommodate wheelchairs, and Westbrook also recorded audio descriptions of their work to ensure multiple avenues of engagement.

Stay connected with Westbrook as they pursue their next project—a documentary video series titled Acknowledgements, exploring the behind the scenes processes of local artists—by visiting their website lwestbrook.com and their Instagram, @lewisrllw. You can also purchase items from their shop, Salted Fruit.

Read more about local art exhibits:

Mestizo Arts Presents: Home Is Never Dead; It Isn’t Even Home

Lunares Explores the Unseen Power of Tears in Lágrimas: Rain, Glitter