Images of Trust: Maru Quevedo

Art

Self-taught photographer Maru Quevedo began making art as a teen in Buenos Aires, Argentina. A mostly black-and-white film photographer, Quevedo’s portraiture work and street photography reflect her desire for connection. “Everything that I’ve had a chance to work on or be a part of is because there’s been trust built,” says Quevedo. “I think my personality wants more of the connection first until I can go shoot and be comfortable behind the lens with that exchange. That takes time.”

One of the most striking recent images on Quevedo’s Instagram is a black-and-white photo of a person carrying a bag, arms up and bag slung down the nape as though the bag has become heavy. Behind them is a dress store, and you can just make out the glitter of sequins behind the mannequins. This was taken in Los Angeles, where Quevedo has been attending the Los Angeles Center of Photography (LACP). “Many times [with] the locations they asked me to go to, I will go one time, two times [or] three times, and I would not take one photo,” says Quevedo. “I would much rather go and walk for hours until people would see me and start feeling comfy versus just go[ing], snap[ping] a photo and leav[ing].”

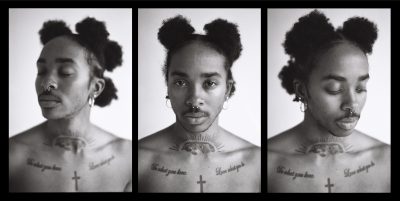

Her work is warm with care and selfhood, elevating images to their best, offering faint windows into their creator. I think about this when looking at Quevedo’s portraiture work with Jordan Danielle from last year. Danielle’s gaze communicates a sense of Danielle that is embedded in their connection and trust with Quevedo. To be snapped by Quevedo is to have earned this mutuality.

Quevedo has been busy in Salt Lake. Since moving here from Argentina in 2014 and dealing with a frustrating visa process, she’s made connections in Salt Lake’s bustling art and queer scenes, growing in their subcultures’ political activism, dance and following one project after another. “Everyone is willing to teach their craft,” says Quevedo, “from drawing nights with incredible, talented muralists in the city to … people doing volunteer work.”

In 2020, Quevedo fell in with Local Propagandists, a screenprinting collective in SLC whose work has populated the signs in protesters hands and become iconic symbols of the widespread call for local and systemic justice, especially as that art began to populate our homes, lawns and cars post-protests—to Quevedo, this was an indispensable time. Agitation work put her in tough dialogue with people who she would come to embrace as family. “[We were] having conversations of what was happening and how we were gonna present it in art, or how we were all feeling that we were screenprinting messages that were pretty strong. It was a way of processing what was happening,” says Quevedo. “I think it was a personal process for each of us and also a way to give back to the community in the shape of art.”

For Salt Lake, 2020 was a learning opportunity. We had all seen mild protests and marches before; we had never seen a police car catch fire before. “Proximity to politics is a lot higher in Argentina,” says Quevedo, who attended the University of Buenos Aires and studied sociology with a gender studies emphasis. Making art with her friends and experiencing a much more politicized university environment, Quevedo had photographed conflict and protest before. 2020 in Salt Lake was a time to help others think more on the act of documentation. “I think it was an interesting time to practice compassion,” she says. “I want to believe that nobody had bad intentions on capitalizing their photography work through social struggle, but I think those conversations were brought up from the communities that I was from: How are we presenting, what is it we’re saying and how [are] we fail[ing].”

This insight was not born recently, and the evidence lies in her work. Beyond a long history of artmaking as a teen in Argentina, Quevedo has created images that stick with you, whether capturing a quiet moment or a sweet embrace, a pretty fern or someone’s ass hanging out. If they look like they belong on Instagram, it’s because they do. Quevedo captures the things she feels connected to—that means people, places and moments that may be taken for granted. These images are banal and lovely, both playing right into and resisting the monotony of Instagram. There’s a wonderful quality about Quevedo that feels resilient to category.

This feels like a consequence of how she thinks about documenting the world. “I don’t think I’m in any place to say what’s ethical and what’s not,” Quevedo says. “You have super–well known photographers who have done work that is very in-your-face, very pushy … then you have others who have built those relationships, [who] talk through their story and understand what they wanna see. At the very end of that process they snap a photo.” Quevedo’s images are the result of that kind of rigor, the boots-on-the-ground giving a shit.

“I feel like now I’m at a point that I have the chance to start creating my own projects,” Quevedo says. “Am I a photographer? I love to document. My camera has been the tool to express myself. It’s been like this for a long time.” Check out Maru Quevedo’s work on Instagram @maruquevedo.

Read more about Local Propagandists:

Art for Abolition: Local Propagandists