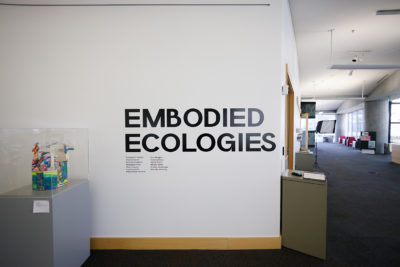

Embodied Ecologies: Where Disability Meets the Natural World

Art

The art in Embodied Ecologies—an exhibit and meditation on the ways that disability, health, and the environment intertwine—takes many forms: sculpture, painting, poetry and mixed-media. A film, flickering with the nostalgia of analog, layers footage of artists at work over blue-hued landscapes. The emotion in the gallery ranges from grief and despair to passion and euphoria. Colors span from the dull browns of anthropogenic decay to the brilliant pinks, yellows and greens of ecstatic nature.

Embodied Ecologies came to life through Natalie Slater, a graduate student in the University of Utah’s Environmental Humanities program, and Art Access Utah, a local organization working to increase accessibility in the arts. “It’s not a support group,” says Slater. “It’s different. We’re all coming together and doing this thing that we love, which is art, but we also have the shared experiences of non-normative bodies or health situations.”

“… we also have the shared experiences of non-normative bodies or health situations.”

A Mellon Foundation Scholar, Slater was tasked to facilitate an environmental justice initiative with a local organization. She discovered Art Access and met with Gabriella Huggins, the program’s executive director. Together, they came up with the idea for Embodied Ecologies and put out a call for artists to join their collaborative group.

The working group began meeting in February with six artists, Slater included, representing a wealth of different backgrounds and lived experiences. Together, they identified themes for the project, developed their ideas and collaborated on the gallery’s centerpiece, “Woven Lake.” Slater says, “We identified the key themes of kinship, water and weaving, and I think you can see those both in the medium choices and thematic choices of the pieces.”

“We identified the key themes of kinship, water and weaving, and I think you can see those both in the medium choices and thematic choices of the pieces.”

“Woven Lake”, the heart of Embodied Ecologies, features two wooden boards, one resting on top of the other. The lower, much larger board outlines the Great Salt Lake at its historically high levels of the ’80s. The dwindling shape above reflects levels today. The piece is a sobering reminder of Utah’s most pressing environmental challenge—the drying of the Great Salt Lake. Its rapid decline, due largely to climate change and population growth, threatens both the habitat and civilization of the Wasatch Front. As the lake shrinks, more and more of the arsenic at the lake bed will be exposed, threatening the health of all residents with what Joel Perry described for the New York Times as “an environmental nuclear bomb.”

Environmental inequity in Salt Lake City has existed since its inception. Historical redlining dating back to the 1880s divided the city along its rail line, leaving low-income workers to live west of the line, exposed to the railroad’s pollution and that of the heavily toxified Jordan River. Today, residents of the West Side are still much more vulnerable to the negative health effects of industrialization, which can be linked to disability.

“As the lake shrinks, more and more of the arsenic at the lake bed will be exposed, threatening the health of all residents with what Joel Perry described for the New York Times as “an environmental nuclear bomb.”

“Something interesting about disability is that it’s inextricable from other identity factors, such as race, class and gender,” says Slater. “This is true in regards to both the perception and distribution of disability. Early definitions of disability were based on capacity to work. At the same time, structural inequities may force people into disabling labor conditions.”

The artist statement for “Woven Lake” reads that its entanglement of disparate mediums “symbolizes the importance of community care in the face of both ableist structures and environmental health challenges, such as the drying of the Great Salt Lake.” Each medium ties the work to a contributing artist and binds them to each other.

There’s grass, a nod to Evangeline Amadu’s three-dimensional canvas painting of Antelope Island ecology, “What Happens at the Marsh at Dusk.” There’s knit fabric and bookbinding thread, representing Stephanie Choi’s poetic rumination on life with scoliosis (“Spine: Rematerialized”). Coconut husk and Sāmoan tapa cloth reflect Mālia Malae-Godinet’s “Disposable Vā,” contrasting the West’s emphasis on eliminating plastic waste with its disdain for Pacific Islander communities suffering the effects of climate change. Buckskin and beads tie to Victoria Meza’s piece, “Building Community,” her art style inspired by Plains Tribes of the 19th century. An 8mm analog film by Slater and Stan Clawson alludes to the “Embodied Ecologies” video and homemade paper references Michelle Wentling’s woven “Cuyahoga Impression.”

“Something interesting about disability is that it’s really inextricable from other identity factors.”

Eight additional artists contributed to the exhibit, joining the project over the summer and developing more pieces that aligned with the themes and the idea of disability’s intersection with nature. The working group, says Slater, was resilient and adaptable when unexpected problems arose, such as surgeries or illnesses. Deadlines and meeting times were flexible. People were kind and understanding of the individual needs of each member. “The amount of gentleness and empathy that I’ve experienced in this group has been especially meaningful to me,” says Slater.

Resilience. Adaptation. Gentleness. Empathy. Each is a key tenet of addressing public health and environmental issues in a way that serves everyone. That’s Slater’s ultimate goal—opening up more conversations about the intersection of disability and environmental equity. “There’s a lot to learn from how disabled communities have facilitated care and facilitated survival in systems that aren’t made for them,” says Slater. “There are things to gain from looking at this intersection.”

“There’s a lot to learn from how disabled communities have facilitated care and facilitated survival in systems that aren’t made for them.”

Historically, people with disabilities are often ignored in communications surrounding climate change and who bears the brunt of its effects. But in Salt Lake City, health is at the forefront of our climate struggle, meaning lawmakers may finally start to listen. “Because so many of our environmental issues are related to health here with the Great Salt Lake, I think [we have] a good opportunity to directly bring in these communities,” says Slater. “Being more mindful about how people’s health is influenced by their environment … essential component of addressing climate change.”

You can visit Embodied Ecologies on the fourth floor of the Salt Lake Public Library through November 11. After that, it moves to the Digital Matters space at the Marriott Library on the University of Utah campus, where it will stay for two more weeks. To learn more about Art Access Utah, check out their website at artaccessutah.org.

Read more on local art exhibits:

Showcasing the Brightest in Utah Furniture and Interior Design: The 2022 Utah Design Exhibit

Art As Wellness: UMOCA’s See Me Exhibit