A Ringing Sound: The Jesus and Mary Chain on Psychocandy

Music Interviews

“We just wanted to make a record that had all the ingredients, really,” says Jim. Drawing influence from a diverse range of artists— from The Velvet Underground and The Shangri-Las to Ramones and Suicide— the Mary Chain grafted noise elements to pop music in ways that both reinforced a heritage of innovative bands and exalted the group as the harbingers of a musical upheaval. “I’ve always been attracted to noise in pop music,” Jim says. “[On Psychocandy], we worked in all of the elements—noise music, pop music.”

Thirty years on, listening to Psychocandy still elicits the same rush of youthful, amphetamine-dripping energy that it did upon its release in 1985. From the iconic opening of “Just Like Honey” to the Beach Boys–freak-out–turned–fright-pop “Never Understand” and the whirring wall of sound on “You Trip Me Up,” Psychocandy is one of the most thrilling albums ever put to record.

But for a group whose rise to infamy was about as quick as a three-minute pop song, the Mary Chain’s formation was, for a long while, nothing short of sluggish. “We had a pretty dead-end existence,” says Jim of his and his brother William’s upbringing in the Scottish “new town” of East Kilbride, a suburb of Glasgow. “If you’re into music— which we were—everybody kind of fantasizes, ‘Well, wouldn’t it be great to be in a band, be a rock star?’”

Isolated from the hullabaloo of London, the Reid brothers soaked up a kaleidoscope of musical inspiration that was accessible to them from an early age. “We bought a record player,” Jim says, “but we had no records, so we borrowed a bunch of stuff, which was, as I recall, a big bunch of Beatles albums and Bob Dylan.” They quickly immersed themselves in the playful scene of glam rock that swept through the UK, absorbing influences such as T. Rex and David Bowie. When the Sex Pistols commandeered the nation’s consciousness in the late ’70s, “that’s when the idea of being in a band really formulated,” Jim says. “Until punk came along, it seemed like more of a fantasy than a reality.”

By 1983, the Reid brothers finally committed to forming a band. “We just got fed up with complaining about why music was so bad,” Jim says. “We thought, ‘Well, fuck it—if nobody else is doing it, we’ll do it.’” Though there were contemporaries that they looked to—Echo & the Bunnymen, Cocteau Twins, The Birthday Party and Einstürzende Neubauten—the brothers felt disillusioned by how the punk movement had progressed. “The fact of the matter is that most of what we were hearing was just dreadful to us,” he says. “It seemed to us that the whole excitement of what had happened during punk had just fizzled out—it’d gone away.” They were especially irritated by the inundation of the NME and Melody Maker by irksome new wave groups. “We just wanted to shake things up a bit,” he says.

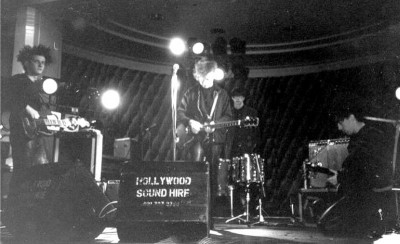

“Suddenly, the band was happening. We needed stuff to rehearse, so we started writing songs.” The brothers bought a Portastudio—a four-track recorder—and began writing tracks and recording demos of them. Unable to get a gig in Glasgow, the brothers, joined by Douglas Hart on bass and Murray Dalglish on drums, traveled to London to play their first show, at Alan McGee’s venue, The Living Room.

McGee was tipped off to the group by Bobby Gillespie, frontman for fellow Scottish group Primal Scream, who ended up joining the group later, in 1984. “I heard them and really liked them, so I just said, ‘Come down [to London],’” says McGee about how he first encountered the Mary Chain. They played mostly covers, such as Syd Barrett’s “Vegetable Man,” Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love” and the Subway Sect’s “Ambition,” and, though the Reids had one of their trademark arguments, McGee was thoroughly impressed. “We signed with ’em there and then,” he says. McGee’s label, Creation Records, would release the group’s first single, “Upside Down,” in 1984.