Bury My Heart in a Record Sleeve

Music Interviews

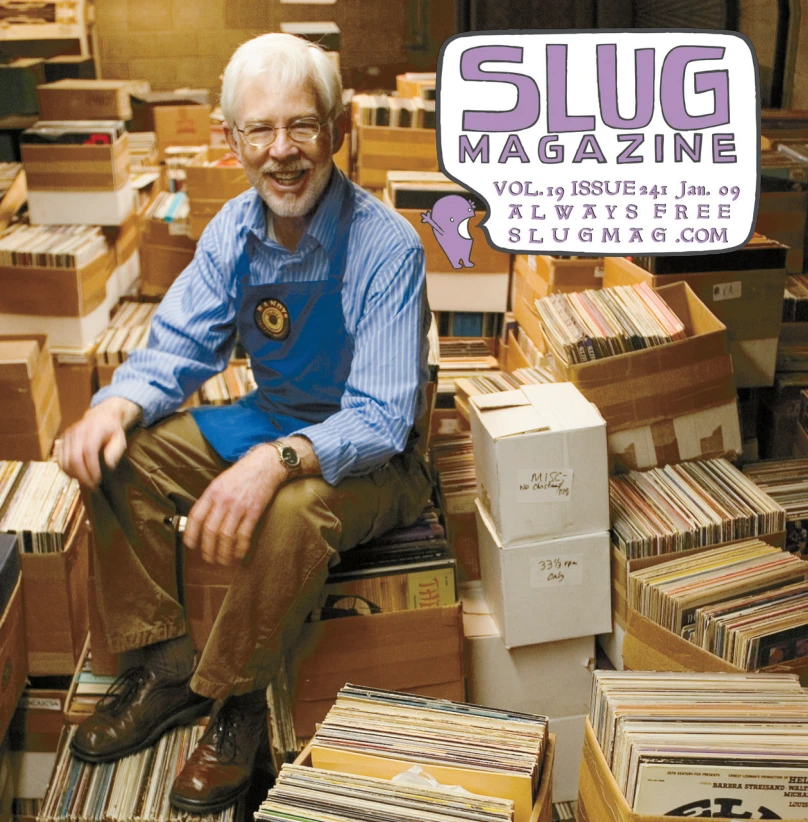

2008 marked Randy’s Records of Salt Lake City’s 30th Anniversary. This is quite a feat considering that every record store that was open in 1978 is now closed or no longer sells records. Cosmic Aeroplane, Raunch and Smokey’s have long since gone the way of the eight-track. Randy’s persevered through the late 80s and early 90s, when people ditched their record collections for shiny new CDs. Now we are in the new millennium, where iPods and digital downloads have virtually wiped out music sales. Randy’s is a monument to the preservation of vinyl and the warm sound that jumps out of the grooves. A sound that is still superior to any version digitalia has yet offered up.

RS: I still have the first record I bought, in 1959. It’s pretty cool that I’ve somehow managed to save it, even though I ended up in Vietnam and everything. It’s Santo and Johnny’s Sleepwalk from 1959.

SLUG: The LP?

RS: It is a 45––I couldn’t afford albums back then. Somebody gave me a record before that in ‘58 or ‘59. I didn’t have a record player, so I took a piece of paper and made a cone out of it and stuck a pin through it––like a megaphone––and stuck it down on the record. Luckily it was free, an old Eddy Arnold record. I got something that would spin and tried to get it spinning at the right speed. That’s what got me into records, the music coming out of the grooves. That’s why I bought a record player and my first record, Santo and Johnny. I started getting records from jukebox places. That’s almost where all of my records were from, 45s that came off jukeboxes.

SLUG: Were there record stores back then, or would you buy most of your records at Woolworth’s?

RS: Yeah, Woolworth’s is one of the places I went––they had a pretty good little record department. Broadway Music was around, House of Music on Main St. There were several stores where you could buy 45s. I couldn’t afford those very often, and I usually waited until they came off of jukeboxes. They made 45s hot for jukeboxes like the Rolling Stones. They would turn up so loud it distorted, so that it would be louder than everything else on the jukebox.

SLUG: What else was going on in your life at that time?

RS: I went to Vietnam in ’67 to ’69. I had most of my good records shipped over from the U.S. I was the only guy in this place, called Long Bin Post, that had a really good sound system and I remember my brother sending me The Beatles’ White Album. I’m pretty sure I was the first person to have that. We had people come from all over the base to listen to it, including officers. I was a regular non-commissioned person and it seemed like the ranks didn’t matter. I built a strobe light. I made a wheel with a spot in it for light to go through. I took a fan off of a portable air fan and could turn it up and down, with the light shining through at the right speed. It mimicked a strobe light pretty well.

SLUG: Randy’s little disco going on. RS: Yeah, I must have had 200-300 albums over there. We’d play stuff like Jimi Hendrix and The Beatles. What happened after Vietnam?

RS: I was going to quit collecting records. I had a job that I didn’t like as a typesetter for 10 years and got tired of that. Some of my friends worked at a place called ABC Record and Tapes, it was one of the record labels and was also in distribution. One guy wrote an article about my record collection and said it was like letting a pyromaniac loose in a match factory––it turned out to be true. I started buying records again, getting a little bit more into albums.

SLUG: What kind of stuff were you listening to then?

RS: I listened to everything. I like doo-wop stuff like The Penguins “Earth Angel,” The Flamingoes I Only Have Eyes for You. I like the sound of the old doo-wop, because that’s what I grew up with. Whatever you grew up with probably works for you. It does something to our brains. After Vietnam I lived next to West High School in a two-story house for about three years. A friend of mine, Ken Meyer, was an engineer for KRST and he set up a little transmitter and set it to a certain frequency. It wasn’t powerful, just enough to reach the Board of Education buildings and parking lot. People would come up to my door to request songs. Then I had this idea to take this into a lounge (or bar) and pipe the music in. It would be easier than hauling 10,000 records into a bar. There were two bartenders from Jerry’s Brown Bag––Fred Ekin and Dick Wilson––that loved the idea. Jerry said, “Nobody’s gonna like that old stuff.” The other guys thought people would and bought a place called The Bongo Lounge. The first thing they did was get it hooked up and we started playing music from my house one or two nights a week. By then it was over the phone lines.

SLUG: That’s pretty great, that’s pre-pod casting.

RS: We did that from ’72 to ‘80 and I finally quit. I had opened up the shop in ’78 and it was taking all of my time. When I got back from Vietnam I had duplicates of records I would sell for 50 cents each. I remember Salt Lake City by the Beach Boys selling for 50 cents. Those records are worth $200 now. I saw the Beach Boys in 1965 on State St. I just happened to be downtown and they were in this convertible driving down State St. and throwing 45s out to people. I wanted to open a record store on Gerard Avenue in a three-story house with three apartments, but it turned out to be no longer zoned for business. I was stuck with that and I just kept the dream alive until 1978, when I finally opened up this store.

SLUG: You’ve been at this very location?

RS: 30 years, yeah.

SLUG: You’ve seen this neighborhood go through a lot of changes. All of the record stores that were open when you started are no longer in business.

SLUG: You’ve seen this neighborhood go through a lot of changes. All of the record stores that were open when you started are no longer in business.

RS: The only one I can remember now that started at the same time is Recycle Records on State St. A fellow that used to work for us, Dean Chadburn, bought it from the original owner.

SLUG: He doesn’t even sell records anymore.

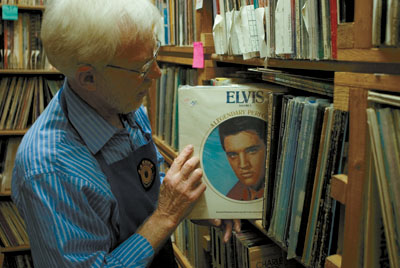

RS: That’s true. The business goes up and down. The late 80s and early 90s were really tough. I was in debt and I decided that I had to sell my personal records. The whole reason I went into business was to build up my collection and I had to sell my best records. Stuff like The Flamingoes, The Spiders, The Swans, The Du-Tones––there were so many, I don’t remember now.

SLUG: You had the original imprint of all of these?

RS: I did and those are the most collectible. Those are the ones I had to sell. It was at about this point that Randy and I got into a lengthy discussion about the virtue of vinyl analog sound vs. digital. Randy quotes at length from an article, by Neil Young titled “The Darkness of the Digital Age.” One Young quote pretty much sums it up, “Digital is a disaster.”

RS: The article says: “Your brain is capable of taking on an incredible amount of information, and the beauty of music is like water washing over you. But digital is like ice cubes washing over you––it’s not the same.” A friend of mine recently told me it was called headroom. I call it soundstage, like if you close your eyes and listen to a record, you can almost imagine the room they were in on a good recording.

RS: The article says: “Your brain is capable of taking on an incredible amount of information, and the beauty of music is like water washing over you. But digital is like ice cubes washing over you––it’s not the same.” A friend of mine recently told me it was called headroom. I call it soundstage, like if you close your eyes and listen to a record, you can almost imagine the room they were in on a good recording.

SLUG: Some of the records I think exemplifies this best are the Alfred Alpeka albums like Taboo, that he recorded in the late 50s early 60s. They used state of the art recording techniques and recorded in a large dome.

RS: Classical is that way and a lot of Jazz, because they didn’t use too many microphones. CDs sounded really bad in the early 90s, because they put a microphone on everything. The engineers would sit back and say, “Let’s turn this one down and this one up,” but you would lose that synergy. When they would use only two or three microphones, you could hear everything going on. It bounces off the walls and comes back and gives you harmonics. You can almost picture being there, where they were recording. I challenge people to listen to a good record on a good system and listen for the music rather than the noise. I think there are two camps of people out there, the ones who listen to music, and the ones that listen for noise and distortion. If you’re listening for noise, you are going to hear noise on a record, but if you focus on music, that’s where the beauty, realism and fun come out. It’s fun to play records for me. Instead of listening to the sterility of a CD, listen to the richness of vinyl, the beauty that is in the grooves.

It was a pleasure to sit down and talk to someone who knows so much about records. Randy Stinson is a virtual library of information about how to grade and sell them. He even retouches covers with magic markers. He has tried to pass along to his knowledge children, but it is possible we may lose his expertise someday. There is currently no heir poised to take the reins of the analog age and ride that chariot into the future. Stinson is at an age where retirement is closing in on him. Possessing a clear mind, able bodied and near 70, Randy will continue to do what he loves even though retirement seems tempting. Anyone who wants to live the dream can make him an offer. Salt Lake City just wouldn’t be the same without Randy’s Records.

Randy’s Records is located at 157 E 900 S and is open and ready for your business Tues.- Fri. 10 a.m.-7 p.m. and Sat. 10 a.m.-6 p.m.